Editor’s note: This year, three NAU students were selected for the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and The NAU Review is profiling each of them this spring. Read about Laura Lee, another GRFP student, here.

Purple martins may be thriving in the eastern United States, but they’re struggling in the west. That worries Victoria Wiley.

The avid birder and NAU Ph.D. student explained that there are millions of the small, dark and iridescent songbirds living between the Midwest and the East Coast. As a result, they’ve been easy to spot and easy to study. Expert and amateur birders alike know their songs and mannerisms by heart, and scientists have been able to find out when and where the birds fly in winter.

Here in the Southwest, on the other hand, a desert subspecies of the purple martin is in danger of slipping into obscurity.

“The estimate is that there are about 5,900 desert purple martins in total,” Wiley said. “We know that they nest in the Sonoran Desert in Southern Arizona and Baja California. Other than that, very little is known about their migration route and natural history.”

Then there’s the matter of their choice of nest: the cavities inside large cacti.

“The fact that they nest in saguaro cacti is concerning, because with the increase in wildfires, the saguaro population is being decimated,” Wiley said. “They take 200 years to grow to the point where birds can nest in them. If there aren’t enough cacti to nest in, will purple martins go somewhere else, or will the population become even smaller?”

Thanks to Wiley’s research, we may never need to find out. The second-year doctoral student in population biology just received a prestigious fellowship from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP) to investigate whether the desert purple martin is actually its own species separate from its eastern counterpart. If she can prove it is, it could help secure federal protected status for the rare birds.

Wiley is one of three NAU graduate students to receive a fellowship from the GRFP this year. Awarded to just 2,000 master’s and Ph.D. students across the nation annually, the fellowship supports graduate research on important topics in the natural, social and engineering sciences.

“I feel so grateful to have the support of this fellowship,” Wiley said. “We live in an exciting time with access to international collaborations and innovative conservation tools. I look forward to seeing what the next 20 years look like in wildlife conservation.”

Wiley never gave much thought to birds until she took a fateful zoology class as an undergraduate at NAU.

“The professor happened to be interested in birds, and on Fridays, we’d go for bird walks,” Wiley said. Birding quickly became a hobby for Wiley, then an obsession: “After I graduated, I was working in labs during the weekdays and birdwatching on all my afternoons and weekends off.”

For a few years, Wiley stayed focused on molecular biology, working in lab settings in Salt Lake City and San Diego.

“I liked the structure of lab work, and I was always learning so much that I didn’t get bored,” Wiley said. “But I started thinking more and more about birds—all I wanted to do was go birdwatching. I thought, ‘Could I do that for a job? Would that take all the fun out of it?’”

Wiley decided to take the leap and find out. After reaching out to multiple Ph.D. programs across the country, she was thrilled to land right back where she’d started her college career: at NAU, where professor of biological sciences Loren Buck was looking for fellow bird-obsessed scientists to study purple martins in the Southwest.

As part of Buck’s lab, Wiley recently traveled to southern Arizona to temporarily capture a handful of desert purple martins. She fit them with tiny GPS-tracking backpacks in an attempt to discover where they migrate in the winter. When the martins returned to their desert breeding grounds in spring, Wiley analyzed data from one tracker and found that at least some of the birds spent time in northeastern Brazil.

“We know about the environmental threats desert purple martins face on their breeding grounds, but we need more information about environmental threats in their non-breeding grounds to implement protection across their entire range,” she said. “Their potential wintering range in northeastern Brazil is known to have elevated mercury levels in the water due to illegal gold mining and hydroelectric dams that have been constructed there.”

