A recent study that uses 3D satellite imagery collected by technology on the International Space Station found that worldwide protected forests have an additional 9.65 billion metric tons of carbon stored in their aboveground biomass compared to ecologically similar unprotected areas—a finding that quantifies just how important protected areas are in our continued climate mitigation efforts.

The study, published in Nature Communications by researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD), Northern Arizona University, University of Arizona, Conservation International and more, demonstrates the importance of protecting existing plant life, especially forests, in the global fight against climate change.

“This research is vitally important for documenting the value of protected areas, not only for the biodiversity benefits but also for the climate benefits provided by forests, which sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fix it into aboveground biomass,” said Scott Goetz, a Regents’ professor School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems at NAU and co-author of the study.

This study, which was jointly funded by the National Science Foundation (PI Brian Enquist, University of Arizona) and NASA (PI Laura Duncanson, UMD and Scott Goetz, NAU), used the highly accurate forest height, structure and surface elevation data produced by NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI, PI Ralph Dubayah, UMD, deputy PI Goetz of NAU).The team of researchers compared protected areas’ efficacy in avoiding emissions to the atmosphere with unprotected areas’ ability to do the same and tested the assumption that protected areas provide disproportionately more ecosystem services—including carbon storage and sequestration—than non-protected areas.

“

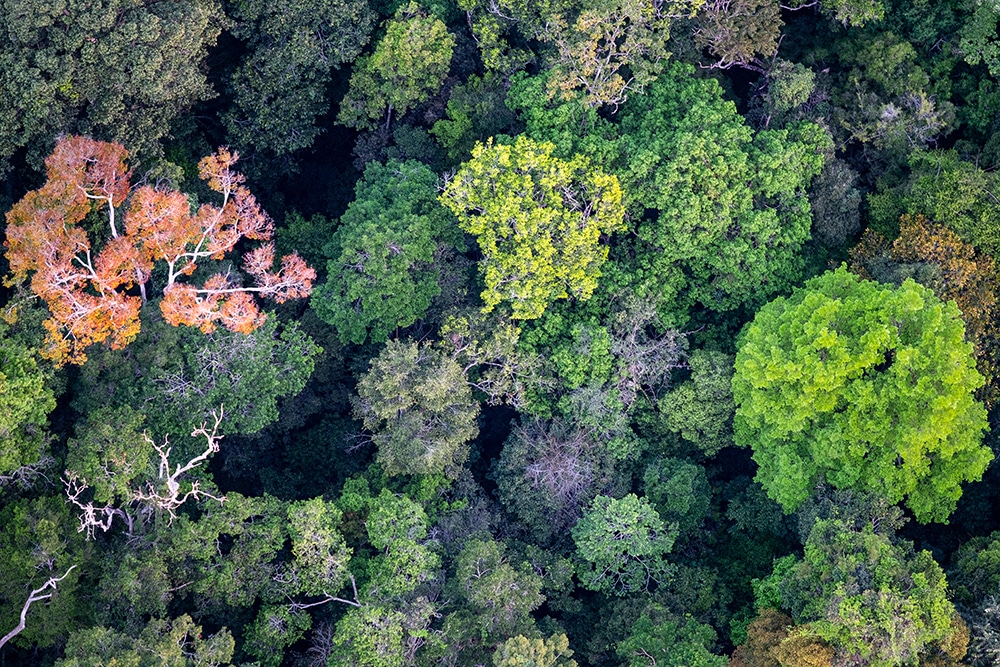

The biggest, most climate-positive impact the researchers observed came from the protected, moist broadleaf forest biome in the Brazilian Amazon, with Brazil contributing 36 percent to the global signal.

Another key finding was that the amount of aboveground biomass—the dry mass of woody matter in vegetation that stands above the ground—gained from protected areas is roughly equivalent to one year of annual global emissions from fossil fuels.

Previous attempts to quantify protected areas biomass content had high uncertainties and/or biases, as past satellite biomass products are known to saturate in high biomass forests, such as old-growth protected areas. GEDI data helped the researchers overcome these limitations.

The researchers specifically used height, cover, PAI (Plant Area Index) and AGBD (Above Ground Biomass Density) products from the first 18 months of GEDI mission data, which was collected between April 2019 and September 2020. In total, the researchers analyzed more than 400 million 3D structure samples and matched each protected area to ecologically similar unprotected areas based on climate, human pressure, land type, country and other factors.

“These results are novel in that they provide the first, long-anticipated evidence that protected areas are effectively sequestering a lot more CO2 from the atmosphere than otherwise similar but degraded areas that surround them,” Goetz said. “They were only possible because of systematic spaceborne measurements of canopy structure and aboveground biomass from the GEDI Lidar mission.”

The results also fit with the researchers’ hypothesis that forested protected areas had more carbon-capturing aboveground biomass not because of outright deforestation but rather by selective and illegal timber harvesting, small-scale agriculture and other, less overt actions that are destructive to the biomass.

The next phase in this important research will include assessing not only the carbon aspect but also quantifying the biodiversity benefits of these protected areas. Goetz hypothesized that protected areas would see more species richness and greater abundance of threatened and endangered species than their unprotected counterparts.

The study also highlights the urgency of protection and restoration for biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation, as emphasized by the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The IPCC found that nature-based solutions such as reducing the destruction of forests and other ecosystems, restoring them and improving the management of working lands, such as farms, are among the top five most effective strategies for mitigating carbon emissions by 2030

“Protected areas are an essential part of the conservation toolkit. They confer enormous benefits in the form of living carbon, essential to mitigate climate change’s worst effects,” said Patrick Roehrdanz, director of Climate Change and Biodiversity at Conservation International. “This research reflects the importance of the Convention on Biological Diversity target—of achieving 30 percent protection of all ecosystems—as an effective strategy to address more than one of the biggest environmental crises we face: biodiversity loss and climate change.”

Other collaborating researchers include Sebastien Costedoat, Patrick Roehrdanz and Alex Zvoleff (Conservation International); Brian Enquist (University of Arizona); Lola Fatoyinbo (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center); Mariano Gonzalez-Roglich (WCS Argentina); Cory Merow (University of Connecticut); and Karyn Tabor (University of Maryland, Baltimore County).

The full paper can be found at the Nature Communications website.

Top photo credit: Paulo Brando, Yale University