In August, Andrea Trujillo Lerner was preparing for the fall semester when she got an unexpected, ultimately life-changing call.

The call included an introduction—we’re the National Marrow Donation Program (NMDP)—and reminded her that more than a decade ago, she’d joined their donation registry and sent in a cheek swab. They had a patient with a life-threatening illness for whom she was a match. Was she still interested in donating stem cells?

The associate clinical professor of physical therapy didn’t even consider her answer.

“This is one of the easiest ways that you can help someone,” she said. “You can literally save their life, or be a part of that process, by just giving a small part of yourself.”

Now Trujillo Lerner is bringing the opportunity to be on the donor registry to NAU’s campus, hoping to get as many students, staff and faculty between the ages of 18 and 40 to sign up. Joining her are physical therapy students helping out as part of a service learning class and NAU alumna Aubrie Vargas, an account manager for NMDP who has her own reasons to be passionate about curing blood cancers and disorders.

“My hope is that we’re doing enough work now so that we can get people’s future donors on the registry,” Vargas said. “When these patients need a match, it may be their only hope for a cure.”

How to join the donor registry: Swing by the Union or the Dub between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. on March 25 to sign up and get your cheek swabbed. If you can’t make it in person, go to NMDP’s website to get a kit sent to you.

A donor’s story

Trujillo Lerner found out about marrow donation more than a decade ago, when her cousin was diagnosed with leukemia and needed cell therapy. She signed up with NMDP then, wanting to do something to help, even though she knew it was a long shot—being a match has a strong genetic component, and she and her cousin are not related by blood.

“What can I do to become a part of this?” Trujillo Lerner remembered thinking. “I want to be there for somebody else.”

