As Arctic summers warm, Earth’s northern landscapes are changing. Using satellite images to track global tundra ecosystems over decades, a team of researchers finds the region has become greener as warmer air and soil temperatures lead to increased plant growth.

“The Arctic tundra is one of the coldest biomes on Earth, and it’s also one of the most rapidly warming,” said Logan Berner, assistant research professor with Northern Arizona University’s School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems (SICCS), who led the research in collaboration with scientists at eight other institutions in the United States, Canada, Finland and the United Kingdom. “This Arctic greening we see is really a bellwether of global climatic change—it’s this biome-scale response to rising air temperatures.”

The study, published this week in Nature Communications, is the first to measure vegetation changes across the Arctic tundra, from Alaska and Canada to Siberia, using satellite data from Landsat, a joint mission of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. Scientists use Landsat data to determine how much actively growing vegetation is on the ground—greening can represent plants growing more, becoming denser or shrubs encroaching on typical tundra grasses and moss.

When the tundra vegetation changes, it impacts not only the wildlife that depend on certain plants, but also the people who live in the region and depend on local ecosystems for food. While active plants will absorb more carbon from the atmosphere, the warming temperatures are also thawing permafrost, releasing greenhouse gasses. The research is part NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE), which aims to better understand how ecosystems are responding in these warming environments and its broader implications.

Berner and his colleagues, including SICCS faculty Patrick Jantz and Scott Goetz along with postdoctoral researcher Richard Massey and research associate Patrick Burns, used the Landsat data and additional calculations to estimate the peak greenness for a given year for each of 50,000 randomly selected sites across the tundra. Between 1985 and 2016, about 38 percent of the tundra sites across Alaska, Canada and western Eurasia showed greening. Only 3 percent showed the opposite browning effect, which would mean fewer actively growing plants.

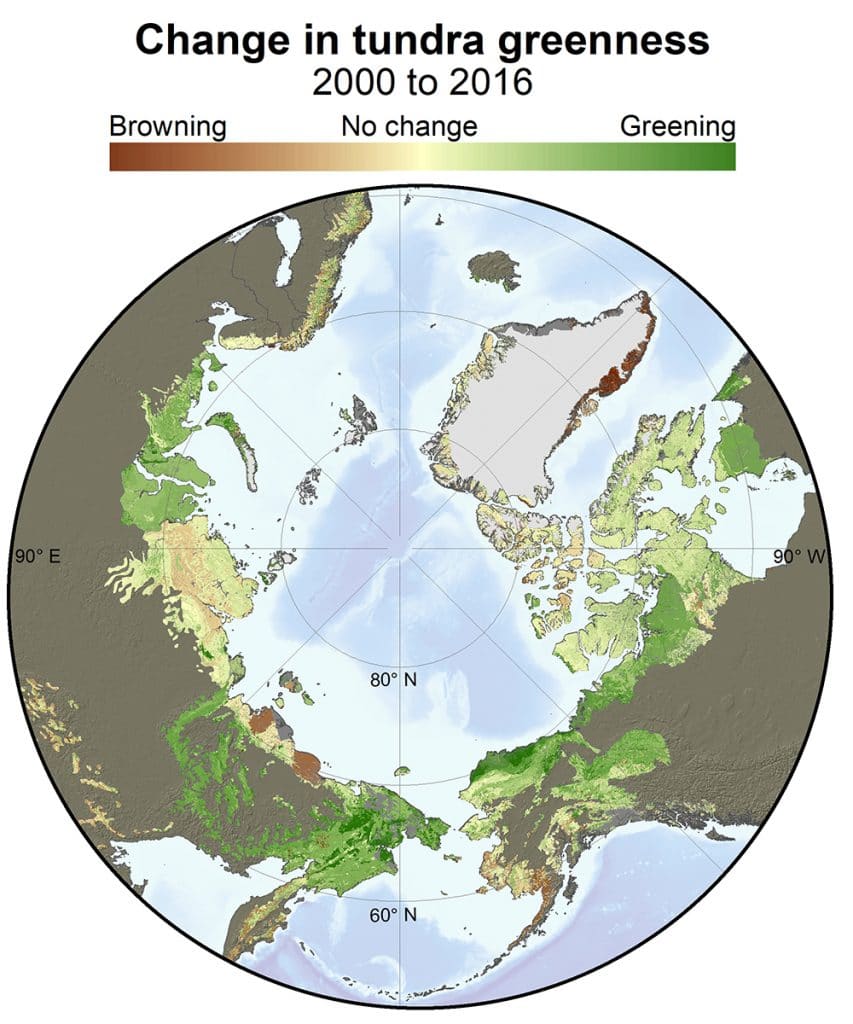

To include eastern Eurasian sites, the team compared data starting in 2000, which was when Landsat satellites began collecting regular images of that region. With this global view, 22 percent of sites greened between 2000 and 2016, while 4 percent browned.

“Whether it’s since 1985 or 2000, we see this greening of the Arctic evident in the Landsat record,” Berner said. “And we see this biome-scale greening over the same period as we see really rapid increases in summer air temperatures.”

The researchers compared these greening patterns with other factors and found that they are also associated with higher soil temperatures and higher soil moisture. They confirmed these findings with plant growth measurements from field sites around the Arctic.

“Landsat is key is for these kinds of measurements because it gathers data on a much finer scale than what was previously used,” said Goetz, who contributed to the study and leads the ABoVE science team. That allows the researchers to investigate what is driving the changes to the tundra. “There’s a lot of microscale variability in the Arctic, so it’s important to work at finer resolution while also having a long data record. That’s why Landsat’s so valuable.”

Kerry Bennett | Office of the Vice President for Research