Several NAU researchers contributed to the Fifth National Climate Assessment, a congressionally mandated report that marshals an expert consensus of research and opinion on the current state of climate change and makes it easy to read, understand and put to use in individual regions.

The report, which brings together scientists from throughout the country, provides the foundational research to support informed decision-making nationwide. It builds upon previous assessments and aims to advance an inclusive, diverse, sustainable process for communicating scientific knowledge to resource managers, elected officials and the general public. The report is broken out by sector and region to allow people to see what’s happening where they live.

Contributors from NAU are:

- Ann Marie Chischilly, vice president of the Office of Native American Initiatives, co-authored Chapter 28, “Southwest.”

- Nikki Cooley, director of the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals (ITEP), co-authored Chapter 15, “Human Health.”

- Kevin Gurney, professor in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems, co-authored Chapter 12, “Built Environment, Urban Systems, and Cities.”

- Ted Schuur, Regents’ professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (Ecoss), and Victor O. Leshyk, Ecoss science and art director, were technical contributors on Chapter 8, “Ecosystems, Ecosystem Services, and Biodiversity.”

Chischilly, who has co-authored other similar documents, used her experience as a water rights attorney for the Gila River Indian Community in her discussion of tribal water rights.

“The NCA5 is critical information for the entire globe to understand the state of climate change today,” she said. “It explains where we, as human beings, are in this journey of the climate changing and what we need to do to improve the climate markers for the next seven generations.”

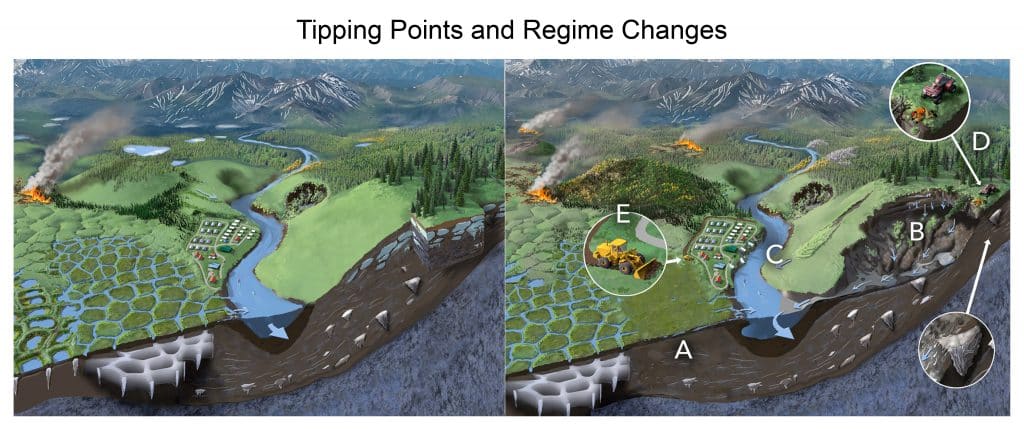

Schuur and Leshyk contributed diagrams about Arctic and boreal ecosystems that were reaching ecosystem tipping points, which Leshyk produced based on research done in Schuur’s and Regents’ professor Michelle Mack’s labs.

“Tipping points are very important for ecosystem dynamics because they imply there are thresholds that, once passed, cannot be taken back,” Schuur said. “Arctic and boreal ecosystems show this kind of behavior, and we have described these effects on permafrost, carbon, fire and forest change in dozens of peer-reviewed journal articles published by Ecoss scientists.”

Leshyk, whose focus is distilling science into graphics and making it understandable for a lay audience, said he and Schuur expanded previous artwork into “before and after” portraits of various landscapes to show what passing climate-driven tipping points would mean for the Arctic. The final product was bleak: it emphasized an increase in boreal forest fires, homes and villages sliding into the eroding banks of waterways and chasms opening in hillsides where permafrost has thawed and collapsed.

“As dramatic as it looks, what is not shown in my illustration is the most ominous change happening in the Arctic: all that thawing permafrost is exhaling astronomical amounts of greenhouse gases that immediately contribute to more warming, which makes for more climate-driven changes—not just in thawing permafrost, but around the globe as well, in a runaway feedback loop,” he said.

Gurney, who along with Schuur has contributed to other major climate reports like the IPCC, studies carbon cycle science and the built environment, which offers a direct link to humanity’s role in climate change.

“It is critical to regularly synthesize the large and complex literature and provide policymakers and the public a thorough account of what is and is not known about this problem,” he said. “The NCA offers geographic detail on the anticipated impacts of the changing climate, making it possible for local, state and national planning and policy to both enhance mitigation of climate changing gases and plan adaption to climate change to minimize the impacts.”

Cooley, who was part of the ITEP team that released the Status of Tribes and Climate Change report in 2021 and contributed to NCA4, shared her expertise as an Indigenous researcher in climate change, Indigenous and traditional knowledges and collaborating with tribes. Part of her focus was ensuring the chapter highlighted climate impacts on the most vulnerable and underserved populations.

“As a young Diné woman who grew up in a wonderful community that was rich in culture, knowledge and natural space, I was also exposed to a life that did not have access to running water, electricity and urban infrastructure and services,” she said. “It is important that the report continues to feature the voices and words of those who have direct experience with the unserved and unrepresented communities that are often on the front lines of experiencing impacts of climate change. Those voices are only marginalized if they are not asked to participate in some form.’

The NCA5 has one of the largest number of Indigenous authors spread out across the report, which is not an accident; Chischilly noted that they are disproportionately impacted by the effects of climate change.

“We hunt, fish, raise livestock, gather food, water and medicines directly from the places we live, so when we see dramatic changes in our lands, waters, plants and animals, it impacts us much greater,” she said. “I was raised on the Navajo Nation, and growing up, I would haul water and, wood, plant and, gather medicines and raise sheep and cattle. In my lifetime, the landscape has changed so dramatically that it is much more difficult to sustain and continue those traditions and lifeways.”

The work of many NAU scientists is referenced in the report as well.

Top image by Victor O. Leshyk: Thawing of permafrost can cause irreversible tipping points in Arctic landscapes, transforming intact ecosystems (left) to severely altered ones (right), with impacts on people. A warming climate and fires lead to melting ground ice. Arctic and boreal forests contain permafrost soils with excess ice (more than is contained in soil pores), which form 3D networks in the ground. With warming, this ground ice can melt and the ground surface collapses (A). Fires, a natural part of the boreal disturbance cycle, are increasing in extent, frequency, and severity. Melting ice can lead to the accumulation of water in ponds, lakes, and wetlands, but continued thawing can cause lakes to drain. Permafrost can also thaw abruptly, causing thaw slumps and bank failures (B). These geomorphological changes impact human infrastructure (C) and access to the land (D). Other risks (not pictured) include chemical and potentially disease mobilization that can threaten human health and ecosystems. Human adaptation strategies to permafrost thaw include installing firebreaks around infrastructure (E). Adapted from Schuur et al. 2022.

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu