By Heidi Toth

NAU Communications

Through millennia, glaciers have crept over Norway, their destructive nature carving the country into a wild and beautiful landscape filled with craggy mountains, steep waterfalls and crystal-blue lakes that reflect the rocks and sky.

Scott Anderson stands at the edge of these lakes, so clear that the details of the mountainsides are evident in the water, surrounded by towering rocks with the beauty of glacial Scandinavia in front of him—and he thinks about the mud at the bottom of the lake.

Specifically, the professor of paleoecology at Northern Arizona University wonders what secrets of early humans the mud has kept for millennia and what he can learn about how the residents interacted with a landscape that is inviting to the eye while seeming hostile to farming or otherwise building communities.

Anderson is part of a project, led by William D’Andrea of Columbia University and Nicholas Balascio of the College of William & Mary, that is piecing together what life on the Lofoten Islands looked like 2,000 or more years ago, when the people who later became the seafaring Vikings lived there. Lofoten is just below the Arctic Circle; as the glaciers melted and the sea levels rose, the mountain range turned into a rocky archipelago full of glacial lakes and small amounts of farmable land.

He’s asked the same question—“How do people utilize their landscape in their everyday lives, as part of their economy?”—in Spain, Scotland, France and Mexico, as well as extensive work along the California coast, using sediments from lake beds to measure human activity and evolution in areas or times when written records weren’t kept. This question matters not only because it allows researchers to learn more about pre-modern societies but also because it puts today’s society in the context of all the peoples who have come before.

“I think we just learn how early societies developed and how they interacted with their landscape,” he said. “It’s important because we are all part of that now. What they did back then contributed to the way we interact with the landscape today, and we wouldn’t know that unless we looked at these former societies and their landscape interactions.”

But yes, that has necessitated a fair amount of time studying muck.

“Whenever I go someplace else and I see lakes, this is what I think about,” he said. “I think about the mud at the bottom of the lake.”

Secrets of the lake bottom

Secrets of the lake bottom

Although other parts of Europe, including southern Norway, had written records two or three millennia ago, northern Norway didn’t. Using lake sediment, environmental scientists, archaeologists and Anderson, a historical or paleoecologist whose work straddles science and history, are able to piece together the basics of how that society functioned by studying what those people left. To the naked eye, it wasn’t much.

However, look hard enough and the signs appear. The mud at the bottom of these Norwegian lakes tells a story, preserved by hundreds of thousands of gallons of icy water. The newest sediment touches the lake bottom, atop thousands of years of sediment that has run from fields into streams and into the lake before sinking to the bottom.

The farther down the researchers get into the mud, the further back in Norway’s history they go. They’re looking for evidence of human activity in those layers of mud and muck. That evidence is invisible without a microscope; there aren’t human or sheep bones, iron tools or wool clothing preserved through the centuries.

Rather, Anderson and his team are looking at proxies—microscopic biomarkers that indicate the presence or absence of humans or grazing animals like sheep or changes in the levels and types of pollen, which could indicate changes in plant activity like a forest being cleared for farming.

“If you wanted to study agriculture in the past, one way to do that is to look at the remains of the pollen from the plants,” Anderson said. “Plants aren’t there anymore, people aren’t there anymore, so pollen could be a proxy for agriculture.”

