JJ Duke, an assistant professor in Northern Arizona University’s Department of Biological Sciences, is studying respiratory mechanics—the “how” of breathing. He wants to understand the underlying reasons why exercise ability and lung function, or breathing, in general are more difficult for adults who were born prematurely. His research suggests the problem may be smaller airways.

According to the World Health Organization, 10 to 12 percent of all live births are preterm (at or before 37 weeks). However, because of medical advances, this number likely will continue to increase. Preterm birth results in an underdeveloped cardiopulmonary system and can lead to lung deficiencies that continue into adulthood and decline further with age. Researchers have found that adult survivors of preterm birth may have an atypical physiology and are functioning with 20 to 25 percent less lung and exercise ability than their counterparts who were born at full term.

With a three-year R15 grant of more than $432,000 from the National Institutes of Health, Duke is studying the underlying causes of the reduction in lung function, as well as exercise ability, in adult survivors of preterm birth. This knowledge, he believes, will assist physicians in ensuring a correct diagnosis and course of treatment for those born prematurely and suffering from respiratory problems later in life.

Duke first became interested in this population while studying determinants, or causes, of pulmonary gas exchange efficiency as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oregon. Given that adult survivors of preterm birth have underdeveloped lungs, it seemed likely that their gas exchange—their bodies’ ability to get oxygen into the blood and carbon dioxide out of the blood—would be impaired.

“We found no differences in the gas exchange efficiency, meaning they had normal oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in their blood. The lungs were functioning just fine in that respect, which makes it unlikely that this is the cause of their lower exercise ability,” Duke said. “As I left my postdoc, I pivoted my focus to another area of the pulmonary system that could limit exercise ability—respiratory mechanics, which describes pressure, airflow and volume in the system. As a result of their underdeveloped lungs, these individuals may have impaired or altered respiratory mechanics.”

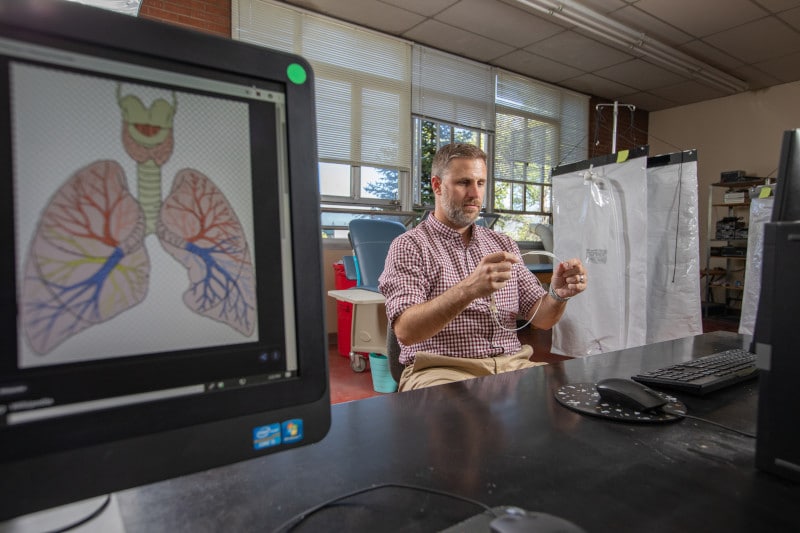

Duke is measuring various aspects of respiratory mechanics in the Integrative Cardiopulmonary Physiology Laboratory at NAU. To do so, he and his Ph.D. students measure esophageal pressure by having participants swallow a balloon catheter, then perform a variety of breathing tests and exercise on a stationary bike. The researchers measure the participants’ “work of breathing,” or how much energy they need to move air in and out of their lungs.

By conducting these studies, Duke can meet his objective to glean information about airway size in adults who were born prematurely by measuring esophageal pressure.

“If you are drinking a milkshake through a large straw, it’s easier to get it through that big tube than with a small straw,” he said. “Similarly, if airways are smaller, there is more resistance and you have to generate enough pressure to force the air through the airways.”

Because these individuals have never known anything different, they may not know it is more work for them to breathe during exercise.

“What is really compelling me to try to understand how the physiology is, and isn’t, different from people born at term is to help clinicians accurately target the problem and direct treatment,” Duke said. “Most of the time, people are aware that they were born prematurely but may not be aware that they may be more limited than their peers who were carried to term. If they report asthma-like symptoms, including chest tightness, they could be misdiagnosed and given a rescue inhaler, which might or might not help.”

Normal lung function decreases after the age of about 25 in healthy adults; however, by eating well, exercising and not smoking, Duke says most people should outlive their lungs. But those who were born preterm and are operating with 20 or 30 percent less lung function in the prime of their life may experience a displaced or steeper downward slope.

“Understanding the physiology of young people who were born prematurely, who do not have significant current lung function and exercise ability issues, is critical,” Duke said. “This research will help further the understanding of the physiology of adult survivors of preterm birth and identify potential targets for therapeutic interventions to improve and/or maintain cardiopulmonary function.”

Bonnie Stevens and Kerry Bennett | Office of the Vice President for Research