Read this story in Spanish here.

Researcher Javier Ceja-Navarro has been a science communicator since he was a child.

“I have one younger brother, and to him, I was the encyclopedia,” said Ceja-Navarro, a professor of microbiology in the Department of Biological Sciences and the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society at Northern Arizona University. “He would ask me how things work. How everything worked,” said Ceja-Navarro, laughing. “’I need to study!’ I thought, so I can give him answers.”

So, Ceja-Navarro went to the small library in his town of Tuxpan, Nayarit, Mexico, read books, and came back ready to explain the answers he’d found to his brother.

Ceja-Navarro also was an avid artist as a kid—a skill he has continued to cultivate as part of his science communication practice. By the time he entered high school, Ceja-Navarro knew he wanted to be close to science. At the age of 15, he was awarded a scholarship to enter a high school track in clinical analyses, where he spent most of his time collecting all kinds of human samples to test for diseases.

“Many of the diseases we saw in my region are caused by protists, and it got me thinking: where did they come from?” Protists, a diverse group of one-celled micro-organisms found in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, include some infamous pathogens: Giardia lamblia, a common intestinal parasite, and Plasmodium, a large group of protists that cause the disease malaria in humans. “And wow, then I saw protists in soil,” Ceja-Navarro said. Intrigued, he learned to isolate them in the lab.

Ceja-Navarro also credits his mother for helping him learn to talk about his research with non-scientists.

“My mother was always super curious and read the books I read,” said Ceja-Navarro, who is a first-generation college student in chemical engineering and received a doctorate in biotechnology from Centro de Investigacion y de Estudios Avanzados del I.P.N in Mexico City. When he was preparing for his Ph.D. defense, he practiced his talk for his mother. “’No, no, no,’” he remembers her saying. “‘Explain it to me in a way that I can understand.’” So, he practiced and explained again.

When he joined Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in northern California as a postdoctoral scientist studying the insect-gut microbiome, Ceja-Navarro noticed that in his new department—where soil was the main topic of research—”everybody was talking about soil bacteria.” But he didn’t hear many questions about those protists he’d been thinking about since his days as technician in clinical analyses. “I thought: where are the protists, when protists eat pretty much everybody else?”

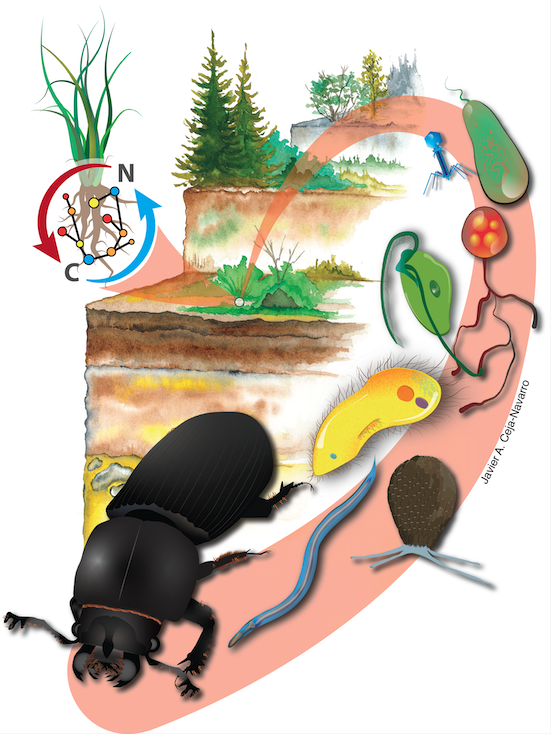

Expanding this conversation inspired Ceja-Navarro to study microbial food webs in soil and the often-complex relationships among microbes and the visible world. One relationship Navarro continues to decode is how microbes in the guts of insects allow certain insects to be “bioreactors.”

For instance, the coffee-borer beetle, Hypothenemus hampei, can consume lethal amounts of caffeine as it chews through its diet of coffee berries. Ceja-Navarro suspected the beetle was getting help from its associated microbes, and by sequencing its gut microbiome, narrowed the suspect list down to few bacteria, including Pseudomonas fulva. When he fed the beetle an antibiotic that killed off all the bacteria in its gut, Ceja-Navarro saw that the beetle could no longer digest caffeine or reproduce. When he added back P. fulva to the beetle’s guts, its coffee-absorbing superpower came back.

But Ceja-Navarro says that’s just one example of the holistic research approach he brings to NAU. He sees great potential in studying the microbiome as a complex system governed, like other food webs, by apex predators—often protists. And as one of the leaders of a new $3 million project from the Department of Energy, Ceja-Navarro and his colleagues at NAU and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory will be investigating who eats whom in soil, and how that chain influences critical biogeochemical processes like carbon and nitrogen cycling. “I want to make everybody excited about all the members of the soil microbiome, so we all take a whole-system perspective,” Ceja-Navarro said.

For him, that excitement begins with mentoring students. “I want to share with students my curiosity about our world, get them thinking about the little aspects of the world we don’t usually think about.”

He also wants to help more Latinos pursue science as a major and career.

“When I got to Berkeley Lab, I didn’t see many Latinos working in the laboratory,” Ceja-Navarro said. So he joined an outreach program, Science at Cal, in which university scientists visit local libraries and schools to host science conversations in Spanish. In northern Arizona, he hopes to share his science with Latino students and communities beyond campus, as well.

“As a Latino, I think it’s a responsibility of mine to share this excitement about science with other Latinos. My hope is to begin to ‘hear’ more Latinos in the laboratory, too, speaking Spanish.”

For Ceja-Navarro, kindling interest in science among students from all backgrounds is not only about education and career opportunities but strengthening the science itself. In his panoramic sense of what science can accomplish, bringing more people to the lab bench is an essential way for the field of microbial ecology to meaningfully solve the host of mysteries contained in a microbiome.

“A microbiome is a universe full of stars,” Ceja-Navarro said. “It’s that complex. Imagine being able to study each of those stars—think of all the things we could discover! Each one is waiting there for us to be curious.”