Sometimes the justice system gets it wrong, but that doesn’t end all hope of eventually making things right.

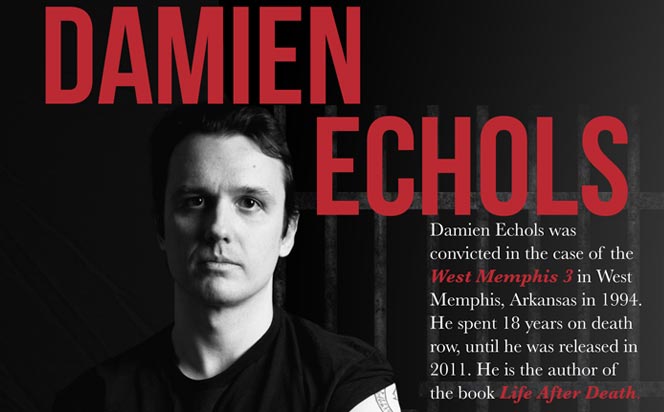

In the case of Damien Echols, the notoriety of perceived guilt is rivaled only by the attention shone upon reprieve. After 18 years on death row as one of the “West Memphis Three,” Echols is now free, and an author. He will tell his story at 7 p.m. Monday, April 22, in Cline Library Auditorium on the Northern Arizona University campus. The presentation is free and open to the public.

Another story will be told much more quietly in June, when Jason Krause, supported by the Arizona Innocence Project, will see his opportunity for exoneration unfold at an evidentiary hearing.

The two cases are tied only by themes of delayed justice and the power of unrelenting advocacy.

Rober Schehr, professor in NAU’s Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, is familiar with both themes as executive director of the Arizona Innocence Project. His students have worked numerous cases over the years motivated by a passion for overturning wrongful convictions and see the Krause case as winnable.

“This will be our first exoneration if we win,” Schehr said. “It looks like the evidence is lining up. This is the most promising case we’ve ever had.”

In cases such as that of Echols, advocates have seen the tide turn against questionable evidence, shoddy investigations and quick public condemnation.

In 1994, Echols was one of three teenagers convicted in the murders of three boys in West Memphis, Ark. The case drew widespread attention, then scrutiny, and in 2011 all three were released in a plea deal.

Echols, infamous for being convicted and famous since his release, has written Life After Death to depict part of his personal journey through the criminal system. And it is far from over. Echols still seeks full exoneration through DNA testing, his release having come from an Alford plea that neither conceded guilt nor established his innocence.

The journey for Krause also continues. He, too, is free, having served more than 10 years in prison for a 1996 conviction for manslaughter in Yavapai County. Serious doubts have arisen about the comparative bullet lead analysis used in the case—a process no longer used by the FBI because of its fallibility.

“We’ve been working on this case going on four years,” Schehr said. The case came to NAU from the FBI once the bureau realized it couldn’t stand behind hundreds of troublesome cases based on the faulty analysis. Krause’s was one of them.

The process has involved a complete reanalysis of the case, interviewing witnesses and reconstructing the crime scene. Expert witnesses scheduled to testify in June will cost $15,000—money that the Arizona Innocence Project must raise.

Schehr hopes that events such as the Echols presentation will raise awareness of his group’s work and its reliance on private donations to supplement Federal grants.

“We want to expose people to the issues,” Schehr said. The Echols presentation is free, he said, because “we don’t want people to feel inhibited about not being able to afford it. We would rather pull from a broad swath of the community.”

Echols will be available to sign copies of his book after his presentation, which is scheduled to conclude at 8 p.m.