Oct. 2, 2018

As utility customers go, Northern Arizona University is complicated.

The dozens of buildings serve thousands of students, faculty and staff in a variety of ways—there are places to work, study, live, do experiments, play, eat and more. The campus is filled with people from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., but activity doesn’t end with a traditional workday. Even the work done on campus varies among buildings—some house office workers on computers, others have artists with kilns or engineers building machines, still others have dozens of freezers and heaters to properly store, test and destroy materials used for scientific research.

Knowing this, you might think a leaky air conditioner or less efficient lightbulbs would go unnoticed in the electric bill. But they don’t, thanks to a multi-faceted research consortium that provides hands-on analytical experience to engineering, sustainability and informatics students and workable, money-saving solutions to the Office of Sustainability and Facility Services.

“We’re trying to look at energy data in order to identify problems in the system, such as being able to tell that your heating and cooling controls aren’t working right or your refrigeration system is not working as efficiently as it used to, and why that is,” mechanical engineering professor Brent Nelson said. “Lots of times with these faults we’re just throwing energy away—wasting it because something’s not working right, a heating valve is stuck open, or something.”

“That helps NAU, because if they can know where those faults are they can fix them, and we can reduce our energy consumption.”

The project started with Ben Ruddell, an associate professor in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Security, and Karin Wadsack, a project director in the School of Earth and Sustainability. Wadsack was co-chair of the campus’s energy action team for the environmental caucus with Jon Heitzinger, associate director of utility services, and they, along with then-sustainability manager Ellen Vaughan, discussed the sheer amount of data NAU collected on electricity, natural gas and water usage.

From there, a marriage of convenience materialized. The university has all of this data, but no one has time to analyze it. Professors had students who needed research and analysis experience who wanted to take on problems similar to what they’ll experience in their careers later. SES professor Erik Nielsen, who along with Wadsack teaches in the Climate Science & Solutions master’s program, mechanical engineering lecturer Jennifer Wade and Nelson joined Ruddell and Wadsack on the academic side, recruiting graduate and undergraduate students to analyze data, write reports and reach conclusions that in some cases could be put to use.

“We figured out a way to bring together our student projects, including both research projects and student coursework, with what campus facilities is doing on energy systems,” Ruddell said. “The goal there is to give students real-world experience and also to provide applied value to campus.”

Living laboratories

We all know colleges and universities have labs and do research. In a living laboratory, the entire campus and community is an innovative, user-driven laboratory. NAU is building on this concept with its diverse array of student research projects focused on energy efficiency.

Student power is one of the major natural resources of the university, one Nelson was quick to employ. He contacted undergraduate students who were eager to get research experience before applying to graduate school or looking for work. The skills required for this type of work, including data collection and analysis, creating and troubleshooting potential solutions and communication, all are skills engineers need in any type of work they’ll go into.

It’s not just engineers, either. The same is true in most fields where working with data is part of the job description, Wadsack said.

“It’s really important, if the students are going to be data scientists in the real world, whether in informatics, engineering or environmental sciences, that they actually get practice in learning how to deal with those situations,” she said.

Climate science and solutions master’s student Kyle England said this project provided experience using Excel to collect and analyze data, professional writing and presentations, and this project is on his resume. And that’s not all.

“It is important to the overall goal of sustainability at NAU, as the results from these projects can help inform decisions made to improve the university,” he said. “These projects are time-consuming, and those in charge of higher level sustainability and energy decisions simply don’t have enough time to get to every little project.”

Projects became internships, capstone courses and graduate-level research, with students looking at campuswide energy use, potential improvements to campus buildings as well as water use and solar panel use throughout the city of Flagstaff. For Taylor Asher, also a grad student in Wadsack’s class, knowing this was real work that could be used to benefit the university made it that much more important.

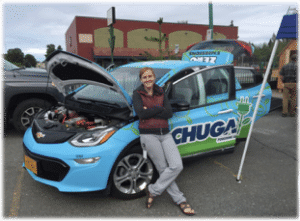

“Doing the energy analysis was probably the reason that I got my summer internship with Chugach Electric Association, the largest electric provider in Anchorage,” she said. “I see a huge opportunity for many more similar projects. It would even be worth employing students to work on similar projects of the university. It’s a win-win.”

Data-led solutions

Ruddell created a nationwide program that tracks communities’ supply chains using millions of data points. Without information, he says, people cannot make informed decisions. Knowledge in this case literally is power.

“We need data to do this,” Ruddell said. “We can’t spot problems and inefficiencies in campus energy use or in sustainability unless we collect data. It’s extremely important that universities that care about sustainability invest in data collection and in tracking things like energy use. There’s nothing we can do unless someone’s collecting the raw numbers.”

While he’d like more and better data, the information that is available gives researchers insight into what is happening related to energy and water usage throughout campus. One project, which master’s student Amin Sepehri did for his informatics class with Ruddell, studied the HVAC system, finding the strategies in use to control HVAC systems weren’t running properly. He wrote a computer program that looked at operational data and identified some faults, which Facility Services employees then could fix. He also analyzed the feasibility of a new thermal energy storage system for the university.