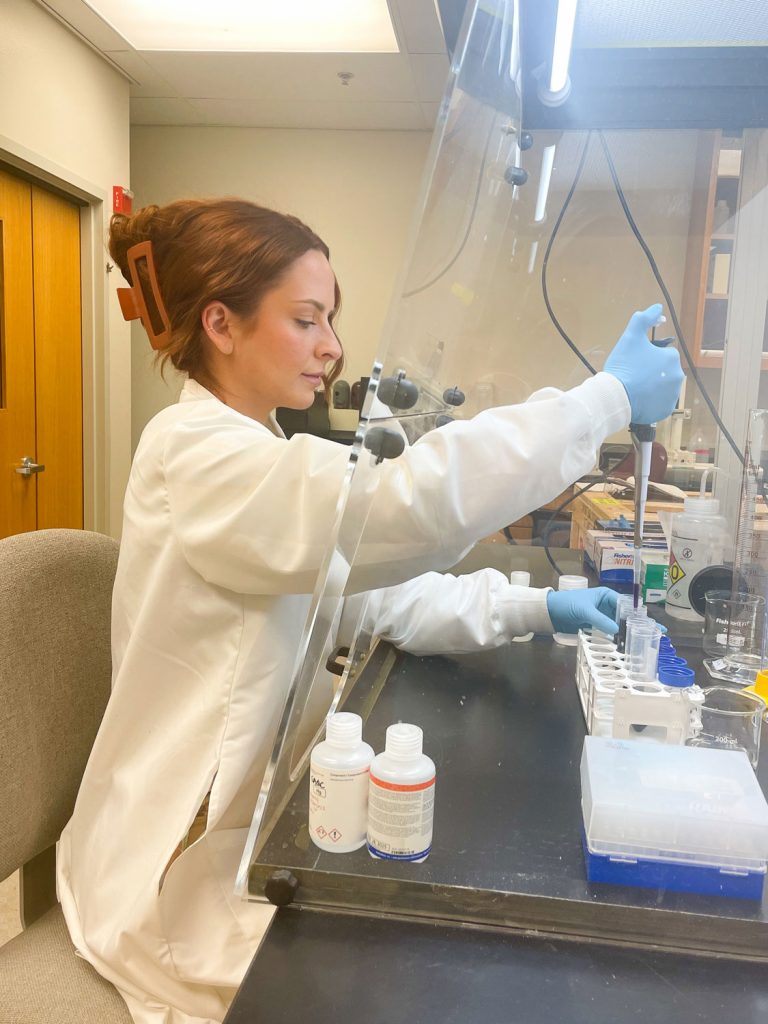

Wiley’s next step is to test the birds’ tail feathers for elevated mercury exposure. She’s also using feathers to sequence the desert purple martin’s genome, which could uncover genetic differences with the eastern purple martin.

Proving that the desert purple martin has evolved differently than the eastern purple martin could earn the birds special recognition as a threatened species, Wiley said.

“Because of their large eastern population, purple martins are considered a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature,” Wiley said. “If this subspecies were found to be evolutionarily divergent, they could be elevated to threatened, endangered or vulnerable status. That unlocks a lot more information on threats in their environment, a lot more funding for research and a lot more guidance on how to manage the small population.”

It’s bigger than birds

But the impact of Wiley’s research extends beyond one desert bird.

For one thing, desert purple martins are far from the only species that faces harm from mercury exposure. Wiley explained that opening the door to more research on the effects of purple martins’ potential elevated mercury levels could help demonstrate how mercury is threatening a wide variety of plants, animals and humans.

Plus, she said purple martins are long-distance migratory insectivores, like so many other threatened bird species.

“What that means is, they migrate from North America to South America and subsist on insects along the way,” she said. “This work could have huge implications for other birds that exclusively eat insects. That’s a big deal, because insectivores are considered one of the fastest declining foraging guilds of birds.”

Wiley loves that she can study something so niche and still make a positive contribution to wildlife preservation. That’s why she aims to find a career in the conservation field, perhaps one where she can continue experimenting with innovative tracking and sequencing technology.

“This work is bigger than me, and it’s bigger than birds,” Wiley said. “What’s so great about the scientific world is that all of these new field methods and lab methods get published and shared among researchers, opening the door for other people to continue adding knowledge. We all have different goals, but ultimately, we’re working together to maintain biodiversity and resources for future generations.”

Interested in applying for a grant or fellowship? Check out the Writing a Fellowship Proposal class; many students have won GRFPs, NASA grants and other major awards after taking the course.

Jill Kimball | NAU Communications

(928) 523-2282 | jill.kimball@nau.edu