Methodology

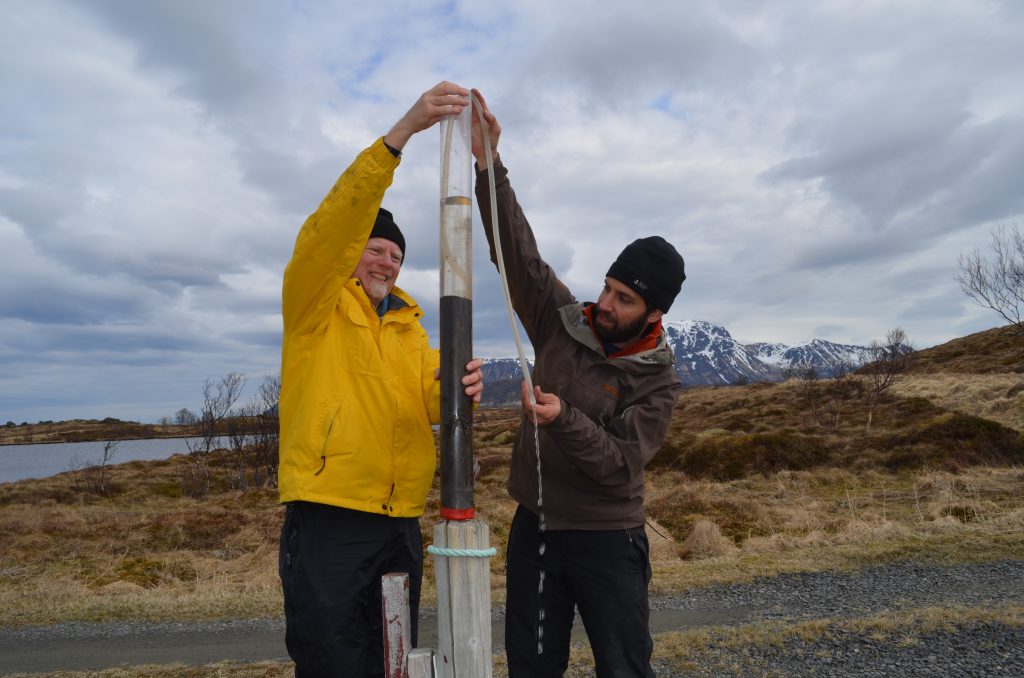

The team’s methods are straightforward. They go out on the lake in question and drop a float down to the bottom. Ideally, it slices right through the mud, going down until it fills up with mud, at which point they pull it back up. The sediment remains in its appropriate timeline.

At that point, all of the researchers take a sample of the mud, keeping the layers intact, and look for the proxy of their study. For one professor it’s a biomarker found in human feces. Another professor looks for a biomarker that comes from sheep. Still another looks for a biomarker released during burning, which could indicate humans built fires in the watershed. Anderson looks for the presence of pollen, what type of pollen it is and how the type and amount compare to the surrounding layers.

The changes in pollen presence will tell Anderson how the environment changed. For instance, at the lower levels he expects to find primarily tree pollen, which will indicate the land in the watershed is largely forested and thus likely uninhabited. As the sediment approaches the time when people inhabited the area, it’s likely tree pollen will be reduced because the forests are cleared and pollen from plants like wheat will increase because people are growing crops.

This all remains speculation; this particular project just started, Anderson said, and they are still in the mud-collecting process. But in other research he’s done in other lakes and research others have done on Lofoten lakes have seen similar activity.

This research allows the team to paint a more complete picture of what human activity looked like in this area. These early Norwegians are ancestors to the Vikings, who were seafarers and by about 800 A.D. became colonizers. Seafaring was already part of the culture; Anderson said fishing played a vital role in the Lofoten economy, and they traded dried codfish, their main export, throughout Europe and into Turkey and Russia. This eventually led to colonizing, although Anderson said researchers still can’t say what caused the change.

“We just know by looking at proxies what they did and the places they were living,” he said.

Learning from the mud

Although the people farmed what little land they could, the villagers around the lakes this team isn’t studying lived too high to farm, Anderson said. However, they likely raised sheep around these lakes and fished for cod, subsisting on what their landscape and hard work provided. They were living on the edge, Anderson said. If one variable changed, the Lofoten residents could have found themselves without enough food for a long and brutal winter.

This research also emphasizes the effects of a changing climate, both then and now. The climate allowed for agriculture and grazing to take place in some areas. In time periods when the sediment held less pollen, that could signify a reduction in the people’s ability to grow crops that could be caused by an unexpectedly early freeze, not enough rainfall or some other change that farmers of two millennia ago couldn’t regulate as farmers of today can.

“These societies didn’t have any ability to buffer climate change,” he said. “They lived and died on whether the growing season was long enough for them to complete their crop cycle.”

Although there are no written records from Norway from the time period Anderson and his team are examining, there are records from Europe they can use that may guide them in interpreting their data. He said they can compare when the Black Death hit Europe, wiping out a third of the population, to see if there’s a dip in human biomarkers that could indicate significant loss of life on the islands as well. Europe also experienced a major depression during the Middle Ages that could have meant fewer people and sheep living there.

“We can interpret the historical record in terms of these proxies, but it’s an interpretation. It’s not a correlation,” he said.

While this project can provide knowledge and context of a lost population and their relationship with the landscape, Anderson also has a personal motivation for his involvement. Here’s a hint: consider his last name. He is of Scandinavian descent.

That means what he learns about pre-modern Norwegian society tells him more about his ancestors. Such a personal quest is helpful in historical ecology, Anderson said. He encourages students to do genealogical work and know where they came from so they can do research in the context of their family’s history.

“We didn’t start with our grandparents,” he said. “There are thousands of generations before us that are part of our story, and by looking in the past, even the DNA past and environmental past, we get a much better sense of what it took to get us to where we are, what our ancestors might have had to go through to survive, to pass on their genes to the people that we are.

“And it’s a remarkable story. It’s not just a story of us here in Flagstaff. It’s a story of everybody in the world. We all have this remarkable story—a human story of individuals and societies and how we lived on a landscape for tens of thousands of years.”