*Editor’s Note: The “Views from NAU” blog series highlights the thoughts of different people affiliated with NAU, including faculty members sharing opinions or research in their areas of expertise. The views expressed reflect the authors’ own personal perspectives.

By Evan Martin-Casler

Executive board member of Black Student Union

For white-identifying students on NAU’s campus, or on that of any primarily white institution, it is a near certainty that, on the first day of classes, when they walk into a classroom listed on their schedule, they can look around the room and see a room filled with faces that could be cousins. In a room wherein they look ethnically similar to their classmates, they can put some trust in being seen for their ideas, interests, fashion sense or academic dedication.

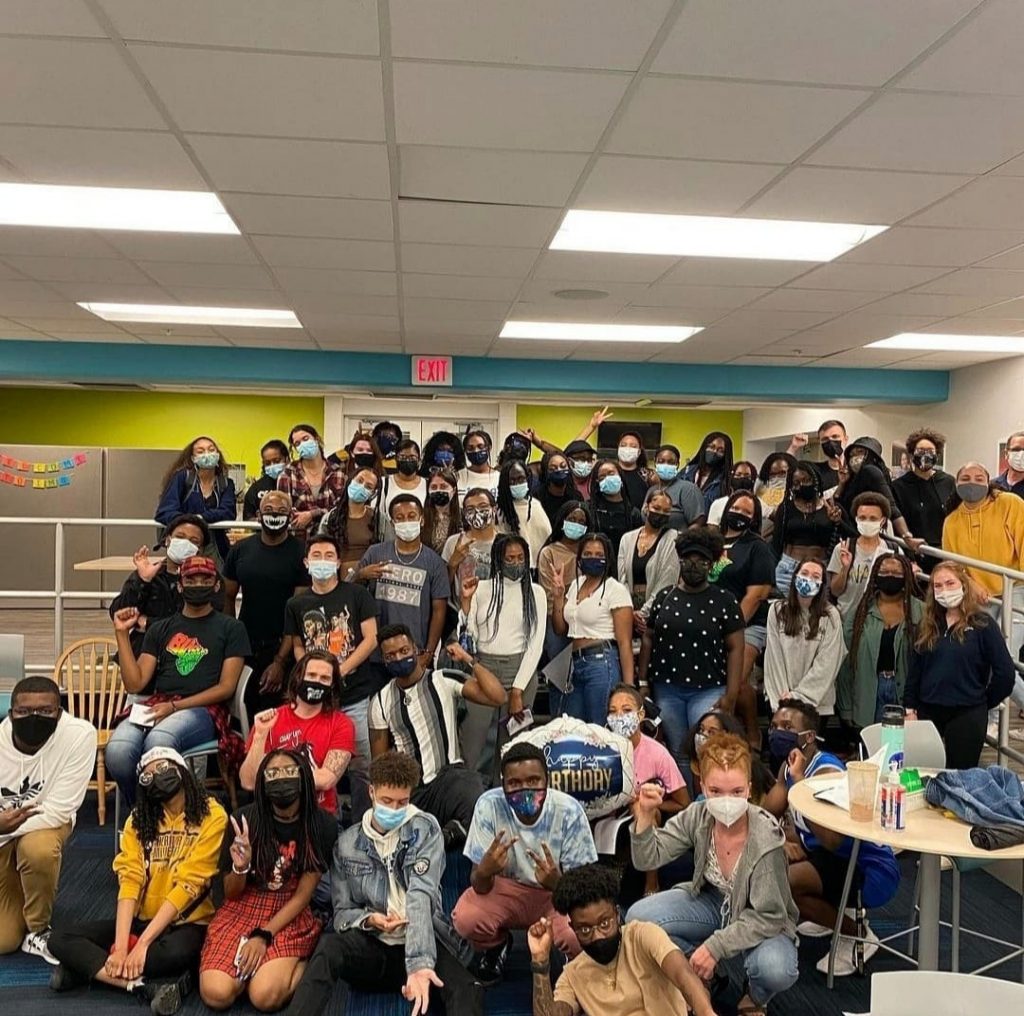

For Black students, on the other hand, the bi-weekly meetings of the Black Student Union may well offer the only hours in their week when they are not the only person in the room who looks like them—the only hours when they can set aside the sense of being perceived to represent the entire African Diaspora in classroom discussions and can, instead, be appreciated for their aptitude in their organic chemistry classes, sense of humor, warmth and compassion or their skills with an UNO deck.