“We know the need for a sustainable energy supply is becoming more important with declining fossil resources, environmental pollution and climate change,” he said. “As a conscientious engineer, I want to be a part of the solutions that can prevent environmental calamities.”

While he worked with Nelson on those projects, Nelson also oversaw undergrads Kylie Dykstra, Daisy Liguori and Blake Hallauer who looked at NAU’s energy consumption data to see where he could detect and diagnose faults—areas that use more energy than they should be because of an error. Sometimes, that is simple—a building shouldn’t be running the heater and the air conditioner at the same time. Other times, such as with buildings where a variety of different types of research are happening, it’s not that simple.

Again, they analyzed the data, looking for numbers that didn’t seem to fit and could indicate faults that cost the university money.

“My undergrad team found a few problems early on, and we let Jon know right away that these are things that are hemorrhaging energy,” Nelson said. “If you’re wasting energy, you’re wasting emissions too. He’s gotten them resolved quickly.”

Graduate students in another of Nelson’s classes looked at what caused the energy peaks. North and south campus are metered separately, and north campus has a single peak time, but south campus had two. With more residence halls on the south, student researchers determined the evening peak was caused by students getting home, and it was correlated with sunrise and sunset, meaning light was probably the biggest factor in that peak. An easy solution? Energy efficient light bulbs.

“That’s most of what you can do,” Nelson said. “If you look at energy demand profiles throughout different parts of the country throughout the year, you can see in terms of occupant behavior what’s causing them. This is when people are coming home from work or waking up and plugging in coffee pots. You can actually see those peaks in load profiles.”

Energy consulting

The Climate Science and Solutions class that Wadsack and Nielsen taught in the spring was divided into three groups, each tasked with analyzing a specific question the energy action team asked.

“They were supposed to really think about all aspects of the problem,” Wadsack said. “They’re not actually doing that improvement in a vacuum. You have to take other things into account. There are ways you can do infrastructure projects in a building where you work around some issues, but you can’t just pretend it’s not there.”

Kyle England was part of the first group, which asked about updated insulation in Gammage. A number of years ago, NAU installed a unique type of insulation in Blome, which changes from liquid to solid as it changes temperature, which helps to keep the ambient temperature in the building steady. This had been a problem in Blome, with employees complaining about being too cold in the winter and too hot in the summer, so they were uncomfortable in their offices. The new insulation fixed that problem. England and his partner used energy data and conducted interviews to determine if a similar intervention would help in Gammage. Short answer? Yes.

Long answer? Thanks to the new insulation, the university is saving money on heating and cooling Blome; the upfront expense would be quickly recouped. But the biggest benefits aren’t financial.

“More importantly, the people who work in the building are more comfortable,” Wadsack said. “If you have someone who goes to work and needs a space heater and a sweater to be warm, they may be less productive and don’t really think of their work environment as a friendly habitat. If we fix that, they can be more focused on whether they’re enjoying the job and doing it well.”

“The students that worked on Geology said in their paper, ‘We’ve been uncomfortable in Geology,’” Wadsack said. “If they think their recommendations could make a difference, could help future students and faculty be more productive, if they could use their data analysis to help someone on campus make decisions about the future of buildings, to them it’s really powerful.”

The third group had a different task: to predict energy usage of buildings. They analyzed all available utility data, including electricity, natural gas and water, to attempt to create a statistical regression model designed to predict what usage would look like in a new building. They couldn’t do it, Wadsack said—not because the data didn’t exist, but because there was simply too much of it and it wasn’t specific enough. For instance, the Babbitt Administrative Center was in the same classification as the Health and Learning Center—two buildings with very different purposes and setups. More time and more detailed data could potentially achieve this.

At the end of the spring semester, the groups presented their findings to the class and to Vaughan and Heitzinger, who then offered feedback. The groups incorporated that feedback into the final report and turned it into Nielsen and Wadsack to be graded and Vaughan and Heitzinger to be used in future planning projects.

Next steps

England, who studied Gammage’s insulation, isn’t done. This semester, he plans to study the data for the summer and fall (for his class project, he only had time to study winter) and use that information to offer a more complete picture of the potential savings of the new insulation.

“The ultimate goal is to get a Green Fund proposal going to have this phase change material installed in the Gammage Building,” he said. “What I am able to do with this project during the fall semester will depend a lot on data availability and how much extra time I have for a side project.”

Wadsack is hoping future students will be interested in a different kind of project. She’d like someone to take on management of the data—cleaning it up so students can analyze it, finding holes, putting it all into one easy-to-access place so future classes can look at this data plus all the projects and analysis classes are doing now. Without good data, good solutions are almost impossible.

“Is it useful? Is it measuring things correctly? There are certain meters that just roll over every now and then, so if you’re not paying attention, you can end up with screwy measurements or data, or you think you’re measuring something and it turns out you’re not,” Wadsack said. “Teaching students how to deal with messy data or incomplete data or data that needs different kinds of manipulations or transformations is actually something we already do here.”

She also is collaborating with the other educators whose students are working on these projects to create a repository for all of the data, analyses, presentations and reports that have been done. This way, future classes will know what has and hasn’t been done, what data are missing and what questions needed additional work than a semester-long project allowed, and they can build on the research instead of doing it over again.

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu