*Editor’s Note: The “Views from NAU” blog series highlights the thoughts of different people affiliated with NAU, including faculty members sharing opinions or research in their areas of expertise. The views expressed reflect the authors’ own personal perspectives.

By Paul Helford

By Paul Helford

Teaching Professor, Creative Media and Film

Professor Helford has a lifetime of experience watching, writing about and educating students and community members about film. He teaches screenwriting, the art of cinema and film production and is the workshop director for the School of Communication.

In 2020, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (they give out the Oscars) established Global Movie Day for “film fans around the world to celebrate their favorite movies and engage with Academy members and filmmakers across social media… (and to explore) the power movies have to reach, connect and inspire people around the world.” This year’s celebration is on Feb. 11.

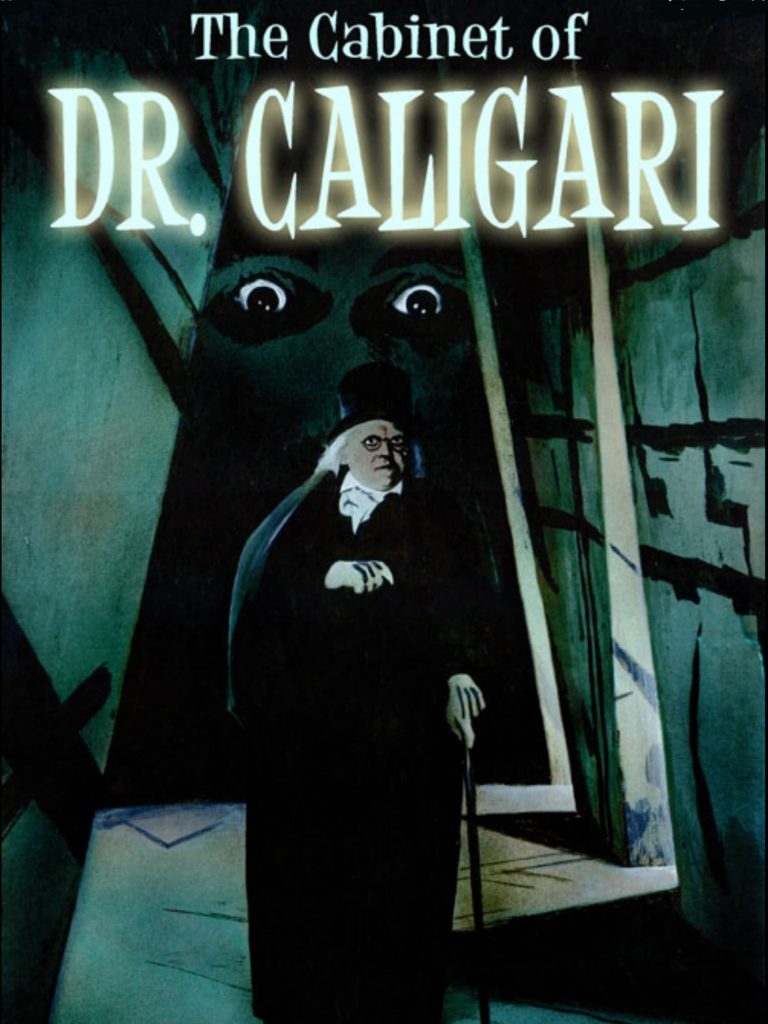

Movies have been a global medium since their inception. The first public performance is generally regarded as an 1895 showing in France by the Lumière Brothers, who astounded audiences with their single-shot, one-minute “actualities” like “Arrival of a Train.” Not long after, Georges Méliès, a French contemporary of the Lumières, produced more complex films that boasted early stop-motion special effects, as in 1902’s “A Trip to the Moon.”

From the Depression through World War II, while other nations’ film industries were devastated by world events, the American film industry thrived. After the war, American films, while popular worldwide, felt the weight of a censorious production code and competition from a little box people had in their homes called television. Meanwhile, around the world, film artists were making movies with adult themes that were becoming increasingly popular here.

Italy’s Neo-Realism movement often used non-actors moving through devastated Italian bombed-out locations in brilliant films like Roberto Rossellini’s “Rome, Open City” (1946), Vittorio De Sica’s “Bicycle Thieves” (1948) and Federico Fellini’s “La Strada,” (1954). Influenced by Neo-Realism and adding hand-held cameras, unscripted dialogue and long tracking shots to on-location shooting, the French New Wave movement sprung from a group of writers for the French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, which is where François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard began their careers. Their film debuts, Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” (1959) and Godard’s “Breathless” (1960), made a profound impact on cinema. The only French New Wave female director was Agnes Varda, whose distinctive, realistic neo-documentary films addressed women’s and other social issues, as in the marvelous “Cléo from 5-7” (1962).

