At 10 years old, Mariah Letowt found her calling while visiting her great-grandmother in a senior community.

It’s an odd place to do that when one’s calling is working with birds.

Letowt, a senior at Northern Arizona University who studies environmental science and is a member of the Honors College, studies how birds talk to each other. On that long-ago day, she just happened to visit when the founder of Forever Wild, an avian sanctuary in Tucson, brought a Harris’s hawk to the senior home to do a demonstration for residents. She’d always been interested in wildlife and dinosaurs, and she immediately fell in love with the majestic predator. After the demonstration, she introduced herself to the bird’s handler.

Working with baby birds at Forever Wild, her interests shifted from raptor to raptor—instead of becoming a paleontologist and studying dinosaur fossils, as she’d planned, Letowt realized she wanted to work with birds. As a high school senior, she enrolled in a course through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that taught students how to identify birds based on the species’ vocalizations. This interest led her to NAU, which offered opportunities to do research in wildlife biology, ecology and natural resources management.

And Letowt has made good use of the research opportunities available to her. As a freshman, she jumped into undergraduate research, working as a field assistant with then-doctoral student Rabecca Lausch and Tad Theimer, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, working on Lausch’s flicker project.

“Mariah helped Becky lug her sound recording equipment around the desert for a spring and summer, tracking down Gilded Flickers and playing songs to them and noting their behaviors,” Theimer said.

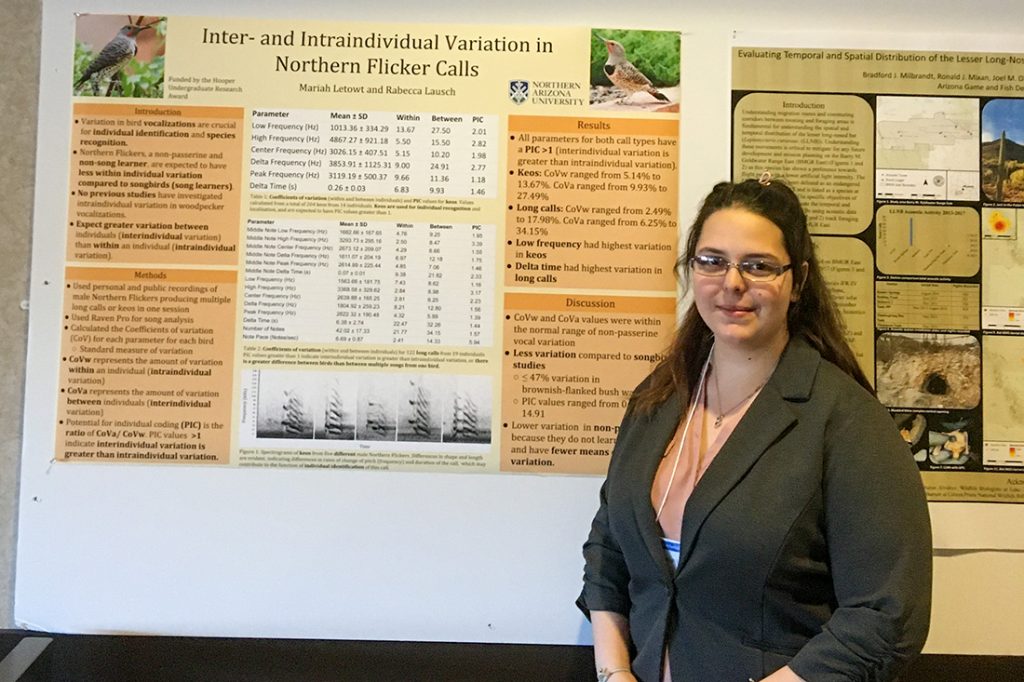

Letowt then developed a proposal to study the vocalizations of the Northern Flicker, a vocal non-learning type of woodpecker, for which she received a Hooper Undergraduate Research Award (HURA). Flickers, whose songs are innate, present something of a mystery to researchers when it comes to where their songs come from.

Vocal learners like songbirds, parrots and hummingbirds learn and practice their song from listening to their parents, while vocal non-learners, which comprises most other birds, rely on their genetic code to determine their song. Most research focuses on vocal learners, which left a dramatic knowledge gap in the possibility of vocal on-learners. Letowt closed that gap a bit with her study of the Northern Flicker.

The flicker’s songs are individually distinctive, which allowed Letowt to expand survey methods to include autonomous recording devices to determine how many flickers may be in a given area. To complete the research, she went into the field before sunrise to record wild flickers around Flagstaff, and she used recordings from throughout North America to look at geographic variations. Letowt was the first author on a paper accepted by the Wilson Journal of Ornithology.

Letowt is working on a second HURA-funded project that focuses on nine different species of New World cuckoos and how their vocalizations could result in an evolutionary tree. Her preliminary analysis shows that the groupings of species based on song analysis is different from an evolutionary tree made from genetics.

“This indicates that environmental factors could be having a bigger impact on New World cuckoo vocalizations rather than just genetics,” she said.

Theimer, who also is advising on this project, said he and Letowt discussed whether song differences reflected genetic differences in these birds, which led to Letowt’s analysis of publicly available bird songs from North and South America to determine how similar the songs were to each other and whether they grouped as researchers expected based on genetic relatedness.

“We found that in some cases they did, but there were surprises as well,” Theimer said. “For example, one species sang a very different song than his relatives, suggesting that there may be interesting ecological or social factors at work to bring about such a big difference.”

She’s kept busy during the summer with research as well. Last year she worked for the Arlington Ecological Service Office in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service studying the songs of black-capped vireos, which were previously endangered but delisted in 2016. From her desk in Arizona, Letowt used a limited energy detector to detect vireo songs and calls in autonomous recordings. And in between her HURA research, she worked with Bret Pasch studying vocal mice and other small rodents.

She’s indefatigable, Theimer said—excelling in all her classes, serving as president of NAU’s chapter of The Wildlife Society, helping put on the Astronomy Club’s star parties and growing plants for the Botany Club, all while staying on top of her research. And that’s not even what stands out most about this young researcher.

“Mariah is courageous,” he said. “She is a very shy person, and standing up in front of my lab group or the folks at a meeting and talking about herself and her work is extremely difficult. But every time, she pulled off the presentation flawlessly, with not a hint of nervousness. To face your fears and overcome them, and to do so with such excellence, is something we can all admire, and it was an attribute of Mariah’s that I found truly inspirational.”

Letowt is presenting once more before she graduates from NAU with yet another accomplishment—a 2021 Gold Axe winner—on her resume. She’ll share her cuckoo research at the Undergraduate Expo next week. After graduation, Letowt is moving to Haines, Alaska, for an internship with the American Bald Eagle Foundation, after which she hopes to be an ornithologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Eventually, she wants to get a Ph.D. studying bird song and avian communication. She’s especially interested in the evolution of bird song from dinosaurs to the birds of today.

Learn more about the Symposium and Expo, including how community members can participate.

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu