Feb. 13, 2019

The story unfolds like an episode of a crime-solving procedural, with scientists in white lab coats laboring over hints left in the microscopic genome of a killer. Outside, a shaken nation waits. Law enforcement is at the ready. News anchors with serious voices share the latest. People stay at home and worry, admonishing their loved ones to be careful.

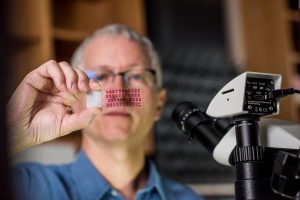

It’s a compelling drama, one microbiologist Paul Keim doesn’t need to see on TV. He actually lived it, cracking the code that determined where the bacteria that caused the fall 2001 anthrax attack originated and where it did not—Iraq—which put off the start of that war for a time and eventually led police to a likely suspect in the bioterrorism incident that killed five people.

Keim, a Regents professor of biology and director of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute at Northern Arizona University, shared his experience in forensics with fellow biology professor Frank von Hippel, an ecotoxicologist who hosts the monthly Science History Podcast. The conversation covered a range of such detective work that included a Japanese doomsday cult, the Soviet bioterrorism program and a rash of anthrax deaths among Scottish heroin addicts.

“Paul’s research history is so fascinating because he’s worked on all of these cases where forensic science is needed, using genomics to solve international problems in infectious diseases,” von Hippel said. “He’s done so many things in the last few decades—important political events and news events that had a significant scientific element to them. That’s what I wanted to tackle in this episode.”

Keim notes that “in a ‘live-fire’ situation, we were applying cutting-edge technology to a real-world problem and having to create new science to meet the challenge.”

During the 90-minute episode, Keim talks about his work with the FBI and the criminal justice system in the 1990s, which made him one of their first calls when anthrax showed up and federal investigators didn’t know the source. He recalls meeting the Gulfstream at the Flagstaff airport and taking the spores, which had been extracted from the first victim, back to his NAU lab. His team determined the spores came from a laboratory strain in the United States, not from an international enemy.

While that didn’t answer all the questions around the attack, which included anthrax spores being sent through the post office to news outlets and legislators, the discovery did drastically alter the conversation. Keim was a part of the global anthrax research community and was friends with the man eventually accused of perpetrating the attack—a chilling realization he recounts on the podcast.

“I’m pretty good at keeping secrets, but this was one secret I didn’t want to tell anybody,” he told von Hippel.

Keim and von Hippel discuss the laboratory-cultivated Ames strain of Bacillus anthracis, which is named for Ames, Iowa, but is not from Ames; how he developed a test that is able to identify that strain from any other strain in the world, even though the differences are miniscule; and where the “crime scene” was in the anthrax attacks, which allowed law enforcement to determine who were victims of bioterrorist attacks and who were affected by natural outbreaks of anthrax, which happen regularly in nature. (How anthrax spreads from dead animals to humans can be unpleasant.)

The podcast, which von Hippel started more than a year ago and now has listeners in more than 70 countries, is intended both to embrace his love of science history and to encourage science literacy among listeners.

“Science plays such a powerful role in shaping events of critical importance to national security and to our personal lives, so it’s great for people to have an understanding of what’s actually happening in the labs that leads to these outcomes,” he said. “I think for most people the science is a black box.”

The next episode, which will be released March 11, takes a look at game theory and cooperation and how international cooperation is rarely a zero-sum game

While some episodes are just about fun science topics, von Hippel’s primary goal is to equip listeners with the scientific understanding they need as they consider the difficult topics facing the world today.

“There are so many things going on, including all of these things for which people need to have a good understanding of science,” he said. “Hopefully, the podcast is a fun way for people to become better informed about science and understanding the history of discoveries.”

To listen to this and other episodes, including with Nobel Laureate Peter Agre, visit the Science History Podcast website or subscribe to the podcast on any podcasting app. Follow along on Twitter @sci_history. Follow Keim on Twitter @PaulKeim.