Ryan Chee is an elementary school principal and a sheep farmer. Every day, he gets up early to complete chores on his farm. Then he heads to his second job at Leupp Elementary, a rural school on the southwestern edge of the Navajo Nation.

After changing out of his farm clothes, Chee leads a daily meeting with all of Leupp’s students and teachers. Speaking both Navajo and English, he teaches them about hozhó, a Diné way of life that involves walking in two worlds. We all walk in two or more worlds, he explains—some of us are Diné and American; some of us are English speakers and Spanish speakers; some of us are sheep farmers and principals.

Before Chee came to Leupp, the school was in a precarious position by any measure. In 2021, Arizona’s school accountability system gave Leupp a D grade in student achievement, and 76% of kindergarteners were considered high risk for early literacy difficulties.

But three years later, under Chee, the school is excelling. Its state assessment has jumped two letter grades, and 75% of its kindergarteners are now considered low risk for early literacy difficulties.

What changed?

“What comes through to me is the importance he places on honoring the students’ languages, families and cultures,” said Rose Ylimaki, a professor of educational leadership at Northern Arizona University. “He’s putting that in dialogue with standard subjects like history, and it’s helping the students feel like they belong and like they’re a part of something larger. They’re more engaged. They want to learn.”

Ylimaki knows what makes a good school principal better than almost anyone. As co-leader of the International Successful School Principalship Project (ISSPP) at NAU, she oversees research that compares student achievement and school leadership at hundreds of schools in 27 countries to find out what some of the best principals in the world have in common.

After 20 years of research on schools and their leaders, Ylimaki and the ISSPP have found five core attributes that make a great principal—and, in turn, a great school:

- A drive to set clear directions and goals in collaboration with teachers, families and students;

- A positive, communicative relationship with students and their families;

- A democratic approach to administration, where teachers’ input on instructional styles is welcome and frequently solicited;

- A deep understanding of what’s going on in individual classrooms; and

- An explicit focus on equity.

“When you go to Leupp, you can see that Ryan Chee ticks all of those boxes,” Ylimaki said. “He’s helping students think for themselves. That’s important, because the future is an open question. Kids will need to solve problems we can’t begin to anticipate.”

Finding exceptional leaders

The ISSPP was founded in the early 2000s by Christopher Day, a leading education expert at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, in response to tectonic shifts in education across the globe.

In 2002, the United States established the No Child Left Behind Act, an education reform mandate that required schools to assess their students using standardized tests. At the same time, similar reform policies swept across the U.K., Brazil and Germany. In all of those countries, early assessment data showed that many students of color and students from low-income families were falling behind.

“Yet there were some schools—little pockets of them in each country—that were doing well for all students, regardless of background,” Ylimaki said. “We wondered what the leaders at those schools were doing differently. That was how the work started for us.”

DYK? Training good principals could be the key to solving Arizona’s teacher shortage. ISSPP research shows that principals are the primary reason teachers why teachers stay in, or leave, schools.

The researchers start by consulting student achievement data from states’ and countries’ education departments. Then, they compare those data with information about school principals and their tenure, keeping an eye out for schools whose numbers took a turn for the better after a leadership change.

Once they’ve identified those improving schools, the researchers contact stakeholders, including the district superintendent, members of school administrator associations, parents and teachers. Then they hold focus groups to find out how those stakeholders perceive the school and its leaders.

Once it’s clear to the researchers that they’ve found an exceptional leader like Chee, they visit the school, observe the principal at work and survey and interview members of the school community, including families, teachers and students themselves.

