Jersus Colmenares López was born in southwestern Venezuela near the Colombian border.

The child of a plumber and a vocational school teacher, his parents came from extreme poverty, but were determined to provide the best lives possible for their children. Colmenares López grew up without luxuries, but had a roof over his head and food in his belly—more than most of the children in his town could say. Most importantly, he was loved.

At a young age, Colmenares López was diagnosed with an immature, hyperactive brain, but his mother refused to allow this to define her son.

His parents sought help from the best doctors, traded work for medical help and also saved to pay for medical assistance that was beyond their means. None of the medical advancements at the time were helping, so his mother decided to act on her own. She stayed home to educate Colmenares López, paid tutors—a rare thing in rural 1980s Venezuela—read books and asked for advice from psychologists and other human mind experts.

Determined to prove his doctors wrong, Colmenares López’s parents enrolled him in art school and taught him how to play musical instruments, swim, cook and iron clothes at an early age.

[block-quote align=”center”]One memory I treasure is my mother’s scandalous request to a welder to make me a left-handed school chair, something that was culturally and superstitiously frowned upon by people back then—and something much harder for a child to take to. She made the school accept the chair in my third-grade classroom.[/block-quote]

They also enrolled him in an English-speaking school. Every day, his father would drive him and his siblings the hour-long commute to the school in another city to make sure they were getting the best education possible.

“My dad bartered with a bank owner who had grown up with him to get us a computer in exchange for building a massive water tank for her house,” Colmenares López said. “He got the computer for us to learn, something only the wealthy could afford. But my dad was convinced that we could do just as well as others with more possibilities.”

When it came time for college, thanks to the unwavering support and encouragement of his parents, Colmenares López decided to pursue a higher education. Though college in Venezuela was technically free, not all could afford the expenditures associated with earning a degree. With no money for textbooks, technology or other resources, Colmenares López had to work three jobs to be able to stay in school.

“My teachers gave me the opportunity to become a teacher’s assistant and also made me responsible for the language lab. When I finally received my first real paycheck, I paid for my dad’s car repair. Though it took the whole check, I never felt so rewarded in my life. For the first time, I was able to help my family, instead of the other way around.”

Colmenares López graduated with his bachelor’s degree. But he was just getting started.

“If my mom did it with the shoes, school dress and book that her neighbors donated so she finally could go to first grade at the age of 11, I have never had a real excuse not to try harder, move forward and succeed.”

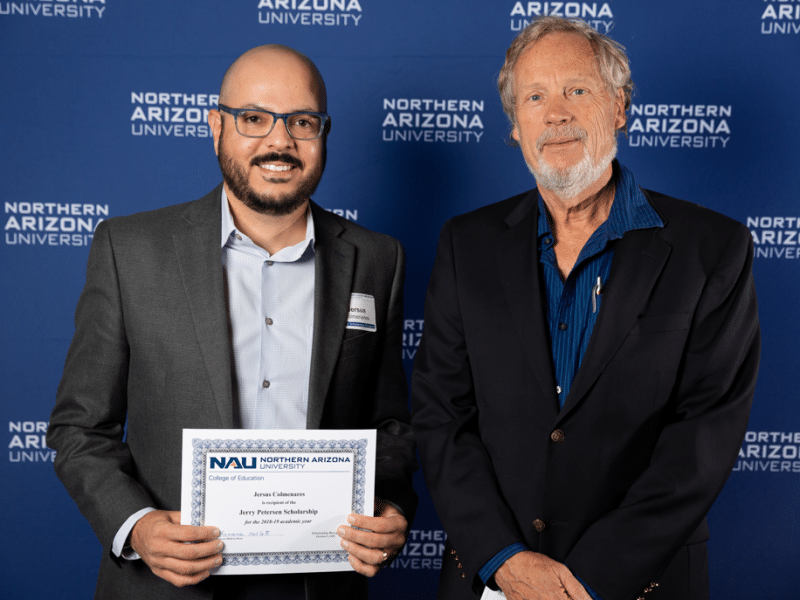

A Fulbright Program grant allowed Lopez the opportunity to pursue a master’s degree in the United States. Through the process of researching universities abroad, a Department of State official suggested he look into Northern Arizona University. After discovering the author of one of his favorite textbooks was based in Flagstaff, he was sold.

He enrolled at NAU in 2006.

After completing his master’s degree, he felt compelled to pursue a doctorate degree with the hopes of creating interfaces that would translate highly beneficial research findings about language into education solutions for students and teachers. But, tension between Venezuela and the U.S. sent him and his wife back to their home country.

Three years later, his former NAU professors encouraged Colmenares López to apply for admission to the curriculum and instruction doctoral program and fulfill his academic dream.

[block-quote align=”center”]I came back to Flagstaff to continue my doctoral studies with my wife, three children and $10. With almost no diplomatic or consular relationships between my country and the U.S., it simply was a miracle that we were given visas to come back to NAU.[/block-quote]

Over the course of the next couple of years, Colmenares López faced a number of challenges, particularly in terms of immigration, and most importantly in terms of keeping his family fed and sheltered.

After his country refused to give them new passports, problems with immigration documents, extensive visa requirements and what seemed to be endless obstacles, Lopez’s wife and children received a notice of deportation.

“It was sincerely really hard to process that after so many efforts to always do things right, we now were at risk, and without much hope,” he said. “However, we had help from friends and the NAU community that covered the costs of passport extensions.”

With his family safely in the U.S., the worst was behind them, or so they thought. López’s wife starting experiencing an array of health issues that required an important surgery. Raising three kids, with a sick wife, while working to provide for his family and complete his Ph.D. would have been debilitating if it weren’t for the assistance he received while at NAU.

“Louie’s Cupboard fed us when we didn’t have much to offer to our children, and the NAU LEADS Center provided wonderful opportunities for my children to live life in a joyful and meaningful way when we could not afford to take care of our family,” Colmenares López said. “It is not a secret that we, non-traditional students, face poverty throughout our studies, and our families with us. But fortunately, we didn’t go without. We were and are blessed with being under the loving care of NAU’s human hearts and generous hands.”

In the final year of his degree, Colmenares López worked as a professor in the Department of Global Languages and Cultures, developing his dissertation out of the perceived need to help his students learn Spanish in more meaningful and effective ways.

“As a foreign national who was received and nurtured by the NAU family, I feel my place is here,” he said. “Teaching at NAU is not just a job for me. It has meant and continues to represent one of the best opportunities I’ve ever had to be part of an inspiring and thriving community that collectively seeks the good of the other.”

Without the sacrifices of his family, Colmenares López would never have found his way to NAU—he credits them for his success. Under extremely difficult circumstances, they will be watching him walk across the graduation stage, more than 3,000 miles away.

“Honor a Jesús y Benilde Colmenares López, los mejores padres que pude tener. Con profundo amor, Jersus.“

Carly Banks | NAU Communications

(928) 523-5582 | carly.banks@nau.edu