By Karen Renner

Associate professor of English

Dr. Karen Renner studies American literature and popular culture; her research is focused on horror. She has written several books and articles examining the role of children in horror, masculinity in ghost-hunting, the influence of Edgar Allan Poe on serial killer narratives and why people are so excited for the apocalypse.

According to the National Retail Federation, this year “consumer spending on Halloween-related items is expected to reach an all-time high of $10.14 billion, up from $8.05 billion in 2020.” Most of that money will be spent on costumes, candy and decorations. But a hundred years ago, Halloween was associated with a very different tradition: finding true love.

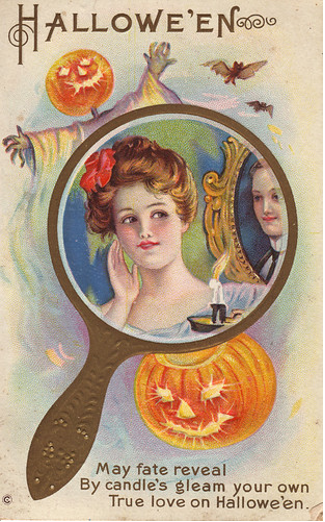

One of the most popular Halloween traditions at the turn of the 20th century involved a form of scrying referred to as catoptromancy, in which a woman would use a mirror to try to catch a glimpse of her future husband.

Postcards for the era frequently depict this practice:

Other versions of the practice were more dangerous in nature, asking women to look in a mirror lit by candlelight while walking down the stairs backwards.

The practice was clearly gendered in nature—women did the looking, men did the appearing. The presence of silhouetted witch figures in the background suggest that specifically feminine supernatural forces would aid women in their romantic endeavor.

Also central to the practice, though, was the use of candlelight. In fact, one postcard even includes a prayer to the “bright flame.”

Although the candle seems simply like an easy way to create an appropriately spooky atmosphere, it was likely also key to success of the experience.

The practice, you see, plays upon a strange perceptual quirk, what professor Giovanni Caputo has termed “strange-face illusion.” In an article published in Perception in 2010, Caputo described an experiment in which 50 individuals in their 20s were asked to stare into a mirror in a dimly lit room for 10 minutes and then record what they observed. Two-thirds of the participants reported seeing “huge deformations” of their own faces while almost half observed “fantastical and monstrous beings.” Other commonly reported faces witnessed were those of strangers, parents or animals.

In a subsequent experiment, Caputo discovered that the same illusions can be invoked when two people stare at each other for an extended amount of time. In fact, Caputo revealed that this version of the experiment resulted in a “higher number of different strange-faces.” One batch of people whom Caputo studied included several portrait artists who afterward attempted to draw what they had seen and the results are unsettling, to put it lightly.

So why is the strange-face-in-the-mirror illusion more likely today to yield images of monsters rather than mates, as it did a century ago? It’s likely due to our cultural associations with mirrors, which have increasingly become a staple of horror films in the past 30 years or so. Although this year’s remake of Candyman, originally released in 1992, is perhaps the most famous example, other lesser-known horror films such as The Mirror Witch (2020), Behind You (2020), Look Away (2018) and Oculus (2013) also play upon these fears. And it’s likely that our expectations about what we’ll see in the mirror when we stare into it shapes what we’ll actually observe.

Keep that in mind if you decide to go looking for love in the mirror this Halloween.