Nov. 19, 2019

This summer, Wayne Nez’ office was Glen Canyon National Preserve.

Deon Eagleman’s was the White Mountains; his customers were teenagers looking for a future.

McKenna Parker’s was the Coconino National Forest.

The three Northern Arizona University students had unique summer jobs in 2019. They were part of the inaugural Weyerhaeuser Indigenous Conservation Crew (WICC), a program funded by timberland company Weyerhaeuser and the School of Forestry. It was designed to introduce students to a variety of career paths available in forestry and adjacent fields, encourage more Indigenous students to go into these industries and provide a good-paying summer job for students. By all accounts, it worked.

“This opportunity sealed my passion for working in natural resources,” said Parker, a junior studying forestry and a member of the Navajo Nation. “I come from generations of hard-working, independent women, so this field of work suits me well.”

The result was 12 weeks of manual labor that provided solid skills all of the students will use in classes and in their future careers, a nice salary for the 40-hour workweek and the opportunity to build relationships with industry and government partners, NAU professors and Native foresters throughout the country.

It also was an interpersonal and culturally enriching experience for the six of them.

“That’s what I really dug about the crew—we all come from different places, we all pretty much have one thing in mind,” said Eagleman, a junior forestry major, former wildland firefighter and father of a little girl who narrows down his Native lineage to Chippewa, Cree and Blackfeet on his father’s side and Apache on his mother’s. “We do appreciate getting a degree, we appreciate well-being for ourselves and our families, but we’re thinking about Mother Earth. We’re thinking about how can we get status to make changes and to be a powerful voice. In the land where mediocrity is accepted, we want to push that bar.”

How WICC started

Weyerhaeuser reached out to forestry educators at NAU earlier this year and invited them to apply for a grant, said Cheryl Miller, the manager of Centennial Forest. Facing a shortage of workers in the next decade as the boomer generation of foresters retired, the company wanted to invest in the next generation. They were particularly interested in NAU’s focus on bringing Indigenous students into forestry.

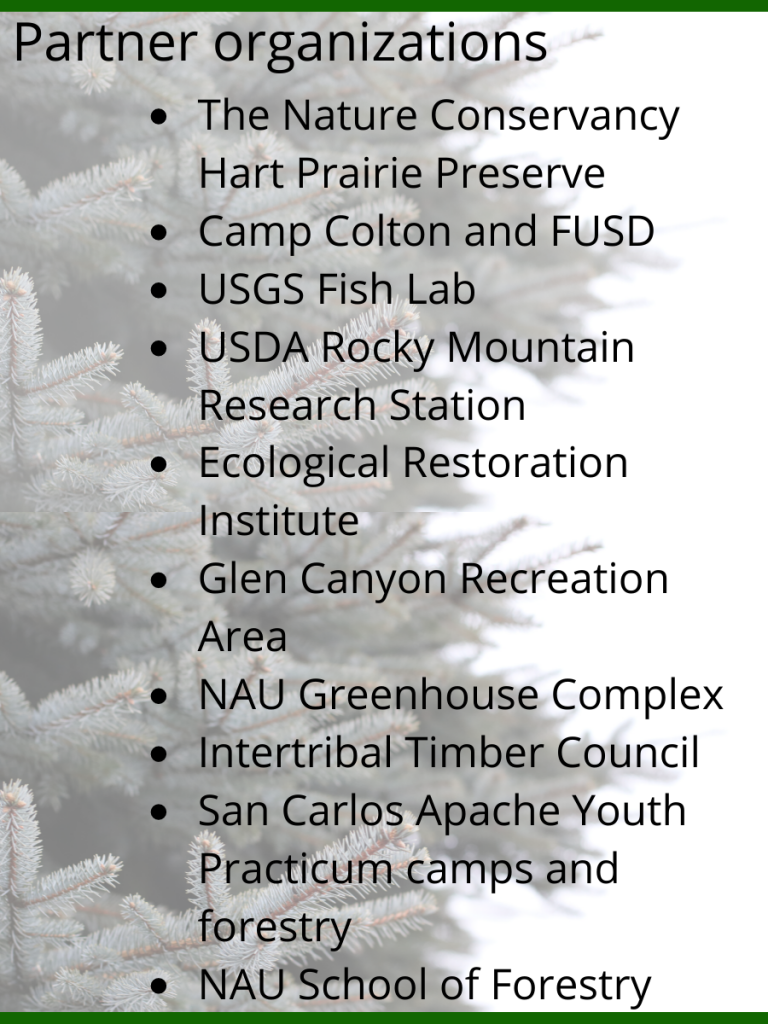

Miller, who runs Forest Friday in the Centennial Forest and is well-versed in hands-on forestry education, submitted a proposal that, upon approval, morphed into WICC. Weyerhaeuser donated $25,000, and the School of Forestry matched it. Miller hired a crew and started calling local conservation groups, federal agencies that work in forestry fields and NAU researchers, setting up weeklong work sites for the students.

“Forestry is a lot like being a doctor,” Miller said. “Once you get your degree you can do dozens of different things, and it’s really important in school to figure out exactly what you want to do. And you have to learn by doing. The students were able to get out and actually do things on the ground before choosing their career path.”