It is telling that, when many of our club’s members invite their white roommates and friends to visit a meeting, they are met with the hesitant, “I don’t want to be the only white person there.” That anxiety about and aversion to the feelings of isolation and of being misunderstood should, at the very least, justify the existence of this and other important cultural clubs on our campus. Many students, upon attending a meeting for the first time, ask the other members, “Where have you all been? Where do you hang out?” and find themselves forming fast friendships that eventually feel like family.

While any person can surely understand the desire to feel included, understood, appreciated, and seen for something other than one’s appearance, it is easy to dismiss clubs that cater to only one aspect of a person’s identity. After all, the Black experience is not monolithic, and centering a club on the “Black experience” may sound to outsiders like a pigeonholing of infinitely complex individuals. On the contrary, nowhere is the diversity of Black identity more evident than in a room full of Black students, all of whom hail from different cities, states, countries and continents; all of whom have different tastes in music, movies, clothing and food; all of whom have different aspirations and worldviews. In a room like this, the world’s stereotypes are seen for the farce that they are, and instead of adapting to an educational institution that was founded, like so many others, with no consideration for eventual integration, students can dispense with code-switching, can take up space, can breathe.

As we enter into Black History Month—the very existence of which has long been met with bad-faith arguments like “When is White History Month?” and whose celebrated mainstays like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Ruby Bridges are newly being contested as the cultural propaganda of critical race theorists—it is crucial to recognize that there is no American history without Black history and, as important, that Black history is a living thing, terrifically complex and ever-growing. Black history is no more a thing of the past than the history of music or the history of philosophy. It is a simple thing to see that we are, today, living in times that will fill the history books of the future, and any of those volumes worth merit will acknowledge the dangers and the injustices and the victories and the innovations experienced by African Americans living now. While the term “unprecedented” is used hourly by news outlets to describe every aspect of life today, there is nothing unprecedented about the injustices experienced by people of color.

If we are to celebrate Black History Month—as well we should—by commemorating the victories of those who have passed before us, those who “fought the good fight,” those who experienced violence and hatred in their own time so we could polish their images and those of their contemporary detractors in the retelling of the story, we should not be so far-sighted that we fail to recognize the victories being fought for today, lest we become the bystanders in those history books of the future.

Justice, practiced at the most local level, is kindness, friendship and recognition of one’s own participation in the perpetuation of injustice. The last of these is challenging, but it can be as simple as developing an awareness of one’s cultural blind spots. It is not tautology to say that one does not know what one does not know, and if you are a white student who is hoping to develop a greater cultural literacy, a keener eye for injustice and a more comprehensive sense of humanity, consider stepping into the admittedly uncomfortable situation of being the “only white person in the room,” as I have chosen to do in attending Black Student Union meetings for the past three years, and allow yourself to learn some life lessons while making some lifelong friends.

And if you are a student of color who still has not found your home away from home, who still has not found a chosen family, who wonders “where everyone has been,” please consider attending a meeting or two. Your presence and your insights are valuable.

We have every right to be proud of the education that NAU provides, but one’s learning mustn’t exist solely within the classroom walls. After all, NAU is preparing young people to be citizens of the world. That requires an exposure to new ideas, an establishment of diverse connections and a development of a personal responsibility to better the world. If you find yourself looking around at your classmates, your teachers, your friends, your media role models and you find that they all look like you, ask yourself: On what brilliance and beauty am I missing out?