Modifying a behavior may not be as easy as upgrading an electrical fixture, but success on both counts could add up to millions in energy savings on a campus the size of Northern Arizona University.

The university committed in 2012 to making major changes in response to an audit by NORESCO, an energy services company, which found extensive opportunities to make campus a more sustainable operation. As the first phase of implementation nears its close, visible signs of progress abound and the cultural atmosphere seems open to making those steps count.

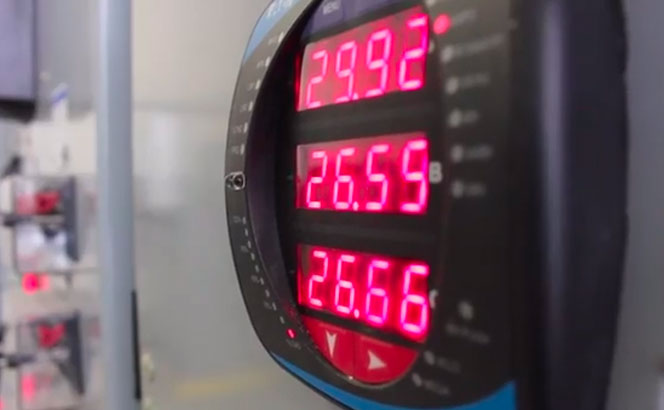

A tally of physical upgrades quickly produces big numbers: 28,000 lighting fixtures, 23,000 plumbing fixtures and digital controls for 26 buildings are among the changes. The intent is that their effective use will save more than $1 million in annual energy costs.

“I feel personally invested and proud,” said Jon Heitzinger, assistant director of NAU Utility Services who manages the upgrade project. He has faced the logistical challenges of working in dozens of buildings across campus and miles of tunnels beneath them, all while minimizing the impact on students, faculty and researchers.

The work put Heitzinger in touch with every building manager on campus and brought him face to face with people who can feel the difference of a new approach to energy management.

“The challenge, especially in older buildings, is to keep people comfortable,” Heitzinger said. “Before, there were no set standards. Now we try to maintain a range of 69-76 degrees. You can’t just set a steady temperature of 72 and be energy efficient.”

Outside the world of actuators and HVAC, others are advancing the quest to acclimate students, faculty and staff to sustainability NAU-style. Two program coordinators in Facility Services, Nick Koressel and Avi Henn, work daily to encourage behaviors that support the infrastructure changes. Through the Green NAU Energy Initiative, they meet with departments, create and place prompts, develop videos and do whatever else it takes to deliver a message of sustainability.

“Ultimately, the best thing we can ever achieve on campus is a cultural norm,” Koressel said. “Students are forming their identities and learning what it is to live on their own. They have open minds about learning new ideas.”

As Henn put it, “The bottom line for us is essentially changing habits, and to make these changes to the level of muscle memory—automatic.”

Turning off a surge protector, washing clothes in cold water, taking shorter showers and participating in recycling are actions that already come easily to some, but others take more persuasion.

By keeping the messages simple, Koressel and Henn try to “demystify” the process of achieving energy efficiency.

“We’ve all gotten those lists of 20 or 30 things you can do to reduce your impact on the environment, and it’s very overwhelming,” Henn said. “So we focus on only a few behaviors.”

While stickers and posters remind campus to “reduce the juice” or “strive for five,” it’s peer-to-peer interaction that effectively brings the messages home. More than 60 volunteer energy mentors among faculty and staff help reinforce the concepts in their departments.

Koressel and Henn interact with classrooms of students, where they’re found that “everybody’s got a different take on it,” according to Koressel. “But we’re not asking students to sacrifice—just to be more mindful of what they’re doing. Their actions can have a huge impact on water use and heating.”