Could the plants growing along roadsides and between buildings in Flagstaff help reveal where fossil fuel emissions are highest and lowest in the city? A team of NAU researchers thinks so. As part of a new $25M award from the U.S. Department of Energy to build a statewide Integrated Field Laboratory to study extreme heat, air pollution and their impact on people living in urban communities, the NAU team will work with researchers, community groups and plant enthusiasts across Arizona to test plants’ capabilities as hyperlocal sensors of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel use. The NAU team and its plant partners will not only help scientists track street-level emissions in Arizona’s cities and towns but could also forge a blueprint for building a reliable and high-resolution fossil fuel emissions tracking system across the United States.

The new center, dubbed the “Southwest Urban Corridor Integrated Field Laboratory” (SW-IFL) and led by principal investigator David Sailor of Arizona State University, is anchored at the state’s three universities and involves teams from Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York and industry partners. Using the sprawling urban regions of Arizona as a living laboratory, the team will engage communities reaching from the border with Mexico to the Navajo Nation and provide scientists and decision-makers with high-quality, relevant knowledge capable of guiding responses to the air quality, extreme heat and limited water problems that the state faces.

The project is a chance to create information about these challenges that leaders can act on, said NAU SW-IFL lead investigator Kevin Gurney. “In the past, we researchers haven’t always done a good job connecting the physical sciences with the socio-economic realities on the ground,” he said. By thinking about how policies and the built environment interact with physical processes like carbon emissions and heat, Gurney said, “we’re really trying to do it differently this time.”

Harnessing plants’ natural fossil fuel detection powers will require a combination of shoe leather, crowdsourcing, an NAU-based emissions model called Hestia and a sophisticated machine housed at NAU, the Mini-Carbon-Dating-System (MICADAS). Scientists can use this mass spectrometer to measure the carbon a plant has absorbed into its stem and leaves. Then they need to identify the portion of that carbon that came from burning fossil fuels, which are too old to carry radiocarbon, an isotope that occurs in the environment both naturally and from nuclear weapons testing. (Read this great explainer from KNAU about how the MICADAS machine works.)

“This project lets us ask questions about tracking fossil fuel emissions in a rigorous and community-based way,” said Ted Schuur, Regents’ Professor of biology in the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society at NAU and one of the leads at the Arizona Climate and Ecosystems (ACE) laboratory. “Can an annual plant in Flagstaff ‘see’ the fossil fuels in the atmosphere on the city block where it grew? How local is our airshed, and can the plants in our parks help us figure that out?”

Once the team learns how precisely common plants can sense their local atmospheric CO2, they will invite people and communities across Arizona to collect and send plants to be sampled at NAU.

Helen Rowe, an associate research professor in the School of Earth and Sustainability at NAU, will connect with community organizations across Arizona to recruit “community scientists” to help map these emissions from the ground. A community scientist could be anyone who wants to learn about plant sampling or is interested in tracking fossil fuel emissions in their community.

