For most people, thoughts of death cause unease, discomfort or sadness. Not so, it seems, for Fabienne Sparks and many of her Gen Z peers.

“Every time I get into a car, I think, ‘This could be the one that finally does me in,’” Sparks wrote in a recent article for Kevin MD. “This used to scare me, but now I find it funny.”

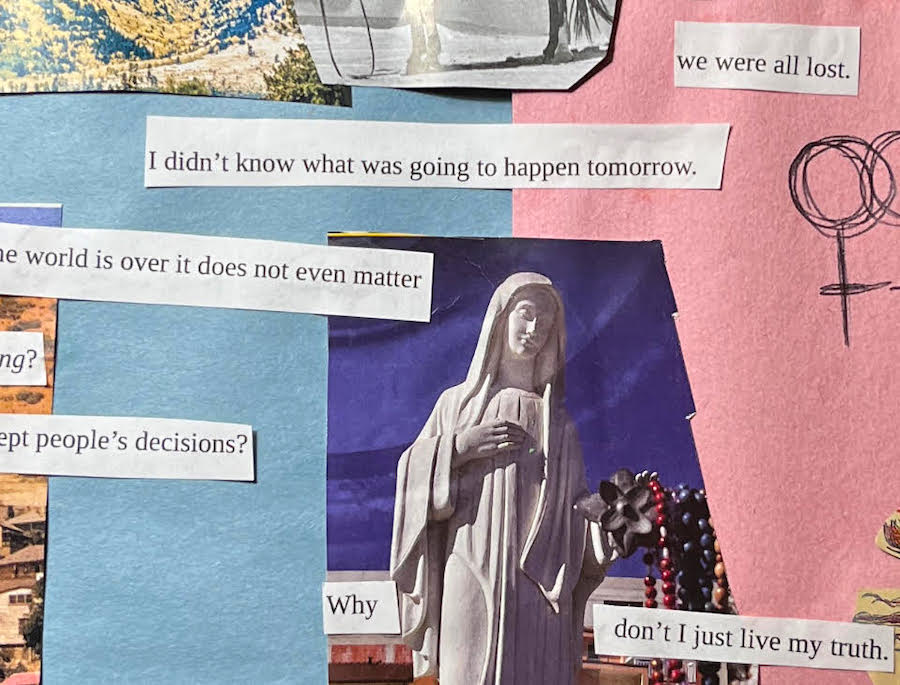

The NAU junior, who is studying anthropology, first realized she wasn’t alone when, in the first months of the pandemic, she saw an increase in social media memes poking fun at death. People posted stories about their minor inconveniences, like too much homework or bad weather, alongside a GIF of YouTuber Michael Stevens saying, “I have decided that I want to die.” An image of a sickly Victorian woman lying in bed, alongside the caption “When your alarm goes off and you have to go to work because you didn’t die in your sleep,” went (ahem) viral.

How did an overwhelming fear become something funny? Sparks has good reason to believe that for her and for other young people, experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic during such formative years of their lives shaped an unusual view of death.

As a student researcher in anthropology professor Lisa Hardy’s Social Science Community Engagement Story Lab, Sparks has helped conduct in-depth exploratory interviews aimed at understanding the sociocultural dimensions of COVID-19. When she joined the lab in 2023, she brought a new focus to the research: the pandemic’s effect on young people’s perceptions of death.

“In interviews, we hear young people talk about the inevitability of life’s end,” Sparks wrote. “Jude (a pseudonym) reflected on the death of a grandparent by saying, ‘I mean, what do we expect? (laughs) Anyway, I’m good.’”

To other generations, using humor to process loss might seem insensitive or like a trivialization of the seriousness of death. But the researchers’ work shows it’s exactly the opposite: This seemingly lighthearted attitude may be a result of their exposure to overwhelming loss in their formative years, and using humor to process their shared trauma might actually be helping them.

“The pandemic intensified helplessness, intense grief and an inability to think of anything else but the situation of the world,” Sparks wrote. “Some young people talk about making peace with death and their own mortality; others turn to humor as a coping mechanism…this does not necessarily trivialize death—especially when it comes to the death of their loved ones. Youth accept death as a fact of life, but they still mourn.”

Sparks wasn’t the only student taking part in this research. Also part of the lab were graduate students Carly Thompson-Campitor and Christina Meeks and Taylor Schweikert, a junior majoring in women’s and gender studies.

Schweikert said she hopes takeaways from the lab’s in-depth interviews will inspire medical providers, parents, teachers and others to address loss head-on with young people, rather than shying away from the subject.

“I think it’s important that we as a society don’t brush the impacts of COVID under the rug for the sake of ‘getting back to normal,’” Schweikert said. “Young people whose childhoods and teenage years have been significantly uprooted and impacted by COVID need to be heard. We had to find unique and creative ways of staying connected with each other in the midst of working through feelings of loss, grief, fear, confusion and isolation, to name a few. While young people have different experiences and unique memories surrounding COVID, it’s important for them to be given the space to reflect on it together.”

Jill Kimball | NAU Communications

(928) 523-2282 | jill.kimball@nau.edu