Since the diversion dam was removed from Fossil Creek in 2005, the 17-mile river that travels the border of the Coconino and Tonto national forests has become an idyll for indigenous wildlife species and visitors who swim, hike and fish. Its travertine pools and waterfalls frequently grace calendars and the pages of Arizona Highways. The river has also become a laboratory for researchers like the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society’s Jane Marks, who uses Fossil Creek to study how carbon enters freshwater food webs and what that means for these ecosystems and the global carbon cycle.

The starting place for Marks’ investigations is the seemingly ordinary act of a leaf falling in a stream. In a recent paper published in Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, she traced the pathways that elements in leaves, such as carbon and nitrogen, take when they drop from trees into a river and how those pathways help determine the health of the river ecosystem. Much work on the decomposition of dead leaves focuses on the rate of decay: how fast do nutrients go away? But Marks is curious about where elements go after they’ve left the decomposing leaf.

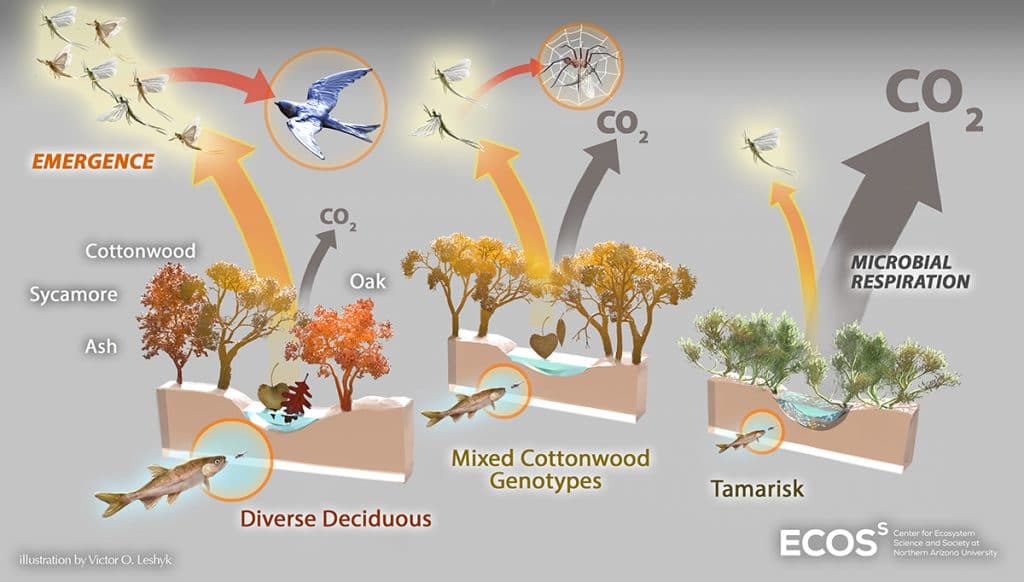

To answer this question, Marks and her lab conducted leaf litter experiments and stream monitoring at Fossil Creek and other nearby streams to better understand how nutrients travel from decomposing leaves to microbes and macroinvertebrates like caddisflies, mayflies and midges. Just as it’s important to figure out the fate of our own trash after we throw it away, so too is learning what factors determine where elements go next in the aquatic food web—and how warming and biodiversity influence these fates. The information Marks’ team is gathering can inform carbon cycle models and decisions about river restoration and management.

Now Fossil Creek is about to enter a new phase. Designated a Wild and Scenic River by Congress in 2009, the river is now managed and protected by the U.S. Forest Service, which has worked with conversation groups, managers, citizens and researchers like Marks to develop a Comprehensive River Management Plan. This plan will guide management decisions to protect and enhance the river’s biological, geological, cultural and recreational values. And because of its importance to the Western Apache and Yavapai people, the river also is in the process of being nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a Traditional Cultural Property (TCP).

The Forest Service is working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to draft the environmental impact statement for the plan, said Marcos Roybal, Fossil Creek project coordinator. The Forest Service plans to release a draft in June and then meet with stakeholders who weighed in on the plan’s development. Roybal said his team hopes to release a final management plan by the end of 2020.

Marks said the process has been an important one with which to be involved.

Kate Petersen | Center for Ecosystem Science and Society