On Oct. 16, NASA launched the Lucy probe, starting its 12-year journey to the Trojan asteroids near the planet Jupiter in the outer solar system.

Expected to begin reaching its targets in 2027, the probe will fly by more asteroids than any other spacecraft in history, including one in the “main belt” between Mars and Jupiter and eight Trojan asteroids—Donaldjohanson, Eurybates, Queta, Polymele, Leucus, Orus, Patroclus and Menoetius.

“The Trojan asteroids are leftovers from the early days of our solar system, effectively the fossils of planet formation,” said Hal Levison, principal investigator on the Lucy mission.

Because the asteroids are fossil-like remnants of our solar system’s origins—having changed very little in the 4.6 billion years since they were formed—they are ideal for studying conditions in the early solar system. Scientists have designed Lucy to fly by and carry out remote sensing activities to achieve mission objectives by mapping surface geology, surface color and composition; study the asteroids’ masses, densities and sub-surface composition; and look for rings and satellites of the Trojans.

Lucy will travel four billion miles in all, reaching speeds of up to 92,000 mph (150,000 kph), which means every step of the mission must be executed flawlessly.

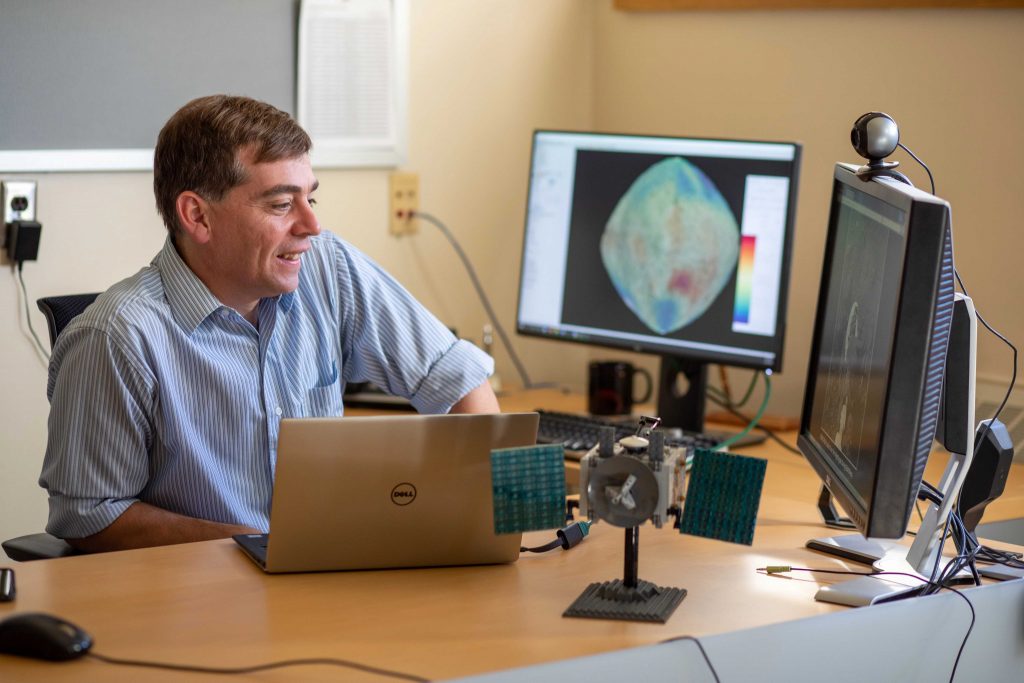

Planetary astronomer Josh Emery, professor in Northern Arizona University’s Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science, leads the Surface Composition Working Group (SCWG) for the mission. It’s his job to help plan the observations of the targets that are required to answer the open science questions about Trojan asteroids. The group will determine what materials the asteroids are made of as they search for ice, complex organic molecules and rocky material that will indicate where in the solar system the Trojan asteroids formed.

“The launch of Lucy was truly fantastic,” Emery said. “I have been studying the Trojan asteroids for my whole scientific career, since the 1990s, and I cannot wait to see these bodies close up.”

NAU Ph.D. student Audrey Martin also is heavily involved on the Lucy team. She has been studying data of Trojan asteroids captured by the Spitzer Space Telescope to learn what rocky minerals are present on their surfaces. Martin co-leads a sub-team on the mission that will be using the James Webb Space Telescope to observe the Lucy targets once it is launched (currently expected to be Dec. 22).

“Working with the Lucy mission’s science team is so exciting and unreal,” Martin said. “Being invited to the launch was an amazing privilege, and something not many graduate students can participate in. The launch itself was indescribable! I am so looking forward to continue working with the Lucy team on this amazing mission.”

One of the primary goals of the Lucy mission is figuring out where Trojan asteroids were originally formed. Martin said the observations Lucy sends back to Earth will demonstrate whether these bodies are more like the rocky asteroids of the inner solar system or the icy comets of the outer solar system. Trojans currently orbit the Sun at the same distance as Jupiter. There are more than 7,000 Trojan asteroids, which are located in two swarms—one 60 degrees in front of Jupiter in its orbit (named after Greek heroes from “The Iliad”) and one 60 degrees behind Jupiter (named after Trojan heroes from “The Iliad”).

“Our current understanding of the solar system suggests that the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) moved around a lot in the early stages of solar system history,” she said. “Learning where Trojans formed and how and when they were trapped in these regions is the best way to test whether this view for the history of the solar system is correct. The compositions determined by the working group that Professor Emery leads will be very important for distinguishing the formation locations of Trojans, and therefore the history of the solar system.”

Kerry Bennett | Office of the Vice President for Research