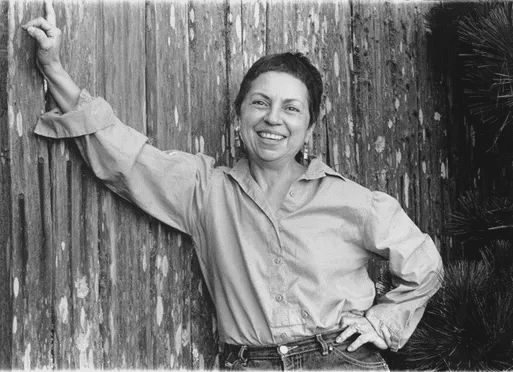

March is Women’s History Month, a time to recognize and honor the many contributions of women throughout history. The celebration is rooted in International Women’s Day, which has been observed on March 8 since the early 1900s to honor the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women throughout the world.

To celebrate the day, The NAU Review asked women of NAU to reflect on historical female figures who have impacted their life. Inspiring figures were nominated, ranging from Octavia Butler to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who embody environmental consciousness, cultural influences, equal representation, self-identity and equity. Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day serve as reminders of the ongoing struggle for gender equality and the progress that has been made. It also is a time to acknowledge the struggles and accomplishments of individual women throughout history and celebrate the ways in which they have shaped the world we live in today.

Through these reflections, these NAU women are not only telling their own stories but also the stories of the remarkable women who have paved the way for future generations.

Anne Franke (1929-1945)

In short, Anne changed the world by doing what she loved, despite her circumstances: writing about her experience in a vulnerable and authentic manner. In moving through my personal and professional identities, the ideas of vulnerability and authenticity have most shaped me. I find that these characteristics have allowed me to create trusting, meaningful relationships with others and understand that, from my belief system, this is the foundation of a life worth living. Further, Anne made what many of us would consider a bleak experience and environment, one that was enhanced by imagination, creativity, memory and connections to others. As a therapist, the ability to create meaning out of such limitations is a profound human gift. The strength captured in Anne’s writing has allowed me to understand that others who are suffering might also access their own gifts in order to find a path through. This understanding has allowed for increased empathy for and hope on behalf of those I support, whether as a friend, sister, partner, mother, therapist or in my role as dean of students.