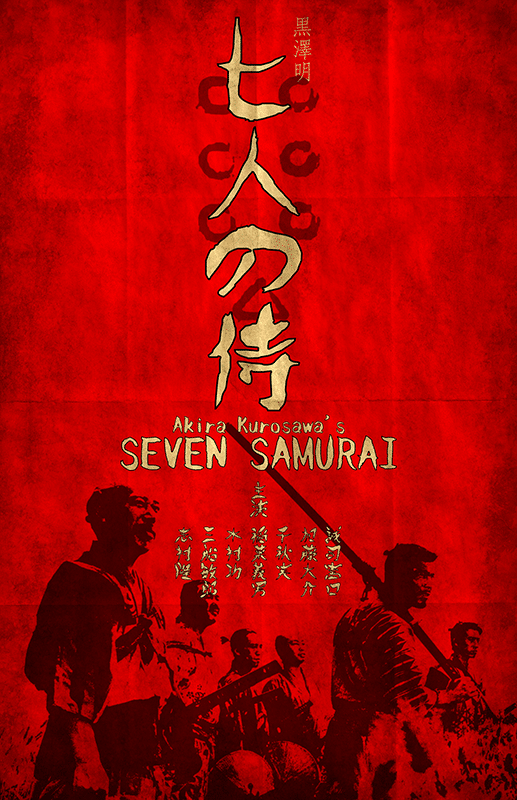

One of the most unique and influential filmmakers of that era was Swedish writer-director Ingmar Bergman, whose films, like

All the recommended Neo-Realism, New Wave, Bergman and Kurosawa titles are streaming on HBOMax and most, including “Fistful,” are rentals at Apple TV.

When I first discovered foreign films in the late 1960s, I’d find them in Chicago area art houses and revival theaters, my favorite of which was the Clark Theater in downtown Chicago, which had a new double feature every single day! Now when I visit L.A., I always try to go to a Laemmle theater, which programs independent and foreign films; the tagline is: “Not afraid of subtitles.” Which leads to my recommendation: Watch non-English language films with subtitles, not dubbed. You want to hear the original actors’ dialogue, most of which is recorded live. Besides, it seems everyone uses subtitles today. Netflix recently revealed that 40 percent of its global users have subtitles on all the time, while 80 percent switch them on at least once a month.

There are exceptions. Animated film dialogue is not recorded live. So, for me, films like 2022’s Danish animated documentary and triple Oscar nominee “Flee” (Streaming Hulu, rental at Apple TV) doesn’t suffer much from a well-done dubbed version. Nor do films like those by the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki (“Spirited Away,” “Howl’s Moving Castle,” and many others streaming at HBOMax), although I typically watch with subtitles.

Today, everything is right there in our TV rooms. The biggest lament I hear from other film lovers (and you’ve probably said it yourself) is that, there’s too much to choose from. To that end, I try to keep up with new films, American and other, as they are being released, but ultimately depend on each year’s Oscar nominees to help me sort through them.

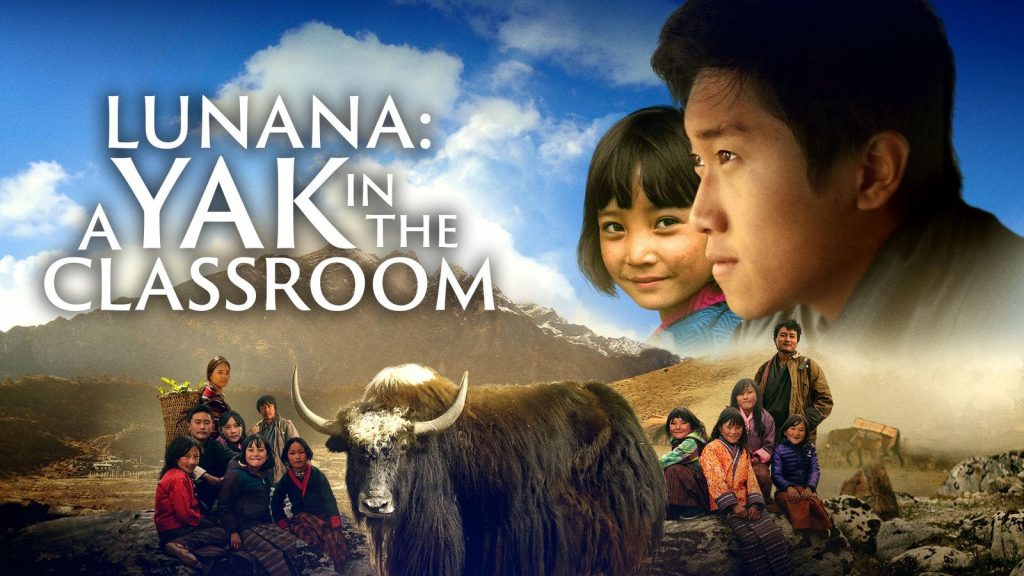

This year, I am most looking forward to non-English language Best Picture nominees, “All Quiet on the Western Front” (Netflix) and “Triangle of Sadness” (Apple TV rental). I’ll finish my Global Film Day recommendations with three favorites from last year’s Best International Film Oscar nominees: “Drive My Car,” a 3-hour Japanese film about a stage actor and his driver (HBOMax, Apple TV rental); “The Worst Person in the World,” a surprising Norwegian romantic comedy- drama (Hulu, Amazon and other rental); and a must- see for anyone who works in education, “Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom” (Apple TV rental), the first Bhutanese film to ever be nominated about a young man who fulfills his country’s mandatory teacher training in the most remote school in the world at an elevation of more than 11,000 feet in the town of Lunana.

By Paul Helford

By Paul Helford