*Editor’s Note: The “Views from NAU” blog series highlights the thoughts of different people affiliated with NAU, including faculty members sharing opinions or research in their areas of expertise. The views expressed reflect the authors’ own personal perspectives.

By Michael Rulon

By Michael Rulon

Associate teaching professor, Department of Global Languages and Cultures

Michael Rulon holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. In addition to courses in French and Arabic language and cultures, Rulon also teaches courses in world cinema, including Global Horror, Global Queer Cinema and Revolution, Resistance, and Refusal.

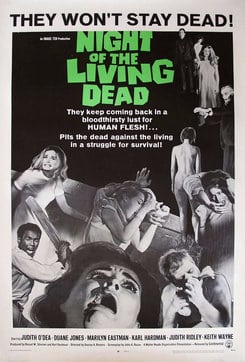

October is the time for horror films! Of course, if you’re anything like me, the rest of the year is also time for horror. I’ve been a fan of the genre for as long as I can remember; the first film I ever owned on VHS—at the age of seven or so—was George Romero’s classic zombie movie Night of the Living Dead. I quickly moved on to the slasher films of the ‘80s, the classic universal monster movies and some films that were more horrific than horrifying.

One of the most fascinating things about horror is the myriad ways in which it reflects societal values and collective fears. The evolution of the zombie subgenre is one of my favorite examples. In 1932, White Zombie, the first feature-length zombie film, dealt with anxieties about race, capitalism and colonialism. Thirty-four years later, Romero began his genre-defining series, beginning with Night of the Living Dead (1968), which addressed racial strife, the Vietnam War and nuclear warfare; Dawn of the Dead (1978) with its commentary on consumerism and individualism; and Day of the Dead (1985), which addresses thorny issues of bioethics. In subsequent decades, we see zombie films and series dealing with everything from biological warfare to climate change.

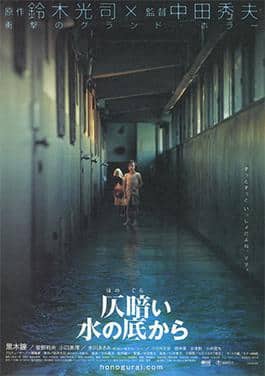

How does this play out in the rest of the world? Every country has its own culture and its own way of expressing its fears. If we look at the history of horror cinema across the world, we see an amazingly complex tapestry.

Let’s start with the oldest surviving feature-length horror film: The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, a masterpiece of German expressionism from 1920. This film gives us many of the horror tropes that we now take for granted: the distorted sets, the villain with exaggerated features and ominous shadows, among others. It would be a gross understatement to say that this film inspired Tim Burton’s style. But this is no mere mad scientist story. It’s a warning against authoritarian leadership, the very kind of leadership that led Germany into World War I just a few years prior. The funky style of the film isn’t a simple aesthetic choice; German expressionism began as a means of expressing inner conflict, but by the 1920s we begin to see filmmakers using it to express societal concerns about loss of control, violence and societal decay.

In 1959, French documentary filmmaker Georges Franju explores France’s collective guilt for its collaboration with the Nazi regime. Eyes Without a Face inspired the mask that Michael Myers wears in the Halloween franchise (as well as a song by Billy Idol), and it also caused audience members to faint in shock. Dario Argento’s 1978 film Suspiria examines neofascism via a twisted Disney-esque story of a coven of witches in a German ballet school. A list of Spanish horror films that comment on the legacy of Franco’s fascist dictatorship would take this article well beyond its word limit. The Spirit of the Beehive, Tesis and The Devil’s Backbone are just a few examples.

As you can probably tell, I could talk about this topic for weeks on end. In fact, I regularly do so—for 15 weeks, no less. If you’re the type of person who also enjoys exploring the complexities of horror cinema, you may consider signing up for LAN 350, section 1 in the spring semester. We can delve into the many layers of an Iranian-American feminist Western vampire film, an Oscar-winning Korean thriller about economic collapse and a First Nations zombie film about settler colonialism.

By Michael Rulon

By Michael Rulon