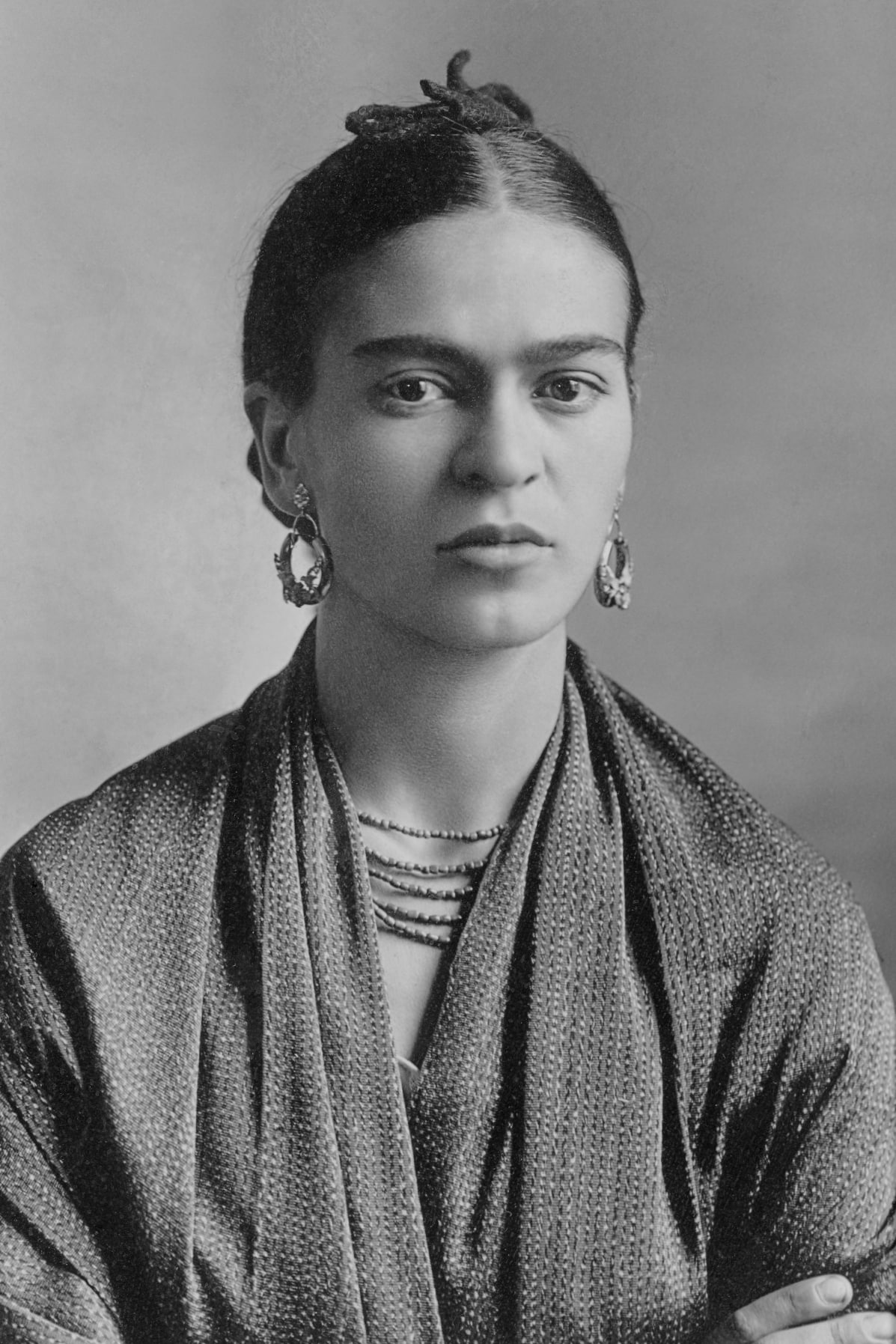

Gloria Anzaldua (1942-2004)

Many years later, Anzaldua continues to impact my teaching and scholarship. In my scholarly work, I seek to understand the experiences of Latina college students through a Chicana Feminist lens utilizing Anzaldua’s frameworks. In her later work, Anzaldua (2015) describes the path to conocimiento, a process of deep awareness that leads to “awakening, insights, understandings, realizations, courage and the motivation to engage in concrete ways with the potential to bring us into compassion interactions” (p. 19). The ultimate goals of conocimiento are healing and integration of the body-mind-spirit. This work inspired my dissertation and helped me and the Latina undergraduates who participated in my study to find healing in higher education. As a Chicana feminist, Anzaldua will forever shape my work. When I face challenges and need inspiration to keep going, I remind myself of one of my favorite Anzaldua quotes, “Do the work that matters. Vale la pena (it’s worth it).” Just as Anzaldua has helped me to feel more seen, I know it is important I continue to do work that helps others know that their lives and their stories matter.

Wilma Mankiller (1945-2010)

As a proud citizen of the Cherokee Nation myself, I have looked to Wilma as an incredible role model and inspirational leader over the years. I had the tremendous honor of actually meeting her in person at a conference in Phoenix years ago, where I also obtained a copy of her book, “Every Day is A Good Day: Reflections by Contemporary Indigenous Women.”

As she explains in her book, “Cherokee traditional identity is tied to both an individual and a collective determination to follow a good path, be responsible and loving and help one another – or as some Cherokee traditionists say, ‘Not let go of one another.’” The concept of Gadugi, or working collectively for the common good, is a vital attribute of Cherokee culture. Wilma certainly embodied this attribute, and I have tried to do the same.

Wilma’s resilient spirit has also been an inspiration to me, as reflected in this quote. “The question I am asked more frequently is why I remain such a positive person, after surviving breast cancer, lymphoma, dialysis, two kidney transplants and systemic myasthenia gravis. The answer is simple: I am Cherokee and I am a woman. No one knows better than I that every day is indeed a good day. How can I be anything but positive when I come from a tenacious, resilient people who keep moving forward with an eye toward the future even after enduring unspeakable hardship? How can I not be positive when I have lived longer than I ever dreamed possible and my life plays itself out in a supportive community of extended family and friends? There is so much to be thankful for.”

I, too, am thankful for some many things – my beautiful family, colleagues and friends who are always there to support me. And to strong Indigenous women such as Wilma Mankiller, who have paved the way for so many of us.

Doris Lessing (1919-2013)

Larry Armstrong, Los Angeles Times

For International Women’s History Month, I shine a spotlight on Doris Lessing, the British-Zimbabwean novelist and one of only 11 women to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Throughout her career, Lessing wove together the political, the psychological and the spiritual to convey and complicate the feminist experience. A child of colonial Rhodesia, Lessing drew upon her childhood in the African bush to denounce apartheid’s dispossession of black Africans and expose the banality of southern Africa’s white regimes. Her first novel, “The Grass is Singing,” takes place in Southern Rhodesia during the 1940s. It focuses on southern Africa’s racial politics between Whites and Blacks and grafts a personal story against the broader narrative of apartheid. Lessing’s subsequent semi-autobiographical novels, “Children of Violence,” trace Lessing’s rejection of traditional gender roles and involvement with (and eventual rejection of) the Communist party as a site of opposition and social justice. In 1956, in response to Lessing’s outspokenness, she was declared a prohibited alien in both what was then Southern Rhodesia and South Africa.

Lessing’s break through 1962 novel, “The Golden Notebook,” explored the inner lives of women and was described as a “handbook for a whole generation.” Scrutinizing relationships between men and women, she connected the fragmentation of personal with the fragmentation of society. Lessing expanded and pushed back against feminism in the 1970s and was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2007 for being “that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny.”

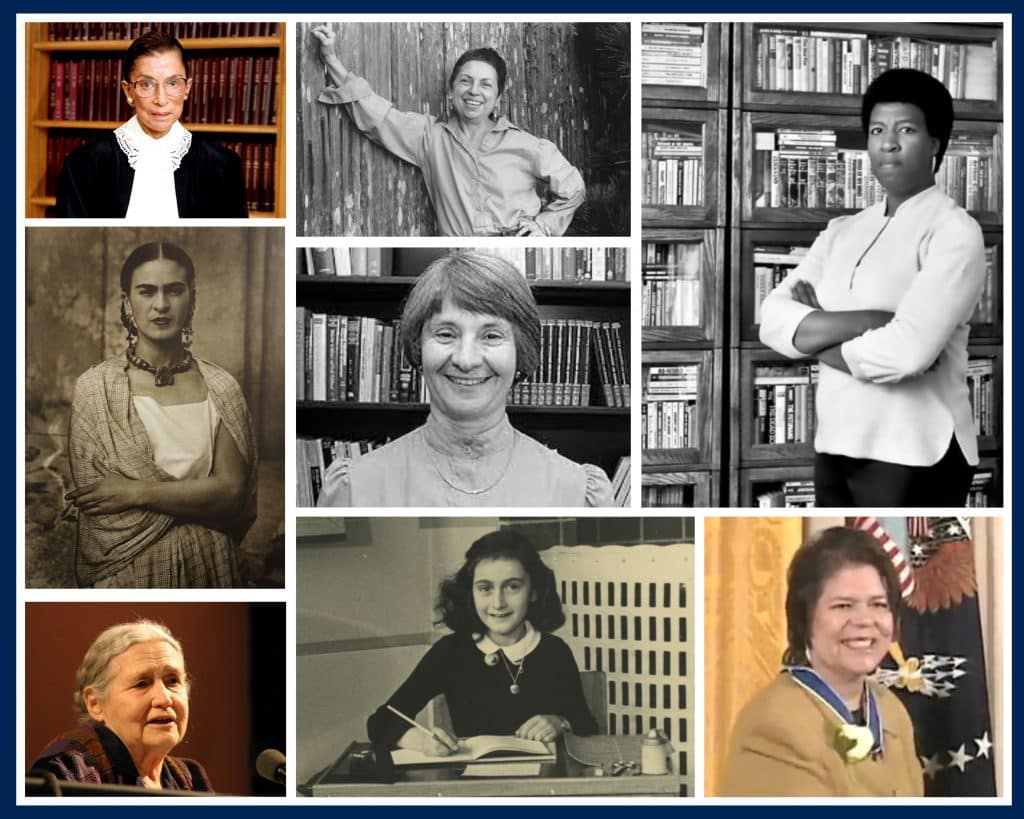

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020)

I didn’t grow up with the dream of becoming an economist, perhaps in part because it was hard to see myself in a role traditionally held by men. Ruth Bader Ginsburg influenced me well before she became a cultural icon. I was in middle school when she was appointed as the second woman on the U.S. Supreme Court. As a young student in the troubled and turbulent Durham, North Carolina public school system in the 80s and 90s, I saw firsthand the inequities of the justice system. Although the inequities made me feel outraged and disempowered, RBG’s approach resonated with me. I decided to learn as much as I could and use my knowledge to enact positive change. I spent high school and my first three years at the University of North Carolina on the pre-law track with the long-term goal of becoming a judge. I started college as an English major but soon realized I was drawn to economics. Although it certainly wasn’t the Harvard Law School of the 1950s that RBG experienced, women were vastly under-represented in Ph.D. programs in economics, even in the early 2000s. We still see the impacts today, with less than one in five professors of economics at the top Ph.D. granting institutions in the U.S. identifying as women.

RBG’s perseverance, quiet determination and willingness to play the long game continue to inspire me in my work. I deeply believe in the power of education to positively transform lives and that equitable access to education is a fundamental right for every person regardless of gender identity, socio-economic background, sexual preference, race or ethnicity. While I didn’t end up becoming a judge, my work as an economist provides unique opportunities to dismantle inequities. RBG continues to inspire me to think strategically, persevere through wins and losses and most of all, be human.

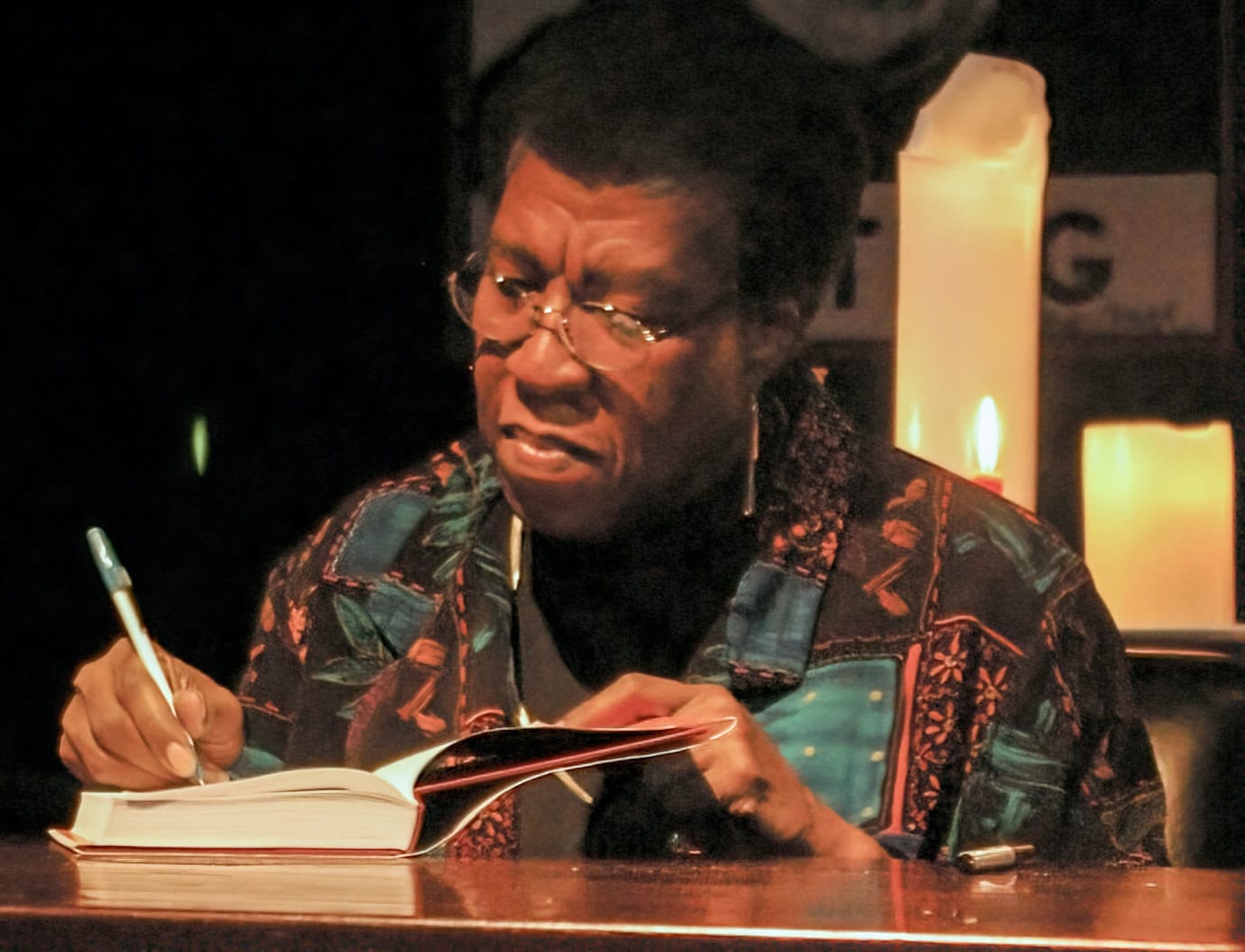

Octavia Butler (1947-2006)

“I began writing about power because I had so little,” Octavia Butler wrote in her journal. After her mother—who worked cleaning houses of the affluent in Los Angeles—gave her a typewriter for her eleventh birthday, Butler began crafting stories about future worlds beset by problems of power: segregation, poverty, illiteracy, environmental and racial injustice and wage slavery. Because her novels read like predictions come true, Butler is lauded for her uncanny ability to foretell the future; critics often call her work “prescient.” But she didn’t have special powers of divination. Instead, she looked around at the problems society neglected in the present, added 30 years, and imagined how they grew into full-fledged disasters.

Despite these dark themes, Butler’s dozens of short stories and twelve novels—including the wildly popular “Kindred” (1979) and “Parable of the Sower” (1993)—ring with hope for a collective future. In May of 2000, she told Essence magazine that “the one thing I and my characters never do when contemplating the future is give up hope … trying to look ahead and discern possibilities and offer warnings is in itself an act of hope.” Her most well-known characters—Lauren Olemina and Dana Franklin—are Black women who build alternate realities outside the stifling inequality of twentieth-century capitalism while navigating the ongoing legacies of colonialism, slavery and racism.

Butler was a vocal public advocate for public education. “Without the excellent, free public education … I might have found other things to do with my deferred dreams and stunted ambitions,” Butler explained. She read voraciously as a child, spending her free time in the Los Angeles Public Library, learning about geology, anthropology and history. Mars fascinated her, and in 2021, NASA named the Perseverance rover’s touchdown site on the red planet the “Octavia E. Butler’s Landing.”

Butler became a pioneer of science fiction and Afrofuturism. She was the first science fiction writer to win a MacArthur “Genius” fellowship and the first Black woman to win Hugo and Nebula awards. In 2000, she was recognized with a PEN Lifetime Achievement Award. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2021.

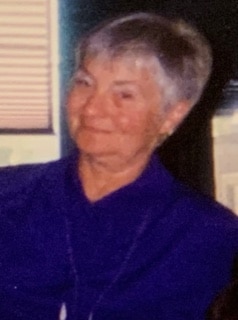

Carol Jacklin (1939-2011)

Carol grew up during a time when opportunities for women were extremely limited. After earning her Ph.D. in developmental psychology from Brown University in 1972, she dedicated her professional life to advocating for women and their rights. At Stanford University, she worked with Eleanor Maccoby and conducted observational research on parent-child interactions. Jacklin and Maccoby found that portrayals of women in the scientific literature were unduly negative. As a result, they investigated the published literature on the differences between men and women. They assessed more than 1600 articles and research papers and, in 1974, published the results of their investigation in the groundbreaking book “The Psychology of Sex Differences,” which argued that there was more variation within the sexes than between them. Not only was this book critically acclaimed, it became hugely popular among both academics and the general public. Highlighted on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, this academic text critiqued the existing psychological research methods at that time, was required reading in dozens of newly formed departments of women’s and gender studies, has been cited thousands of times and helped legitimize the study of gender and sex differences.

At USC, Carol Jacklin became the first-woman tenured professor of psychology, the first woman psychology department chair, the first chair of the Program for the Study of Women and Men in Society and the first woman Dean of Social Sciences. She made significant contributions to the fight for gender equity, testifying as an expert on gender issues against prominent companies and universities, with some cases reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. She encouraged the recruitment of female students and faculty and fought for the fair treatment of women in academia. In the late 1990s, Carol came to NAU and talked about her work for students and faculty. I was so fortunate to have known Carol and to have learned from her—she was not only passionate about her work and mission but also took time to learn new skills. After she retired, she became a master gardener and she was always, always, always, planning ways to get together with family and friends, preferably accompanied by travel, outdoor adventure, her beloved standard poodles and good food. Carol was an incredibly generous, supportive and a compassionate mentor—a woman who is worthy of remembrance for we have all benefitted from her outstanding and groundbreaking work that helped to expand women’s rights and opportunities.

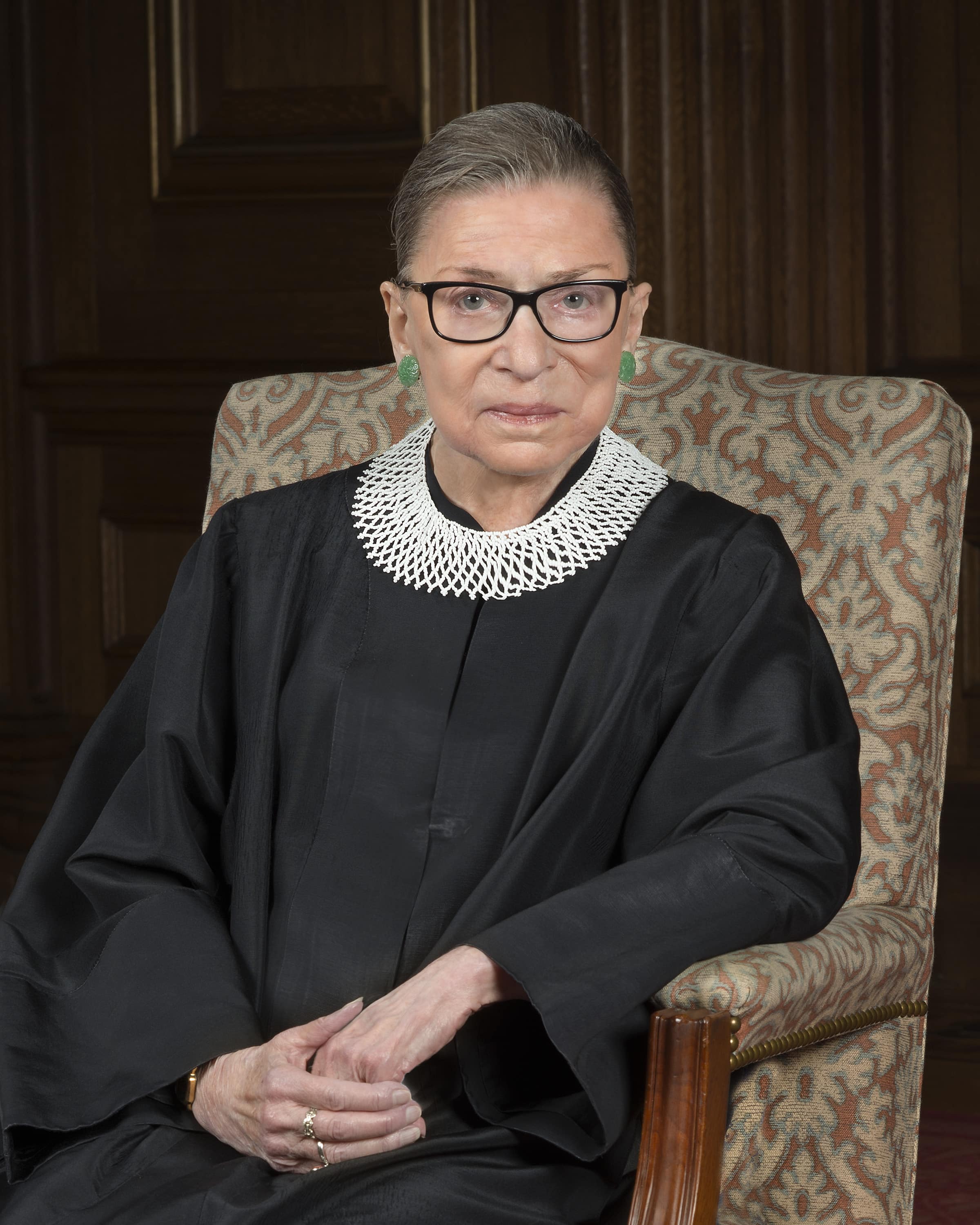

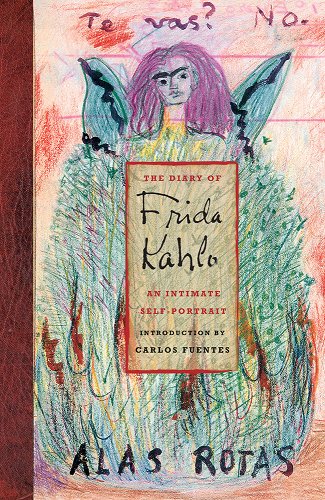

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

I celebrate Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón on International Women’s Day—and every day. Frida Kahlo—the artist, not the icon—has played an inspiring role in my life and that of my mother, Isabel Maria Brown, who was also a painter. Her art is a gift to all who struggle with illness in silence. Frida used her paintbrush to create beauty from pain, and to find strength in the midst of suffering. Frida Kahlo once said, “I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned to swim!” We are so lucky she poured her sorrows—and herself—onto canvasses and left the world with her art.

Frida Kahlo was born in 1907 at 247 Londres Street in the city of Coyoacán, which means place of Coyotes in Nahuatal, the language of the Aztecs. Frida, as she came to be called, was the daughter of a mestiza Mexican mother and a German-Hungarian father. Frida’s life was marked by many things, and among them were illness and pain. When Frida was only six, she contracted Polio, and in 1925, when she was only eighteen, she was in a terrible bus accident which left her with pain and health problems throughout her life. As a bedridden child, she made up an imaginary friend and had great adventures, and as an adult, it was during the long months after her accident that she took up painting seriously. Her subject was most often the face in the mirror—herself. She also painted her animals, who were her constant companions and muses.

To learn more about the Frida Kahlo—beyond pop culture’s representation—discover her published diary— it has been one of my constant companions and a source of strength and inspiration. It offers new and deeper insights into Frida’s brilliant mind and her passionate-, pain- and love-filled life.