A 1937 collection of poetry written by a group of sixth-grade Navajo children is one of the earliest records of Diné writing. The children were from Tohatchi boarding school in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the collection started a legacy of Diné writing that has continued to the present day with the release of the new anthology, “The Diné Reader: An Anthology of Navajo Literature.”

The anthology, published by The University of Arizona Press and co-edited by NAU English professor Jeff Berglund, demonstrates the power of Diné literary artistry, the persistence of the Navajo people and the perseverance against erasure. It combines Diné literature alongside interviews, biographies and photographs that feature each contributing author. Supplementing their stories is a chronology of important dates in Diné history and resources for teachers, students and general readers that further education about Diné writing.

“This work centers Native writers and specifically the voices of writers from one tribal nation,” Berglund said. “This work honors the historical developments and the emerging tradition of writing by Navajo writers, all while recognizing that there are many unknown writers who contributed in ways that may still be undocumented.”

Berglund has been a professor at NAU since 1999. In addition to being a professor, he serves as the director of the Liberal Studies program. He is a president’s distinguished teaching fellow and his research and teaching focuses on Native American literature, comparative Indigenous film and U.S. multi-ethnic literature.

Alongside Berglund were three other co-editors:

- Esther Belin, whose art and writing is widely published and focuses on historical trauma and the philosophy of Saah Naagháí Bik’eh Hózho, the worldview of the Navajo people. She serves as a faculty mentor in the Low Rez MFA program at the Institute for American Indian Arts (IAIA).

- Connie Jacobs, emerita professor of San Juan College who taught from 1993 to 2008. She often taught Diné writers such as Luci Tapahonso’s and Belin’s poetry to her students.

- Anthony Webster, a linguistic anthropologist whose research has focused on Diné poetics since 2000.

The book was a collaborative project that brought more than 30 Diné writers and artists together from the IAIA, Diné College, Navajo Technical University and several universities in the Southwest, including Northern Arizona University. The following contributors have ties to NAU:

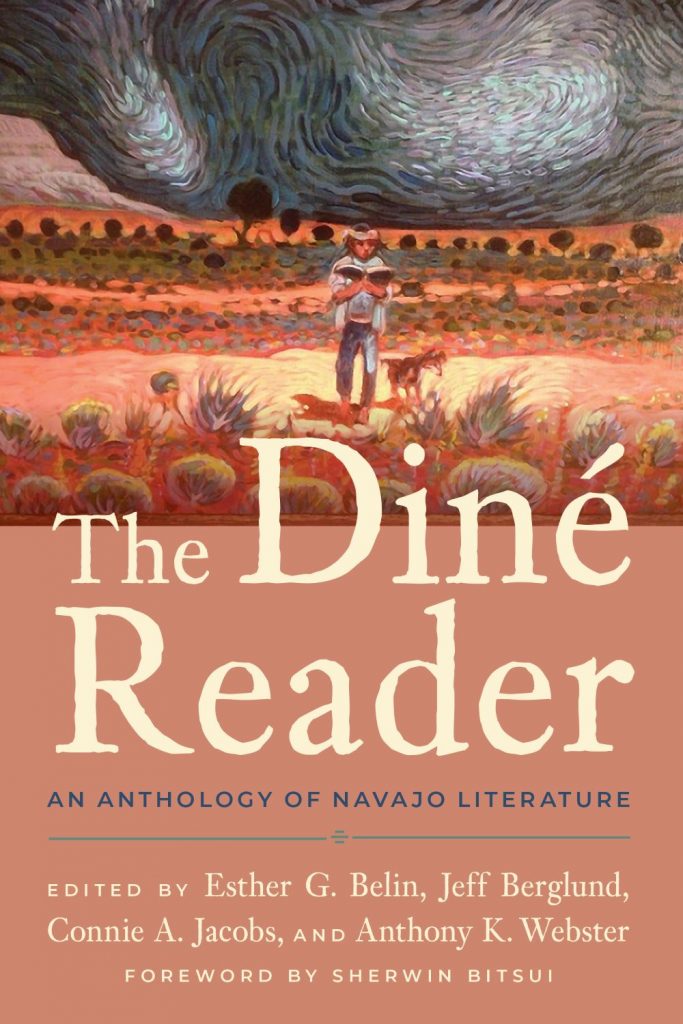

- Artist Shonto Begay contributed the cover design of the book. His artistic subject matter varies from daily Navajo life, desert and natural landscapes shifting to urban settings, road trips and ceremonial or social gatherings. He is a Flagstaff resident who served as an Artist in Residence for the NAU Honors College.

- Alumna Tatum Begay, who earned her bachelor’s and master’s from NAU, is a program adviser for Phoenix College and uses her free time to draw comics. In 2014, she started her webcomic series called The Pretty Okay Adventures of Tatum.

- Alumnus Erik Bitsui earned his bachelor’s from NAU. He DJs the Metal Meltdown on Flagstaff’s KSZN 101.5 FM radio. The subject matter of his writing varies and four of his pieces were published in the Waxwing Literary Journal in February 2019.

- Assistant professor of English Sherwin Bitsui wrote the foreword for the book along with several contributions in later pages. His work, inspired from Dinétah, has won numerous prestigious awards and grants.

