“Can you help me? I’m lost,” the homeless man said as he approached Cathy Small in the streets of downtown Flagstaff several years ago.

Most people would have brushed him off and continued on their way or immediately darted in the other direction. Luckily, Small wasn’t like most people. Without hesitation, she agreed.

As the two wandered around, looking for the HUD complex where a friend of his lived, they talked—about their days, about their lives and about the fact that Small happened to be writing a book about the trials and tribulations of the homeless population in Flagstaff.

What started as strangers walking with a purpose turned into acquaintances on a casual stroll.

“I feel so safe walking with you,” he said as they made their way through the streets of the Southside neighborhood.

Taken aback, Small evaluated the homeless man—20-something, large build, healthy and muscular.

“Why would you feel safe walking with me? I’m a 110-pound old woman!”

“Because I love to look at people’s gardens and admire houses, but if I do that when I’m alone, I worry people are going to call the police because they’re afraid of me.”

Not knowing what to say, she offered a smile, and the two continued on their walk, admiring gardens together.

It’s encounters like this that inspired Small, a professor emerita of anthropology at Northern Arizona University, to write the book, “The Man In The Dog Park,” published this month by Cornell University Press. Over the course of six years, she interviewed dozens of homeless people throughout Flagstaff to share their untold stories and shed light on the growing problems of homelessness in America.

“We all have the power to do something. And this book is my something,” she said.

The idea for the book grew out of a friendship with a homeless man she’d met at the Thorpe Bark Park where every morning, before work, Small would take her three dogs to run around and socialize. Oftentimes, she was the only person there, especially in the winter months when the sun had yet to rise. Then, one cold morning in November 2008, when Small arrived at the dog park, a sullen-looking man with an overgrown beard wearing a baseball cap and army jacket sat in the dark at a picnic table inside.

After much debate, Small hesitantly entered the fenced area, but made sure to stay near the entrance as a precaution.

The man didn’t acknowledge her coming or going, and the two kept to themselves.

Then, she saw him again the next day. And the next day. And the day after that.

After a few weeks of building up the courage, she sparked up a conversation and learned more about this mystery man in the dog park. His name was Ross Moore. He was homeless, living in the woods with his dog. He was a veteran, married once, and he was a convicted felon.

The more she learned, the more fascinated she became with his life.

Small started to look forward to her early-morning dog park visits, knowing she would see Moore and hear more of this story.

Over the next five years, Moore and Small developed a strong friendship.

If she was this captivated by his story, she was sure others would be too. And if this homeless man had such an interesting story, she was sure others did too.

So, she asked if he would be interested in writing a book together. After getting over the initial “you’re even crazier than me!” reaction, he agreed.

When the idea of a book came to fruition, Small reached out to Jason Kordosky, former student and NAU alumnus who did his master’s thesis on homeless day laborers, to see if he also was interested in collaborating. His research seemed relevant and his expertise was invaluable.

Using his knowledge as a starting point for her book, she took to the streets for real-life encounters.

“Ross introduced me to several of his homeless friends, and I began interviews there,” Small said. “Eventually, I just started approaching people through my own growing homeless network and invited them to participate.”

From 2013 to 2019, Small and Kordosky conducted a total of 75 interviews with 45 people in northern Arizona, ranging from panhandlers and day laborers to people who lived in their cars, on the streets or in storage units. Each had their own story and own struggles. Small realized that their homelessness was just about the only thing they had in common.

“I did a series of interviews with one man who was a panhandler. After the first couple, I realized that every time I would conduct an interview, it would take him away from panhandling. So, I tried to make up his lost income by buying lunch and offering what he would have collected from the hour we spoke. Other interviewees wanted bus passes, while some appreciated a restaurant voucher. A couple people just wanted a ride and others asked for $5 to order a warm meal at Burger King that allowed them to escape from the cold. No matter what I offered, they were always so grateful.”

Over the years, the interviewees made an impact on her. Not only did they help change her mind and opinion toward homelessness, but they opened her eyes to a world she realized she knew nothing about. She found herself running into the same people and feeling connected to them and their way of life.

“I hope after reading this book that people come away with less fear of and greater compassion for homeless people—I know I did. More often than not I realized homeless people don’t fit the mold society has created for them; drugs, alcohol or a mental illness were not singularly to blame for their circumstances. What I found to be true is that a lot of these people were in the situations they were because of a manifestation of growing wealth differences in the U.S. and a thin line between being poor and being homeless.”

Small also realized that, despite what people may think, it takes a lot of work and ingenuity to live without a home. You have to be organized, more thoughtful about from where your food will come, how you are going to shower, what your basic necessities are and will they fit in your backpack, she said.

“As Americans, distancing ourselves from the homeless obscures our understanding and limits our compassion contributing to their suffering. I am hoping that this book will bring to light issues like affordable housing, minimum wage increases, addiction treatment or prison-to-work programs that might help the homeless. I don’t expect everyone to be open to a homeless shelter opening up next to their home, but I do hope more people decide to look carefully at what they can do to help this population and initiatives that benefit them.”

Whether we’re lost, hanging out at a dog park or just wanting a warm meal, at the end of the day, Small thinks there isn’t much difference between them and us.

“Everyone should be able to admire gardens without fear.”

Small would like to remind readers that in light of COVID-19 and homeless peoples inability to shelter in place, donations to Flagstaff Shelter Services or United Way of Northern Arizona goes a long way in helping this population.

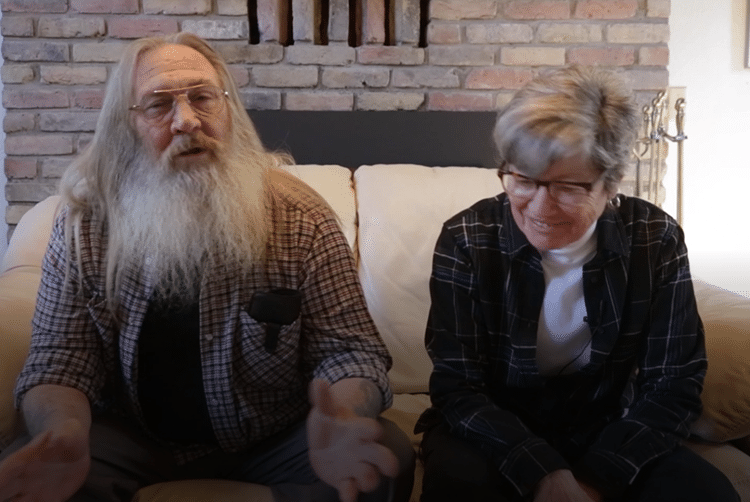

To preview the book, watch Small and Moore in an interview about Coming up Close to Homelessness: The Man in the Dog Park online, produced and edited by NAU communications major Blake Silkey.

(928) 523-5582 | carly.banks@nau.edu