Henry Petterson remembers the shame he once felt about his Romani heritage.

While visiting family in small-town Montana, Petterson watched his white grandparents cover their couches with plastic, worried his mother’s dark skin would stain the fabric. He saw the way they kept his mother out of the kitchen, fearful she’d steal the silverware.

According to people like Petterson’s grandparents, the Romani—a nomadic people who originally came from northwestern India 1,000 years ago and who have since spread across Europe and the United States—were not to be trusted. Hundreds of years of rumor alleged the Romani, then called “gypsies,” were child snatchers and pickpockets.

“A lot of people might think this kind of discrimination against the Roma ended a long time ago,” Petterson said. “But for my mom’s whole life, and for a lot of my life, there was still a negative perception of ‘gypsy’ people. The last anti-Roma law was still on the books in New Jersey in the 1980s.”

For generations, Petterson’s family—immigrants to the U.S. who originally came from Prague and Čáslav in modern-day Czechia—swept their Roma identities under the rug for fear of being targeted. That only made Petterson more curious about where his ancestors came from and what their lives looked like.

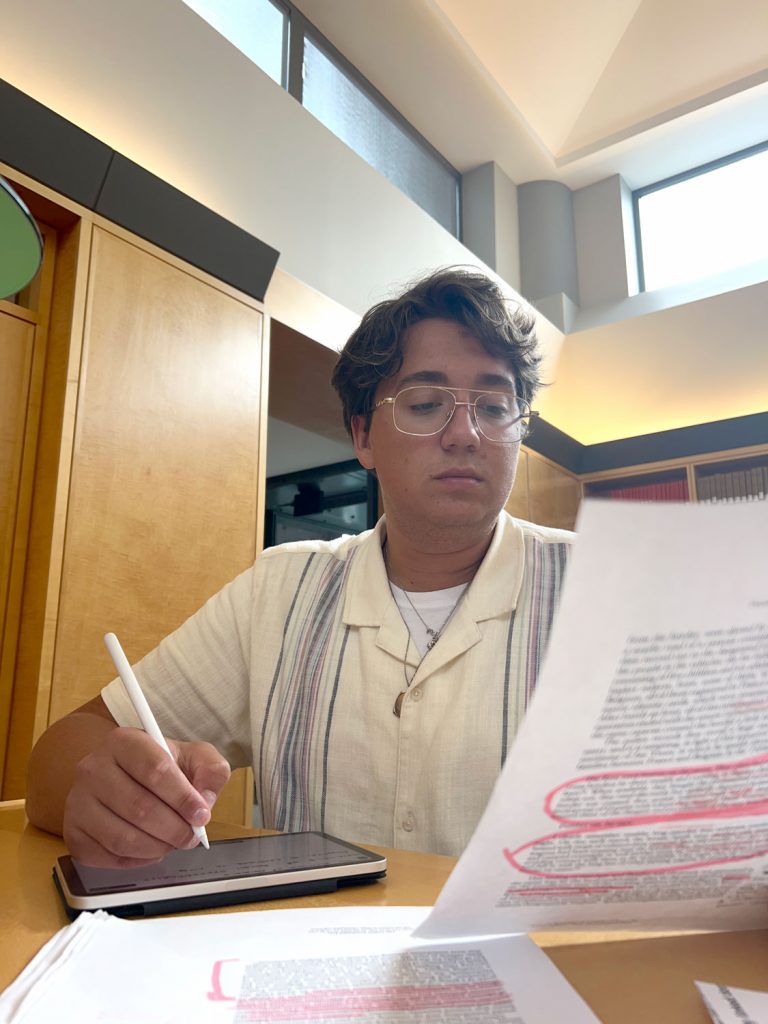

Now back in Flagstaff, the rising NAU sophomore and Honors College student spent part of his summer researching the history of anti-Roma sentiment at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., thanks to a scholarship from NAU’s Martin-Springer Institute. According to institute director Björn Krondorfer, Petterson’s well-stated passion for the subject landed him the award.

“We usually give this award to graduate students or upper-level undergraduates,” Krondorfer said. “But his project proposal and my conversations with him convinced us that, with his maturity and his ability to articulate his research interests convincingly, he was the right person for the award.”

Even though Petterson was driven to D.C. for personal reasons, his findings could have international implications: He was able to draw connections between the Nazi regime’s anti-Roma policies and similar discriminatory laws dating back to the 1870s, if not earlier.

“We tend to believe that all the anti-Roma policies that came out of the Weimar Republic came from Adolf Hitler because he was a harsh dictator and the mastermind behind the Third Reich,” Petterson said. “But you can see a lot of carryover from the second empire policies on Roma immigration and social treatment. For the Third Reich, it was like, ‘Of course we’re going to kill the gypsies. They’re criminals. They’re asocial. They have nothing to contribute to society.’”