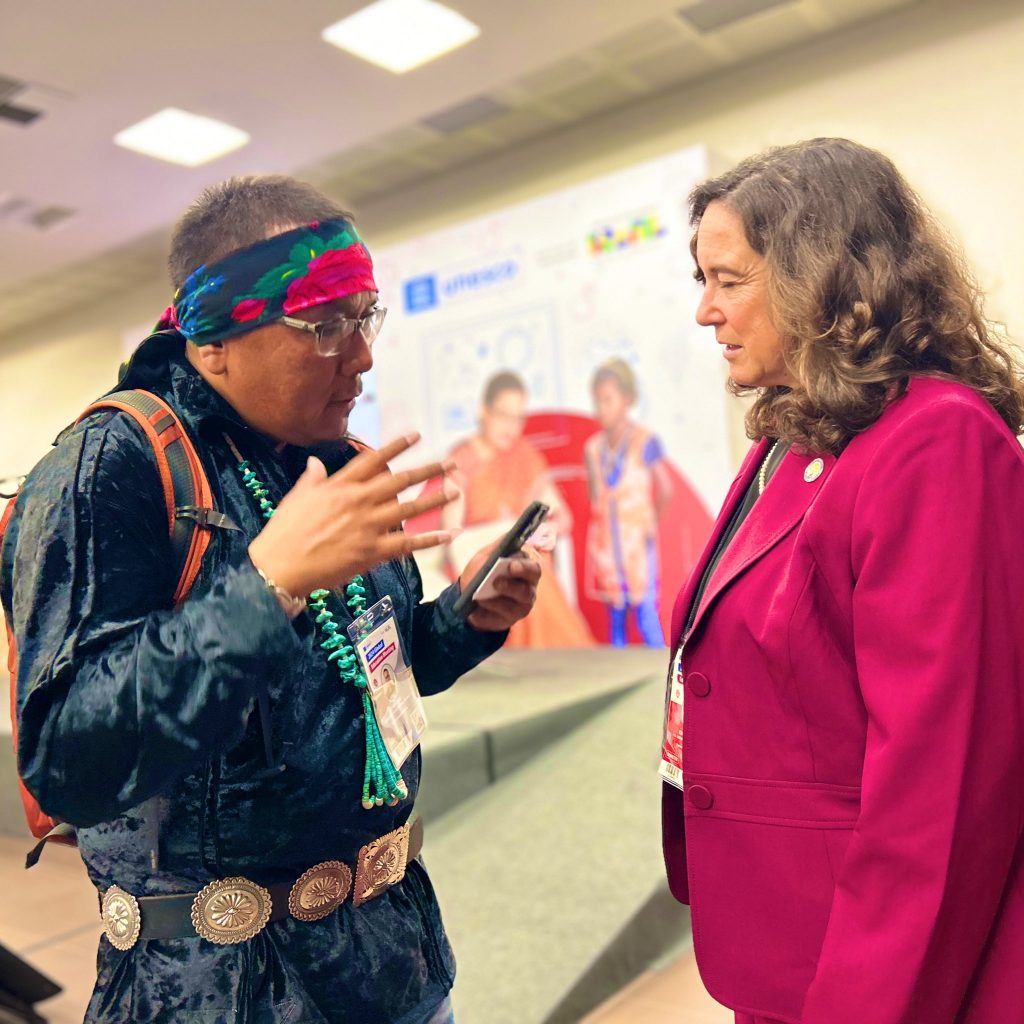

Ylimaki said the researchers frequently share their findings in peer-reviewed journals and international conferences for educators, including the European Conference of Educational Research and an ISSPP-organized research conference in London. And Chee is heading to Brazil this fall to present at the UNESCO Global Education Meeting.

“You take an Arizona principal to these conferences, and it helps them see that the challenges they face aren’t unique—they’re happening all over the world,” Ylimaki said. “Truly, all educators in this day and age are walking in at least two worlds, all the time.”

Leading in a changing landscape

Ylimaki said schools everywhere are changing rapidly due to factors like artificial intelligence, an increase in the number of international migrants and the recent COVID-19 pandemic. As schools change, principals need to change, too.

That’s why Ylimaki and her colleagues—including Joe Martin, Robyn Conrad-Hansen, Michael Schwanenberger, Donna Lewis, Mary Dereshiwsky and Lynnette Brunderman—use their rich research findings to teach the next generation of school leaders.

“We use these principals as case studies in my educational leadership classes to help students understand what makes someone effective and trusted,” Ylimaki said. “The hope is that our students will see how well these principals adapted their leadership style to fit the specific communities they serve, and they’ll remember that when they become principals someday.”

The researchers also harness their expertise in the Arizona Initiative for Leadership Development and Research, which helps improve student outcomes by supporting school leaders throughout the state. So far, the initiative has served leadership teams in more than 100 schools, often netting big improvements in student learning, schools’ assessment scores and community morale.

Ylimaki believes their work will only become more crucial as Arizona schools continue to change and diversify.

“Who could have predicted that the pandemic would change education the way it did?” Ylimaki said. “Who would have expected, 20 years ago, that we’d be such a global society now? I know I didn’t. We need principals, teachers and kids who are resilient in the face of change, because change will just keep coming.”

Jill Kimball | NAU Communications

(928) 523-2282 | jill.kimball@nau.edu