In the remote wilderness of the American West, where chainsaws and heavy machinery can’t go, fire may become the tool of choice. New research from NAU’s Ecological Restoration Institute published in Restoration Ecology shows that managed wildfires in these areas can help restore forest health and lower the risk of future severe fires.

As large, unnaturally severe wildfires become more common in the western United States—fueled by warming temperatures, increased drought conditions and decades of fire suppression—land managers have been exploring new strategies to restore forest resiliency and reduce risk.

Land managers are increasingly using naturally ignited fires, known also as resource objective fires, to achieve ecological goals. These fires offer a cost-effective, flexible approach, particularly in areas where mechanical treatments are restricted or impractical, such as designated wilderness.

“We know our current forest conditions are overly dense with too many trees, and that’s a problem,” said ERI researcher John Paul Roccaforte, the study’s lead author.

In 2012 and 2019, two lightning-ignited wildfires burned in the Mount Trumbull Wilderness, impacting a long-term study site monitored by ERI researchers. Managed by the Bureau of Land Management as resource objective wildfires, these fires were allowed to burn under supervision to restore forest structure and reduce hazardous fuels, rather than being immediately suppressed. This provided a rare opportunity to observe forest recovery under natural processes without mechanical thinning or other interventions.

“This is an incredibly remote wilderness area, and although fire is a natural part of the ecosystem, it hadn’t had a large fire in a long time,” Roccaforte said. “The fires were serendipitous for us because we could evaluate how they changed the landscape since we had long-term datasets and already knew historical fire patterns.”

Roccaforte’s research found that managed wildfires help reduce tree density, move forests closer to historical conditions, and likely lower the risk of future severe fires. Across the study plots, total tree density dropped by about half, canopy cover declined, and the average size of surviving trees increased. Historically, forests had roughly 25 trees per acre, but before the fires, these plots were crowded with nearly 500 trees per acre. After the two fires, density was cut in half to about 250 trees per acre.

Yet despite these improvements, tree density remained high—about six times greater than historical levels. To further restore the ecosystem and lower fire risk, Roccaforte recommends that land managers consider allowing more of these naturally ignited wildfires to burn in the future.

“We recommend managers allow lightning-caused fires to burn under the right conditions,” he said. “Restoration is an ongoing process that will require continued fire use to achieve ecological objectives.”

Nearly three decades ago, a team of ERI researchers, including Roccaforte, launched a long-term study in the Mount Trumbull Wilderness to understand how restoration treatments work at a landscape scale. Working with dozens of collaborators, the team evaluated forest structure, tree regeneration, old-tree mortality, and tree growth on the 5,244-acre ponderosa pine–Gambel oak forest. Today, this project stands as the longest-running landscape-scale restoration experiment in the Southwest.

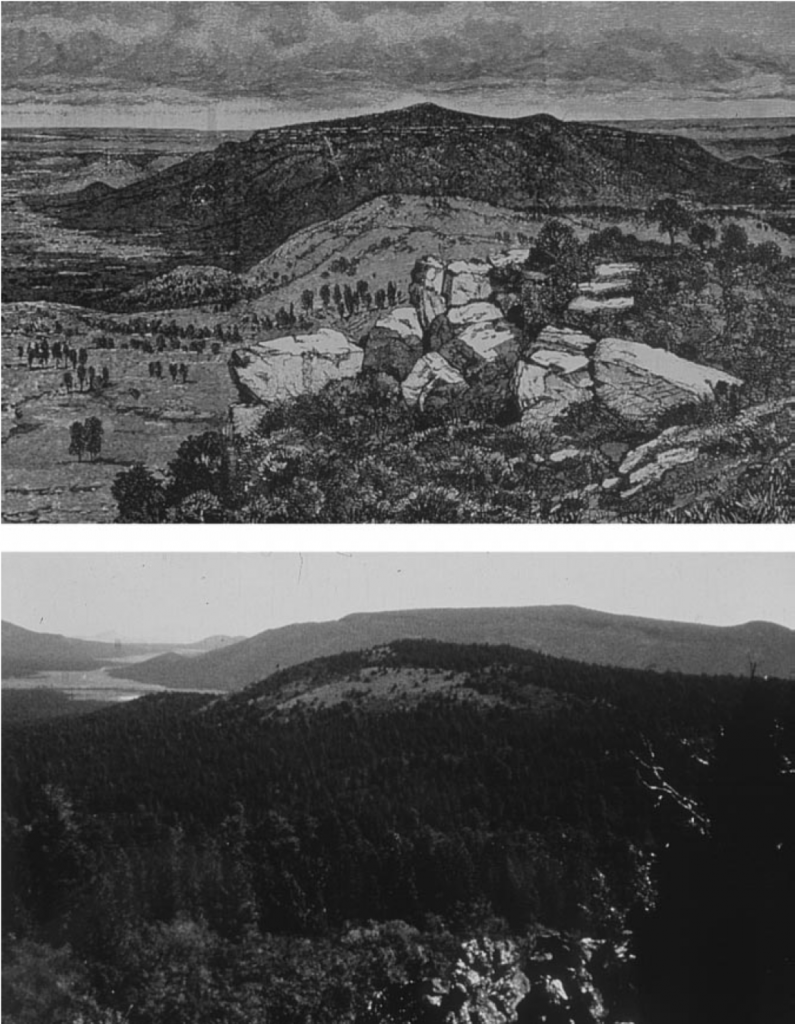

ERI began this long-term study of the Mount Trumbull Wilderness after noticing dramatic changes in forest conditions compared to historical landscapes. About 125 years after John Wesley Powell’s second expedition to the Grand Canyon, ERI photographed the same view Powell once saw. While the terrain looked familiar, widespread livestock grazing, early timber harvesting and decades of fire suppression had transformed open, large-tree forests into dense thickets of small trees with heavy surface fuels.

Mount Trumbull’s layered history explains these changes. For thousands of years, Native Americans maintained open forests through frequent, low-intensity fires ignited by lightning and cultural practices. After Euro-American settlement began around 1870, fire was largely excluded, and overcrowded forests developed. By 1999, the study area was dominated by closed-canopy stands of small-diameter ponderosa pines—vastly different from the open forests of the 19th century.

The resource objective wildfires at Mount Trumbull demonstrate the power of fire returning to the landscape. Remote sensing showed that areas burned in 2012 experienced reduced severity in the 2019 fire, illustrating how fire can be a self-limiting process. By reducing dense, overgrown forests and restoring historical conditions, these fires help limit the risk of high-intensity crown fires while supporting the ecological integrity of a federally designated wilderness area.

“These fires are showing us what restoration can look like in a wilderness setting,” Roccaforte said. “They’re reducing fuels, improving forest structure and setting the stage for more resilient ecosystems—but it’s a long-term process. Continued monitoring is key to understanding how these changes unfold over time.”

Jill Kimball | NAU Communications

(928) 523-2282 | jill.kimball@nau.edu