Miler wanted the crew to have a different assignment each week, so as she planned, she reached out to local nonprofits, local governments and agencies within the federal government, as well as her colleagues at NAU. The schedule she put together, although assignments got moved around and changed in order, had the crew doing manual labor, natural resources research, education and more.

The crew, led by Iliana Castro, who is working on a graduate certificate in geographic information systems, included Julio DeHose, a senior social work student and a member of the White Mountain Apache Tribe and Hawthorne Dukepoo, a sophomore forestry major, along with Parker, Nez and Eagleman, started their summer in the Centennial Forest. They did forest “cleanup”—clearing out dead trees and undergrowth, building trails, fixing up NAU’s field campus. From there, they moved to Camp Colton, which the Flagstaff Unified School District owns, and helped with their forest restoration curriculum by doing an inventory of trees, marking trees for removal and aging the trees that came down.

After that, they did forest restoration at the Hart Prairie Preserve, contributed to the School of Forestry’s chip and ship project at Camp Navajo, collected data in the area of the Museum Fire just before it broke out in late July, helped research crews capture bats and record data in Glen Canyon Recreation Area; built and stocked a fish pond for a USGS research project; and spent a night on the San Carlos Apache reservation, talking to teenagers about the opportunities available to them in forestry and, whether they intended to or not, acted as role models for kids with similar life experiences.

They also spent a few days at the Intertribal Timber Council in Florida, which offered the opportunity for the six Arizona students to meet tribal members from all over the world and learn about opportunities available to them.

Nez, a senior biology major, hotshot firefighter and a member of the Navajo Nation who’s interested in either medical school or a Ph.D. when he graduates, said his favorite experience was a tossup between working at Glen Canyon National Park and working with the U.S. Geological Survey. In Glen Canyon, the team helped rangers with bat monitoring; in return, rangers took the whole crew on a kayaking trip up to Antelope Canyon. They also helped a USGS ranger who studied the endangered humpback chub. This meant fishing for several hours a day, which Nez says with a smile.

“This really opened my eyes to natural resources research,” he said. “I was only familiar with lab-based research, and this opened my eyes to what’s going on in the natural resources realm.”

For Parker, it was her first time experiencing forestry work outside of the classroom. Not only did it cement her interest in a forestry career, it’s coming in handy in class. In one of her classes this semester, they went to Camp Colton for research.

The experience is likely to help all of them as they continue their education, about which Miller is glad. But the grant allowed her to make this work financially for the student as well. They got paid a generous wage for their hard labor.

“I want them to see themselves as an asset: ‘I have something to offer, and I should be compensated for that,’” she said.

Unique to Native students

Weyerhaeuser officials saw a real need to recruit diverse students into the industry, Miller said. NAU, with its focus on Native American education and outreach, was a natural fit. She then did her best to make the experience one that was uniquely valuable to Native students with their cultures and backgrounds, including ensuring they had the flexibility to participate in their tribal ceremonies and family activities throughout the summer.

“I tried to create an experience where they don’t have to choose one or the other,” Miller said. “They don’t have to choose education or their culture; they can keep a foot in both places and be strong in both places. I’ve learned that for them to be healthy and balanced and strong, they have to have both things. For us to ask them to choose one for the summer is to actually ask them to choose to be unhealthy, to disconnect themselves from what they need.”

The trip to the White Mountains to speak to high school students was particularly meaningful. Miller made the trip every summer, she said; she gave her spiel on forestry, she answered a few questions, she stayed in a hotel and she went home. She was a guest speaker. This summer, she sent the WICC students. They connected with the students, telling stories and experiences, staying after to play volleyball and eat dinner and stayed on the reservation. They were role models.

That was Eagleman’s favorite experience. He’s been through a lot, he said, and he wants to help other students get to where he is without as many detours along the way. He’s got full custody of his 9-year-old daughter and he’s working to finish the prerequisites he needs to get into an accelerated BS-MS program. Ultimately, he wants to get a Ph.D.

This experience was a perfect combination of his forestry and Applied Indigenous Studies work.

“A lot of the projects Cheryl put together had to do with traditional ecological knowledge,” Eagleman said. “Our bloodline is rooted deeper on this land than anybody else. What we’re trying to do is to have hope, to try to rise. I’m glad this conservation crew was put together because that’s being known. People asked for our help on their project because we get the work done, we’re dependable, we’re polite, we’re funny. We have our fun, but we also work really hard.”

Having similar backgrounds also helped the team bond, although they find plenty of differences to discuss as well.

“We were already basically on the same frequency,” Nez said. “The second day we were already all talking, already comfortable with each other. It was pretty diverse; we were from different tribes, so we were sharing our tribal knowledge. On our breaks, we’d be sitting down and asking each other, ‘what’s up with your tribal stories?’ ‘What do you guys do?’ It was culturally enriching.”

There’s no guarantee yet that there’ll be another crew next summer; it all depends on funding, Miller said, though she’s working on it. If it does happen, the 2019 crew has some suggestions for students who consider implying.

“If you’re not familiar with natural resources, learn all you can throughout the course of the program, especially if you’re not set on what you want to major in,” Nez said. “Apply and just take it for all it’s worth. If you have experience already, a program like this is a great way to get points of contact for possible employment, other internships and getting connected with researchers. That could open up pathways for graduate degrees or mentoring opportunities.”

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu