*Editor’s Note: The “Views from NAU” blog series highlights the thoughts of different people affiliated with NAU, including faculty members sharing opinions or research in their areas of expertise. The views expressed reflect the authors’ own personal perspectives.

By Monica Brown

Professor, Department of English

Dr. Brown who studies Latinx, African American and U.S. multi-ethnic literature. In addition to multiple scholarly books and book chapters, she has written many children’s books, both fiction and nonfiction. She authored “Side by Side: The Story of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez/Lado a Lado la historia de Dolores Huerta and César Chavez” and co-authored “She Persisted: Dolores Huerta” with Chelsea Clinton.

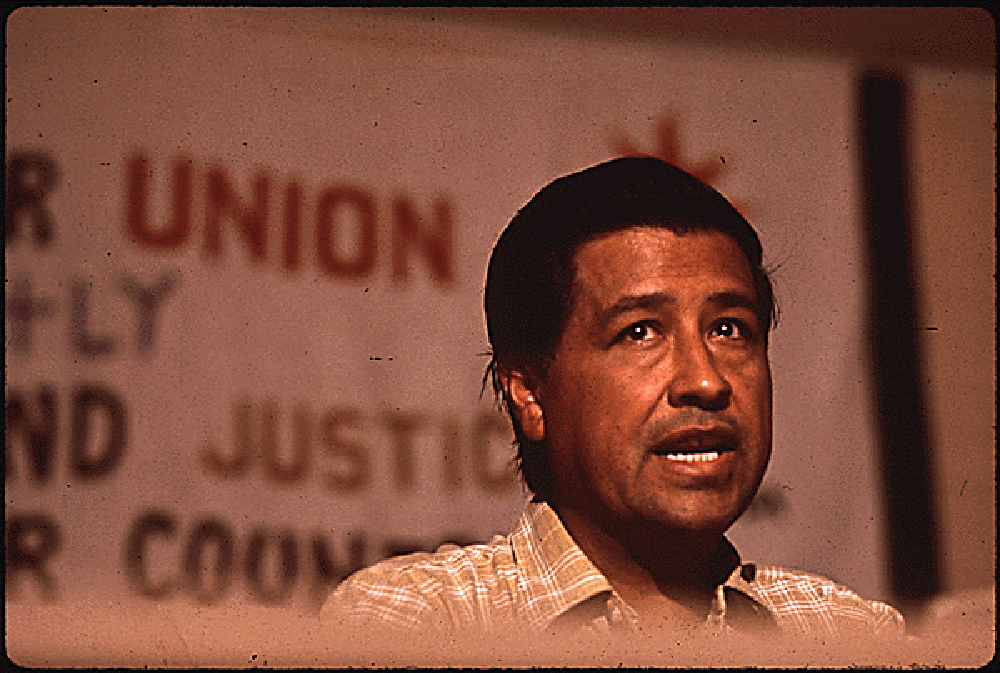

On March 31, César Chavez’s birthday, we honor his legacy as a labor leader and civil rights hero, a man who dedicated his life to social justice through community organizing and advocacy on behalf of farm workers. I think it appropriate that we celebrate César Chavez Day at the end of Women’s History Month, given his long partnership with another great labor leader, Dolores Huerta, whom he credited with being the co-architect of the United Farmworkers Association.

Having met Dolores Huerta for the first time when she spoke here at Northern Arizona University, I reached out to her when I was writing “Side by Side: The Story of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez/Lado a Lado la historia de Dolores Huerta and César Chavez”. She reviewed my manuscript and shared her feedback, calling César her “comrade.” I asked if she might share something directly about their work together, but she focused on only César’s accomplishments, noting his intelligence, hard work and belief in “helping people and reaching goals through non-violent and peaceful methods.” Yet historians and César himself have noted Dolores’s place alongside César in this journey. Even as César became the most public face of the union, they were a team.

Both César and Dolores were mentored by the great community organizer Fred Ross, who co-founded the Community Service Organization (CSO), a civil rights organization that fought discrimination and organized Mexican American communities to act together for change. When César first met Dolores, he was the CSO’s executive director and she a lobbyist for the same organization, working directly with state legislators. Most significantly, they were both dedicated to improving the lives of farmworkers. César and his wife, Helen (who herself had a great impact on the UFW), had both worked in the fields, just as Dolores’s father had. Their personal and familial experiences influenced their work.

Corporate farmers were powerful and clearly more interested in profit than people, using dangerous tools and spraying pesticides on the fields and directly on the workers, endangering their health. Farmworkers were in the fields from sunup to sundown, with little access to bathrooms and water despite often scorching heat. Furthermore, few farm workers had employment stability and had to follow the crops, which was hard on school-age children, who were pulled in and out of school regularly. César and Dolores shared a dream: organizing a farmworkers union so workers could bargain and negotiate with employerscollectively and gain power.

On March 31, 1962, César’s birthday, he resigned from the CSO and moved to Delano, California, in the Central Valley, where so many families suffered from exploitive practices by agribusinesses. Soon after, Dolores also left her stable position with the CSO and moved to Delano to organize. To make it work, she had to leave some of her children with relatives, and Dolores was so poor, she moved in with César, Helen and their eight children for a time. Dolores and César grew the organization by holding house meetings in workers’ homes to recruit them to la causa. They explained that the workers could be stronger together and asked for their help spreading the message. Soon this led to larger general meetings, and then, in 1963, they had the first NFWA constitutional convention in Fresno, California. César was named president and Dolores one of three vice-presidents.

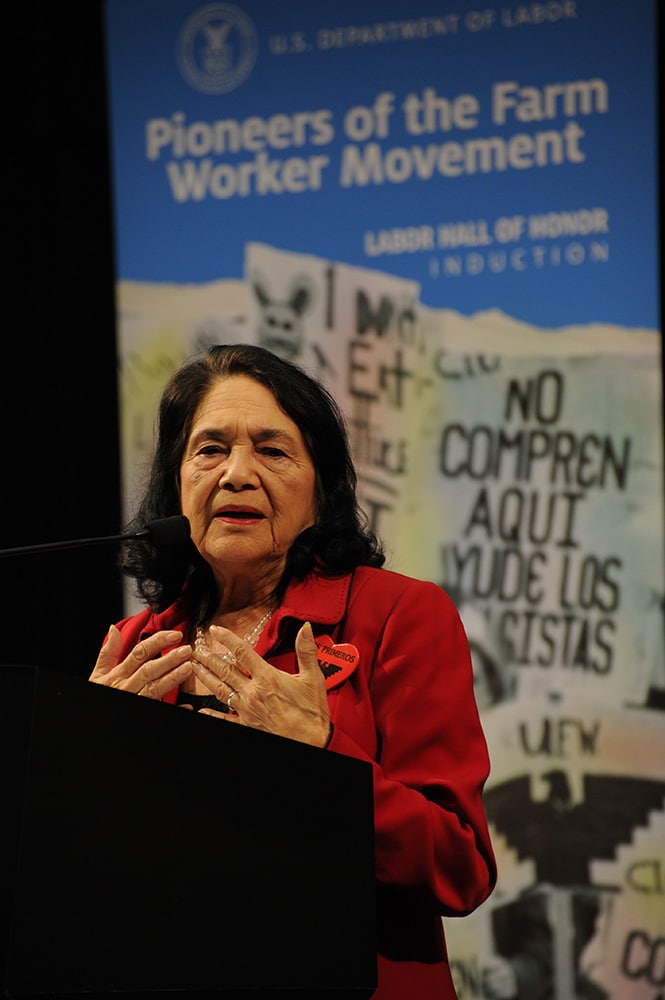

Though they often argued, César and Dolores had a great partnership. Dolores was nicknamed “la Pasionaria,” the passionate one. Despite their different styles, César valued Dolores’s honesty and insight, as she valued his. Using their complementary talents and skills, they had had many great victories, including the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, recognizing the right of farmworkers to bargain collectively in California. The United Farm Workers also led efforts to pass in 1986 the federal Immigration Reform and Control Act, which offered amnesty and legalization to millions of undocumented migrants who came into the United States prior to 1982. Farmworkers who could validate employment qualified for lawful permanent residency. Their work together in California influenced laws through the entire country and created better conditions for farmworkers and their families. It was here in Arizona that Dolores Huerta first said the famous words, “Sí se puede!” while speaking to a group of workers in Phoenix who kept saying, “We can’t organize the workers here. We can’t. No se puede!” Dolores responded, “Sí se puede! Yes you can!”

While working for the union, Dolores Huerta grew as a leader and as a feminist, advocating for equal rights for women. She was responsible for bringing many women into the labor movement. Although women had positions of great importance in the union, leading clinics and as field directors, the executive board members were all men in the early years—except for Dolores. As a board member, Dolores challenged discrimination against women in the union, and slowly educated her male colleagues about it. She was at the forefront of creating a more inclusive union. Together, César Chávez and Dolores Huerta celebrated many victories in their non-violent struggle for social justice.