March 27, 2019

A study published Wednesday in Nature used climate records dating back thousands of years to demonstrate that warming in the Arctic is associated with fewer storms and increased aridity in a huge swath of the Northern Hemisphere, including most of the continental United States. This pattern could lead to dramatic effects on agriculture and population centers throughout the U.S., Europe and Asia.

Assistant research professor Cody Routson, assistant professor Nick McKay, Regents professor Darrell Kaufman and postdoctoral scholar Michael Erb, all in the School of Earth and Sustainability at Northern Arizona University, led the study, which used newly compiled data from the Holocene Era (about the last 10,000 years) and compared it to simulations from global climate models.

“Future changes in drought and aridity will be among the most important impacts of climate change,” Routson said. “Our research suggests that the influence of enhanced Arctic warming will be another influence on drying, pushing vulnerable regions into drier conditions.”

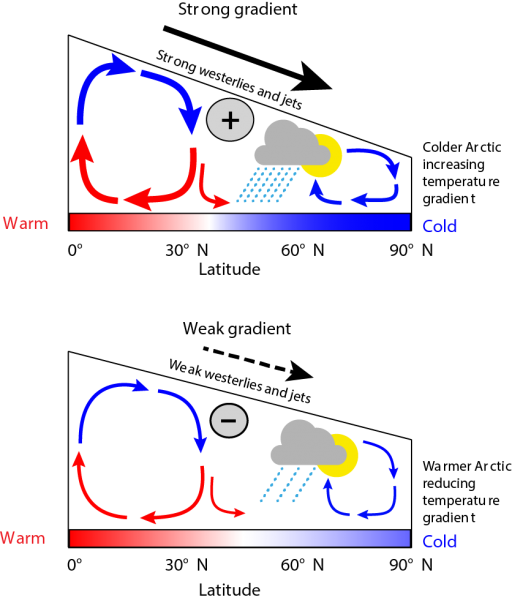

They hypothesized that this phenomenon—that magnified Arctic warming makes the temperature difference between the equator and pole weaker—could affect mid-latitude storm systems, which in turn affects farming and other food production in addition to water availability for population centers in arid and semi-arid regions. However, researchers only have direct observations of global climate change for the past 200 years, which is not long enough to test the hypothesis.

“By studying the geological evidence of past climate change, we could observe in retrospect how the Earth’s climate system responded the last time the Arctic warmed more than the rest of the planet, like it’s been doing since industrialization,” Kaufman said.

The study asserts that changing Earth’s energy balance affects circulation, storms and aridity.

The question of Arctic warming’s influence on the mid-latitude region came about as a mashup of several scientists’ different projects. Routson studied megadroughts in the Southwest and McKay was studying paleoclimate records throughout the Northern Hemisphere, with a special focus on the Arctic. They noticed a connection between Arctic temperatures and aridity in the mid-latitude region, which is approximately equidistant from the Equator and the North Pole, between 30 degrees north (runs through Houston and New Orleans) and 50 degrees north (runs through Vancouver Island and Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada).

“The Arctic has warmed more than low latitudes naturally in the past, which gave us a chance to investigate how a warmer Arctic influenced hemispheric circulation and rainfall patterns,” Routson said. “We compiled an unprecedented collection of Holocene climate records, extending a recently published collection of shorter records from the PAGES 2k project. We found that when the Arctic warms, resulting in smaller temperature differences between the Equator and the pole, the jet stream gets weaker and less precipitation falls in the mid-latitudes.”

What’s next?

This information will be useful as scientists evaluate the output of climate models that are now being run as part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s next major assessment report on climate change. The database of past climate changes also will factor into future research, both by NAU scientists and other climate scientists who are asking these types of research question. Kaufman said the team is looking for ways to combine this study with similar datasets from the Southern Hemisphere to get a global perspective and looking for regional details and mechanistic nuance.

The study, “Mid-latitude net precipitation decreased with Arctic warming during the Holocene,” was funded by the Science Foundation Arizona Bisgrove Award, the State of Arizona Technology and Research Initiative Fund and the National Science Foundation. It also is authored by Hugues Goosse from the Université Catholique de Louvain in Belgium; Bryan Shuman from the University of Wyoming, Laramie; Jessica Rodysill from the U.S. Geological Survey; and Toby Ault from Cornell University.