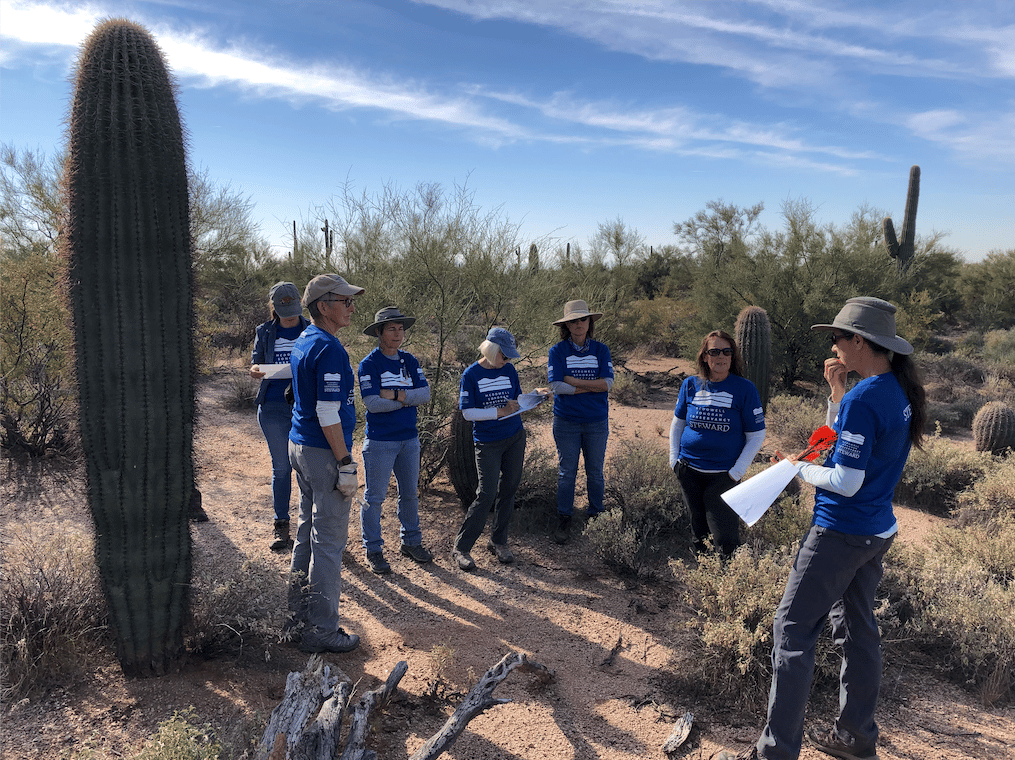

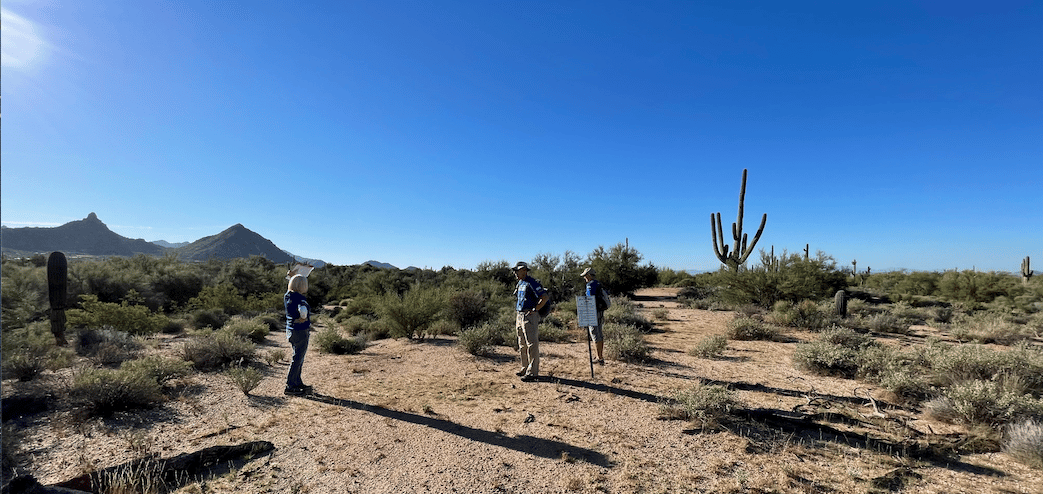

Rowe, who also works as an ecologist with the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy, said getting diverse communities involved across Arizona is an essential part of the SW-IFL project because volunteers bring important perspectives that are different from those that academic scientists bring. “Volunteers can bring in details from the ground,” said Rowe, who includes volunteers as co-authors in some of her research. “They bring wonderful insights that they have from being out there, collecting data.”

While collecting and sampling these plants in the ACE lab, the team will begin to draw an emissions map of Arizona’s urban areas. That’s where the Hestia Project comes in. Designed by Gurney, a professor in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems, Hestia is a high-resolution, living map of urban fossil fuel CO2 emissions based on what we know about the physics of emissions, atmospheric sampling and a whole lot of math.

The Hestia project has estimated emissions in the air around several major cities on a block-by-block scale and matched atmospheric samples closely—within three percent.

“Evaluation against the atmosphere is crucial,” Gurney said. He added that the unique approach of community-based plant sampling to evaluate his team’s model is more cost-effective and potentially more precise than other air sampling techniques currently used to verify atmospheric CO2 concentrations. “The great thing about plants is that they’re right down where the emissions are, doing their job, meaning they are natural integrators of the carbon signal,” he said. “This technique takes advantage of that.”

The new SW-IFL will leverage these estimates in other ways, too. Merging Hestia’s information with a building energy simulator at Oak Ridge National Laboratory will allow the team to project the heat burden in different parts of Arizona cities. Heat varies widely in urban centers and affects people inequitably; numerous studies have shown that people of color and lower-income communities in urban regions are most vulnerable to heat-related health issues.

“DOE has a long history of leading in climate science and climate modeling,” said Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, Director of the DOE Office of Science. “In addition, the Urban IFLs are an important element of the Office of Science’s commitment to the ’Justice40 Initiative,’ which prioritizes investment in diverse and minoritized communities affected by a changing climate.”

“I’m hoping this pilot project in Arizona is going to be a model for how to do this everywhere,” Gurney said. “If we can tackle a domain of that size, and show it works, we can really begin to look at supplying this data for the whole U.S.”

Gurney believes that it’s critical to help communities and regions better track their climate change mitigation efforts and to assess how they are meeting—or falling behind—their emissions reduction goals in a standardized, verifiable way.

“If you mitigate, it should show up in the atmosphere,” Gurney said. “That’s the only place where it matters.”

* Read more about the new SW-IFL at ASU and University of Arizona. Individuals or communities interested in helping collect plant samples may contact Helen Rowe or Ted Schuur.

Kate Petersen | Center for Ecosystem Science and Society