Before Flagstaff’s lumberjacks were dedicated scholars, fighting athletes and fans of all things blue and gold, they were burly woodsmen traversing the nation’s largest ponderosa pine forest in search of valuable timber.

Since the early 1850s, the region’s prosperous, diverse arboreal features have fed into the creation and growth of a thriving logging industry, with intricate threads tying it to communities across the general Flagstaff area. NAU’s School of Forestry, created to address the rising demand for ecologists knowledgeable about timber management 100 years later, remains a critical piece of that story.

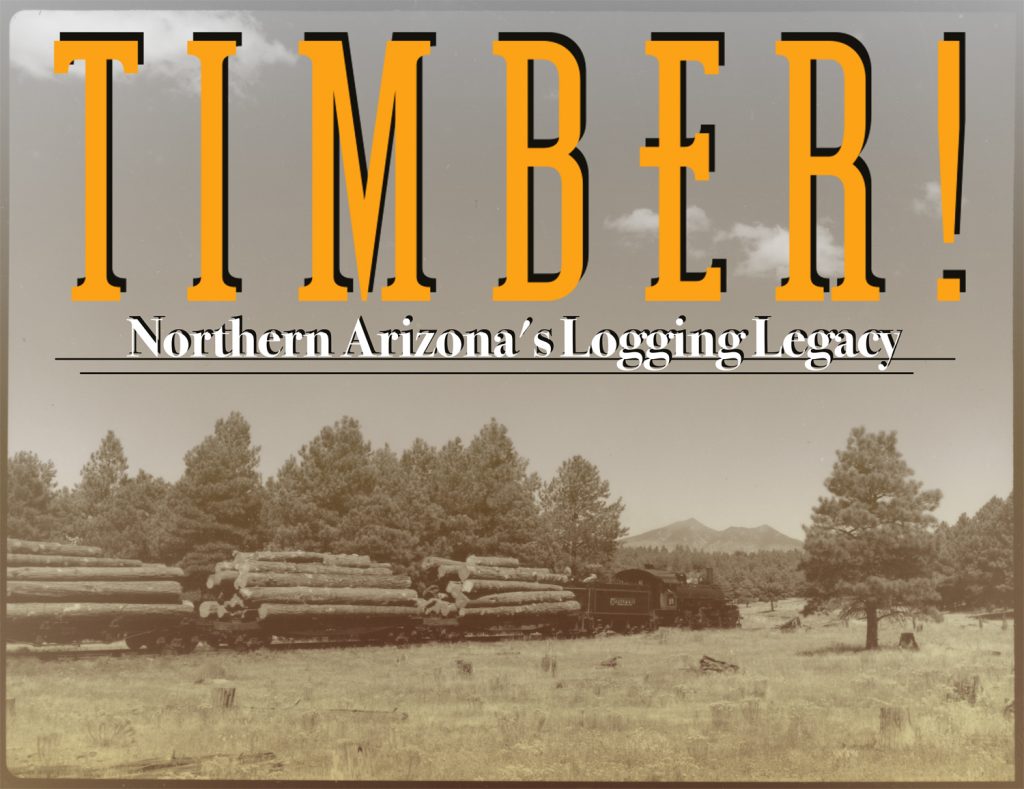

The Cline Library Special Collections and Archives (SCA) chose to encapsulate more than a century of this history in its exhibit “Timber! Northern Arizona’s Logging Legacy,” which uses authentic photographs, documents and diary entries from throughout the 19th and 20th centuries to outline northern Arizona’s evolving relationship with its forests. The exhibition will be on display in Cline Library’s SCA gallery until August 2025.

“The exhibit is a reflection on various approaches to living in a forested area from ancestral times to the present,” said Peter Runge, the head of SCA. “Our forests are confronting challenges from diseases and insects to a changing climate and human disturbance. While I’m not certain of the future of forestry, I imagine some answers will be found by looking into the past.”

Alexandra Williams, a senior studying history and comparative cultural studies, led the curation of the exhibit as the library’s 2024 Elizabeth and P. T. Reilly Intern. With a passion for environmental humanities and first-hand experience with the topic as captain of NAU’s logging sports team, she spent the last summer scouring the archive’s hundreds of collections and designing a compelling logging industry timeline with her mentors.

Williams also decided on the exhibit’s name, drawing on both the iconic shouts of historic lumberjacks and the identical battle cries of her logging team to connect the two generations of lumber lovers.

“The whole reason our brand is centered around the lumberjack is because of our logging legacy,” Williams said. “I hope that my exhibit brings the lesser-known history of Flagstaff to light, and I hope that NAU students will more proudly own their identities as NAU Lumberjacks.”

A history of trees and tracks

The roaring demand for local timber began in the mid-1800s when congressional plans for the transcontinental railroad included tracks cutting through northern New Mexico and Arizona.

Chicago businessman Edward Ayer saw the potential of the project and founded the Ayer Lumber Company in 1882, which became a primary supplier for railway ties using its Flagstaff sawmill. Five years later, the organization was sold to the Riordan brothers and promptly renamed The Arizona Lumber & Timber Company (AL&T). The business remained Flagstaff’s largest employer for roughly 50 years.

Before AL&T’s logging teams were felling as many ponderosa pines as possible for bridges, crates, structures and telegraph poles, at least 13 federally recognized tribes were living with and caring for northern Arizona’s landscapes as environmental stewards.

Because a lot of what modern ecologists know today about proper forest management and environmental reciprocity comes from Indigenous traditions, Williams said it was important that the exhibit acknowledge the forestry practices of the tribes who have and always will call northern Arizona home.

“In general, northern Arizona’s Indigenous communities approach resource cultivation with care and reverence and treat their relationship with the environment as two-sided,” she said. “By contrast, 19th- and early 20th-century Euro-American settlers to this area viewed timber as a resource and a commodity which they had dominion over. These different perspectives directly affected the way these groups interacted with their environment and, by extension, affected its ecological patterns.”

Following concerns of resource scarcity and environmental damage, the U.S. Forest Service began investing in forestry-related scientific research in 1905, founding one of the nation’s first forest research stations in Fort Valley about 7 miles west of Flagstaff. The forestry handbooks that station director Gustaf Adolph Pearson developed while working at the Fort Valley Experimental Station would serve as the foundation of NAU’s first forestry program in 1958.

With an inaugural class of 50 students, NAU was the first university in the Arizona-New Mexico region to offer a four-year forestry degree. More than 60 years later, students in this same program are making breakthroughs in land and fire management, climate studies and prescribed burn operations.

As more students get to know the logging industry’s connections to Flagstaff and NAU through her exhibit, Williams said she hopes people can learn from historical overuse and exploitation to foster a sustainable future for forestry.

“Environmental history and human activity surrounding the environment are critical factors to consider when making environmental decisions,” Williams said. “After all, humans are a part of the larger whole of our ecosystem, not separate from it.”

To learn about the first woman to graduate from NAU’s School of Forestry, how World War II caused spikes in lumber demand, what Pearson named his mules and more about northern Arizona’s logging history, visit the “Timber! Northern Arizona’s Logging Legacy” exhibit in person or online at nau.edu/special-collections/exhibits/.