Who are the Romani?

The Romani, also called the Roma, first migrated from India to the Balkans and modern-day Turkey around the 12th century. From there, they moved throughout Europe and across the Atlantic to North America. Traditionally, they lived a nomadic lifestyle, traveling from town to town and making money as merchants and artists.

Many leaders in Europe objected to the Romani presence in their communities, arguing that they took jobs away from local residents without paying taxes or contributing in other ways. While that might sound like a logical stance, Petterson said, the way European elites spoke about the Romani reveals that their criticism carried an undercurrent of racism.

“From 1750 onward, there was a strong push for the naturalization of citizens in their countries and this idea that there should be solid borders,” Petterson said. “People became patriotic, and these travelers were deemed inferior and uncivilized because they had not taken to this ‘settled’ life that everyone else had after the Industrial Revolution.”

That’s when anti-Roma sentiment intensified. In some places, it became codified into law. By World War II, it seemed inevitable that Romani people in Germany would end up in the same place as Jews: Nazi death camps. Though records are incomplete, historians estimate that between 200,000 and 500,000 Roma died in the camps.

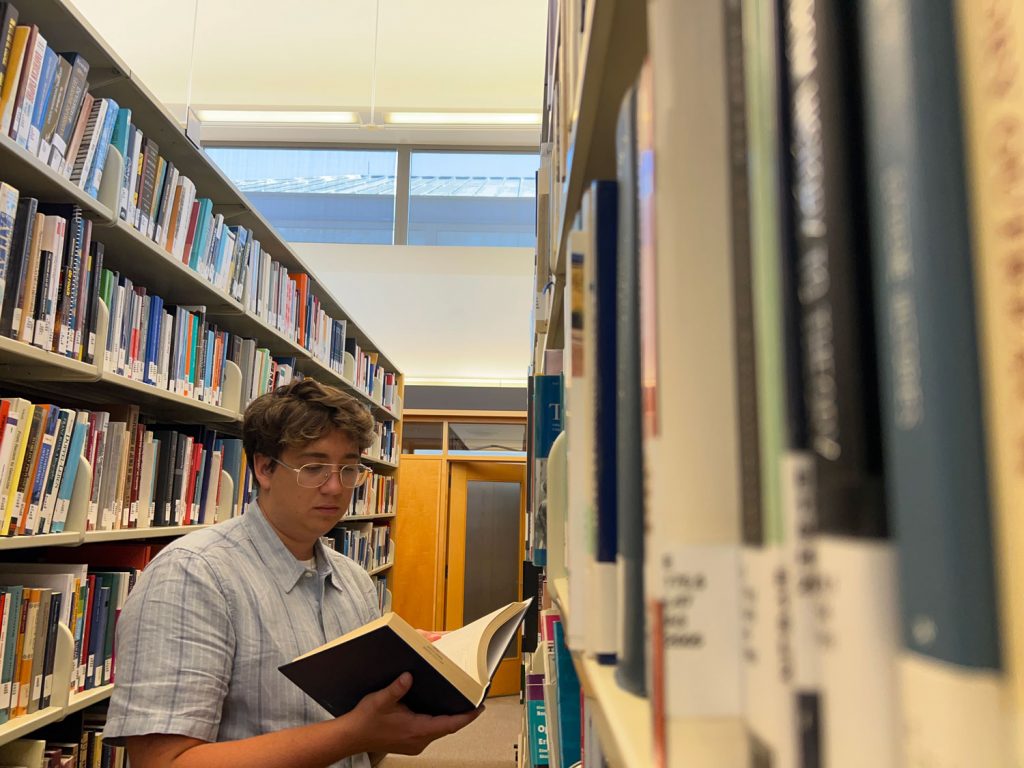

To trace this history of discrimination, Petterson logged countless hours in the Holocaust Memorial Museum’s library. He read historical documents, watched archival films and even consulted physical Roma artifacts, like their traveling equipment, musical instruments and suitcases confiscated at the camps.

Petterson hopes that someday, he can use his knowledge to educate people on the legal history of Roma discrimination by contributing to an exhibition or book. Until then, he’ll set his sights on a master’s degree in history and a career in teaching or in the nonprofit sector. Wherever he lands, he said, he’ll incorporate all that he has learned this summer, helping to advocate for the more than 10 million Roma living in Europe and the U.S. today.

“My No. 1 overall goal is to show people that just because I am Roma doesn’t mean I’m a thief,” he said. “I want to empower Roma people to be more proud of their heritage, and I want everyone to examine how their biases against the Roma create discrimination not just in laws but in society.”

Jill Kimball | NAU Communications

(928) 523-2282 | jill.kimball@nau.edu