- Alumna Norla Chee, who earned her bachelor’s and master’s from NAU, has published several pieces of poetry and short fiction and contributed poems from her book, “Cedar Smoke on Abalone Mountain,” published in 2001.

- Two-time alumna Jennifer Nez Denetdale was the first Diné to earn a doctorate in history at NAU. She is a professor of American studies at the University of New Mexico and contributed the Diné historical timeline for the book.

- Alumnus Bojan Louis is the author of the nonfiction chapbook “Troubleshooting Silence in Arizona “and the poetry collection “Currents.”

- Alumna Venaya Jay Yazzie is an artist, poet and photographer who contributed poetry to the anthology. She is a member of the Northwest New Mexico Arts Council and serves on the Navajo Heritage Cultural Center Board. In 2014, she was awarded the Mesa Verde Artist-In-Residence at Mesa Verde National Park and spent time on the Bisti Writing Project.

With so many different voices, the anthology offers stories that span several generations and gives perspectives on ideas about home, history and historical trauma, identity, language loss and the economic and environmental inequalities the Diné people have faced.

“We acknowledge the successful publishing careers of many of the contributors—and some that are on the ascent just now—so this book is not claiming that Diné writing is not known yet or that writers haven’t yet made their mark,” Berglund said. “Quite the opposite—this book offers readers the chance to see how influential and expansive Diné writing has been, where it originated, how it developed, how English and Diné bizaad have pushed against one another and how different literary forms have been shaped by Diné authors.”

The introduction to the anthology shares the story of the children from Tohatchi. There is no author credit given to each poem published in 1937; instead, they are credited as a group. The Tohatchi school was one of the first reservation boarding schools established in 1904. The Diné people were forced into these government-operated schools and “subjected to the imprisonment of language and thought.” The teachers used poetry and prose to teach the children English, but the Diné used it as an outlet to express what they were forced to repress.

Since then, Diné writing has had a tumultuous journey. Writers have expanded its reach, publishing many single-authored works, but the editors and contributors on this project found that both Diné and non-Diné students often still had little knowledge or exposure to Diné writing. Bitsui also notes in his foreword the misrepresentation he has seen given to the Diné people by detective mystery writer Tony Hillerman and how works such as Hillerman’s continue to cause a generalized misunderstanding about the Diné. This anthology was created to reverse that.

“We created this for Diné students—at the junior high, high school, college and graduate levels—and their teachers,” Berglund said. “Sherwin’s foreword mentions how frequently he met Diné students and readers who knew little about Diné writers. Connie Jacobs and I had similar experiences teaching at San Juan College and NAU.”

The editors saw this as an opportunity to create a multi-authored anthology that would allow readers exposure to many authors in one place—a starting point to find more.

Berglund said the detailed biographies and interviews of all living contributors is a service to the reader. The editors made a decision to foreground authors’ clans in Diné bizaad, the Diné language, as a signal to the value and meaning of those relationships.

Using Diné bizaad was an important part of the project, as forcing the English language on children in boarding schools was a form of cultural erasure. This anthology reflects all of this, showing the language transitions between English and Diné bizaad. Authors show mastery in both languages while showcasing the art of code-switching.

In the introduction, Belin and co-editors write that the collection “involved nitsáhákees (thinking), nahat’á (planning), iiná (living), siihasin (reflecting)” and acknowledge that much of Diné written work from the past is unknown—lost to diaries or kept private—but known or not, those works have contributed to this anthology.

Berglund said editors worked with family and estates to include work from two authors who have died but remain important to the Diné legacy.

“Persistence, asking different writers and different scholars led us to connect with everyone included.”

Editors want the anthology to help discover other lost works, continue the expansion of Diné writing and serve as an example of art that represents the Diné culture accurately.

In his foreword, Bitsui writes, “These stories restore memory and reconnect people, some of whom have moved beyond the sacred mountains to work and live in distant cities. These stories are doorways opening inward, back into the world that is always home.”

“We hope that readers and scholars locate other unknown and perhaps yet unpublished historical work by Navajo writers,” Berglund said. “We hope readers from current and future generations imagine themselves into this tradition. The last entry by Tatum Begay, ‘Stories of a Healing Way,’ meditates as to how her own writing will join her idols on her own bookshelf.”

The anthology has already received several positive reviews including praise from the U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. To expand the reach of the anthology further, The University of Arizona Press and Birch Bark Books in Minneapolis is hosting a free online book launch event at 6:30 p.m. on April 21. Eleven of the authors, the team of editors and special guests Jonathan Nez, Navajo Nation President, and Phefelia Nez, Navajo Nation First Lady, will be featured.

“We are excited about the reception of the work and for more and more readers here in the Southwest, in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, on the Navajo Nation and in nearby border towns, to learn more about this important literary tradition.”

Moving forward, interviews and podcasts are being set up with writers so teachers and readers have additional resources. #NativeReads, The Red Nation and Oak Lake Writers Society are contributing to these resources. All royalties from this project will support Diné writers and the development of future Diné writers, specifically through the Emerging Diné Writers’ Institute and other initiatives.

A previous discussion about the anthology can be viewed on the Northern Arizona Book Festival Facebook page. Forward Reviews has published a review and forthcoming podcasts will be available on The Red Nation Podcast.

Jacklyn Walling | NAU Communications