Bovine babesiosis, or cattle fever, was once one of the worst diseases afflicting the U.S. livestock industry. Although the tick-borne parasite Babesia bovis was largely eradicated in the mid-20th century through a systematic USDA program to eliminate the ticks, cattle fever remains endemic in Mexico, where more than 60 percent of beef calves have been exposed to Babesia parasites.

As ticks develop resistance to pesticides, however, and infected stray cattle move across the border, the disease is at risk of being reintroduced into cattle populations in southern Texas. There is no vaccine for cattle fever, which causes anemia, fever and death in 70 to 90 percent of adult cattle that were not exposed to the parasite as calves. Virtually all U.S. cattle are naïve to the parasite, which makes them highly susceptible.

Securing the sustainability and competitiveness of the U.S. cattle industry

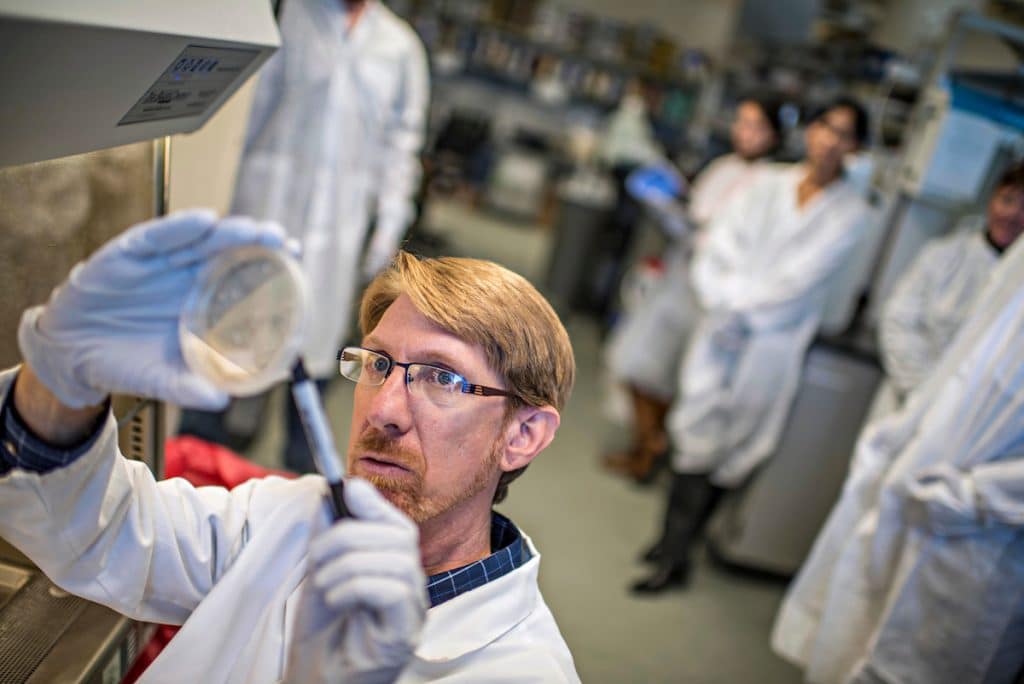

Joseph Busch, an associate director of Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute (PMI), is principal investigator of a new three-year study to develop genetic tools to prevent cattle fever from becoming re-established in the U.S. With more than 12 million head of cattle in Texas alone—and an estimated 94 million nationwide—the stakes are high.

“The goal of this project is to secure the sustainability and competitiveness of the U.S. cattle industry,” Busch said.

Funded with a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Busch and co-principal investigator David Wagner will collaborate with scientists of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) on the three-year project.

Acaricides—pesticides specifically formulated for ticks—remain the single most effective means of preventing cattle fever ticks from entering the United States. Also, anti-tick vaccines for cattle are used by some livestock producers to kill ticks before they can transmit cattle fever. Busch and his team will characterize genetic mechanisms of resistance to acaricide chemicals and identify genetic variation in tick genes that are high priority candidates for anti-tick vaccine targets. DNA fingerprinting techniques developed through years of research by Busch, Wagner and others in PMI will help provide data on the ticks, including whether the ticks sampled from Texas ranches are genetically related as well as their resistance to acaricides.

[block-quote align=”center”]The goal of this project is to secure the sustainability and competitiveness of the U.S. cattle industry.[/block-quote]

“Acaricides and anti-tick vaccines are the two primary management tools used to prevent cattle fever ticks and their diseases from entering the U.S.,” Busch said. “Our project will provide critically needed information to our APHIS collaborators who depend on these management tools.”

“Tick riders” round up stray cattle in the Texas quarantine zone

APHIS inspectors, called tick riders, ride horses along the Rio Grande on the U.S.-Mexico border looking for stray cattle that may carry the disease. They rope the cattle and direct them into a quarantine zone, where they sample the ticks and share them with researchers at USDA-ARS and NAU. The quarantine line has been breached repeatedly in recent years, and tick populations are moving northward, where they infest healthy cattle.

Busch, who has published more than 50 articles in scholarly journals, is one of the world’s leading experts on the genetic makeup of cattle fever ticks.

Kerry Bennett | Office of the Vice President for Research

(928) 523-5556 | kerry.bennett@nau.edu