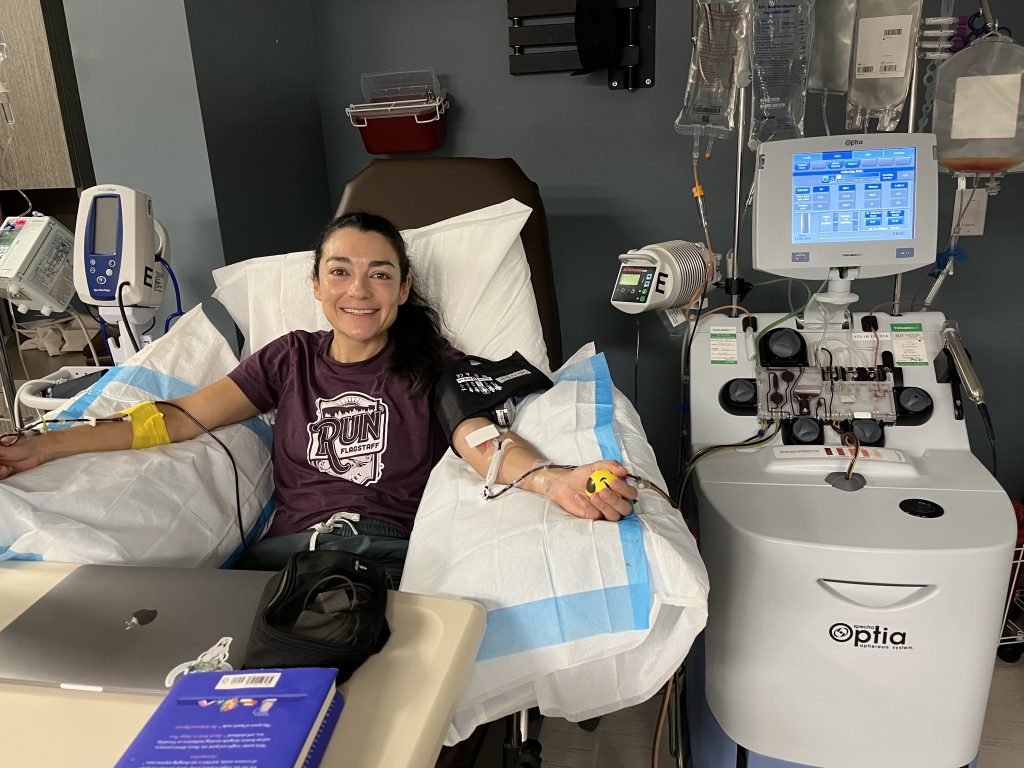

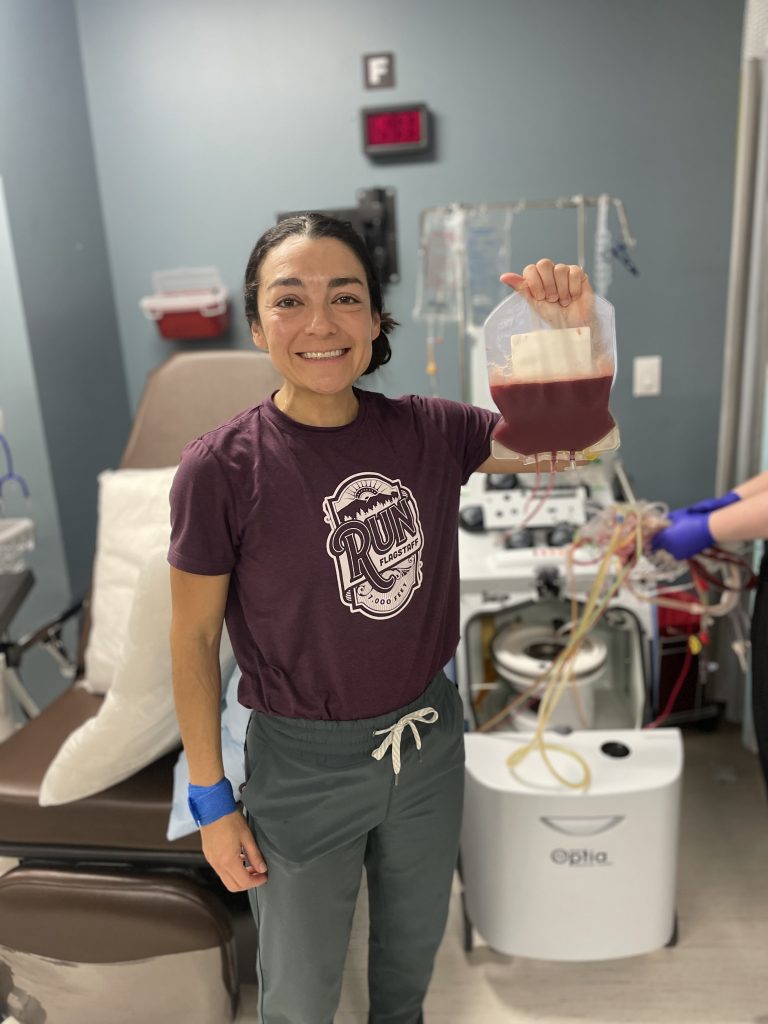

She also dispelled a common myth about stem cell or marrow donation: It’s really not painful. Her donation was of peripheral stem cells, which is about 90% of donations these days. She was hooked up to an apheresis machine, which is like having one IV in each arm (the same machine used to donate plasma); the blood was drawn, run through the machine to remove stem cells and pumped back into her body.

The other 10% is marrow donation, which does require anesthesia, but it’s a 30-minute outpatient procedure that leaves the donor a little sore—“it’s definitely not as bad as you have heard.”

Hear from recipients in NMDP’s “Where are they now” video.

What if you need a donor?

In 2002, Vargas was a senior at NAU, majoring in public relations while thinking about teaching, spending her free time playing volleyball and enjoying her college years. Then she got in a car accident and found herself with persistent back pain.

It happens after an accident, so she went to a chiropractor. But it kept getting worse until she lost feeling in her legs, so she got an MRI.

“I remember lying in the MRI machine, and in the little tech window I could see one person come in, and then three people came in, and I was having pretty severe pain at that point, and I knew something wasn’t right,” Vargas said.

That “something” was a mass the size of a softball wrapped around her spine, which a biopsy showed was cancerous. She had lymphoma. Almost immediately, she started a five-week round of radiation to shrink the tumor, then did 15 weeks of chemotherapy, then another five weeks of radiation. Depending on how those went, a bone marrow transplant was a possibility.

Vargas went into remission after that treatment and didn’t need the transplant, but the experience left her with profound gratitude for the people who made such treatment possible. If she ever relapses, that might be her only or best option. Knowing that strangers are willing to donate—that a stranger may be what saves a patient with lymphoma, leukemia or other blood disorders—motivated her to first volunteer, then work for the NMDP.

For 16 years, she has gone to events like this one at NAU, answering questions, dispelling that myth that donating marrow is difficult or painful and explaining to people the importance of having the widest possible variety of potential donors on the registry. She says it like this: You have a tissue twin in the world, and if your tissue twin ever needs you, by registering you’re saying, “don’t worry, I’ve got your back.” Maybe your tissue twin will never get sick, but if they do, you’re there.

So sign up, Vargas said. Spend five minutes, get in the registry, be there for your tissue twin.

“It’s difficult to find a donor,” she said. “There’s a misconception a lot of people have that there are tons of donors, so they don’t need my help, but we absolutely do. Even though we have about 39 million people on the registry, sometimes a patient may only have one donor match. It could be you.”

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu