For most of us, seeing lions on an African safari would rank as the highlight of the trip, if not the year.

Seeing them defecate? Not so much. But that is the first moment Northern Arizona University wildlife geneticist Faith Walker recollects when she talks about her trip to Zambia in June.

Oh, and seeing a pride of lions take down a puku later that night was pretty cool, too. Two safari jeeps filled with NAU faculty and students sat quietly and watched the circle of life.

It wasn’t the typical study abroad or research experience, perhaps, but it was the trip of a lifetime.

Walker, along with School of Forestry professor Carol Chambers, led a group of students—four undergraduates and grad student Dan Sanchez—halfway around the world to experience what only Africa has to offer. They spent a week at Zikomo Safari Lodge near Mfuwe, outside South Luangwa National Park, exploring the park, doing non-invasive research on the wildlife and learning about Africa’s conservation history and challenges. Thanks to an NAU grant, they also got to donate school supplies to local schoolchildren and help with an unusual two-pronged economic development program in the village.

For Walker, who studies wildlife from the DNA they leave behind, the program was a chance to introduce students to a place she loved and did research early in her career while also increasing passion for wildlife conservation and global bridge-building.

“It seems like Africa gets under your skin and you never get it out, and you want to go back,” she said. “For me, it was really great to go back and bring a class that can experience Africa in terms of culture and wildlife. The wildlife is very much in need of protection, some species more than others. To see the elephants or the wild dogs or the leopards or lions in person, these charismatic megafauna, is a big deal, especially if you’re into wildlife and their conservation.”

Open-air classroom

Four students took the Wildlife Conservation and Management in Africa class, which Walker and Chambers co-taught; it culminated with their trip to Africa. The class met a few times throughout the spring semester, talking about the trip, their research and how to prepare, as well as writing papers and reading articles about conservation, wildlife management and poaching.

Then in June, they all boarded planes and flew halfway around the world, staying a couple of days in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, before taking a short flight to Mfuwe, then driving to the lodge about an hour away.

Their days started early—a 5 a.m. wake-up call, escorted to breakfast around a campfire at 5:30, then into the open-air jeeps for a wildlife game drive. They’d get back to the camp around lunchtime, eat, then use the heat of the day for research or discussion or to go into the nearby village, see the school and visit with the residents. One day they went on a walking safari, allowing them the opportunity to see details like tracks, plants and feces up close—or walking right up to a hyena, which they did, Walker said; the experience is very different on foot.

They returned to camp for tea—it’s all very English, Walker said—then, as the sun began to set and the day cooled off, back into the jeeps for another drive. They ate dinner late and were escorted back to their chalets, where they stayed until the next morning. No one could be out when it was dark.

And that curfew was strictly enforced at the camp, Walker said. The hyenas, leopards, hippos and lions who walked through camp did a good job of keeping everyone inside.

“A few nights later, when Dan and I missed the safari, a leopard came right by camp and we were unaware of it,” she said. “It was pretty exciting for the students on safari, because they knew where camp was and the leopard was going right to it.”

They had a couple of close encounters of the leopard kind. Tyler Tuengel, a senior forestry major from Glendale, said they saw a leopard hiding in the grasses one night and then lost it. Instead of looking through the tall grasses, Tuengel happened to glance up. The leopard was in a tree 15 feet in front of the jeep—well within its jumping distance, if anyone’s counting.

Another night, they caught a glimpse of a hunting leopard in the jeep’s headlights.

“The guide flashes his light and you see him, and the next time he flashes you don’t see him, and you’re like, where’d he go?” Tuengel said. “The next thing you know, he’s right at the side of the jeep.”

For Katy Henry, a senior biology major from Phoenix, the program was a great experience to prepare her for graduate school and her eventual career in wildlife conservation. Helping with the research, collecting samples and seeing animals in their natural habitat, along with the effects of poaching, which remains the largest threat to big game animals in Africa, all contributed to the hands-on learning she wanted. It was such a good experience that she didn’t even mind sharing a room with Alfonso, a wall spider the size of her hand.

“It’s always been a dream of mine to go to Africa and see the wildlife there, but also, the research techniques that we used were really helpful, and learning how to use them will be good in the future,” she said. “I would like to do this as a career—in Africa or anywhere. Africa would be really cool, but you can apply those techniques anywhere, so it was a good learning opportunity.”

Wildlife research

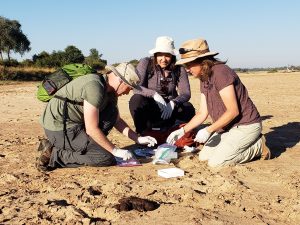

Walker, an assistant research professor in the School of Forestry and the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, used this trip to collect data on DNA collected from animal feces. Sequencing the DNA in feces of wildlife tells scientists what the animals are eating, what diseases they’re suffering from and even the basics of what animals are out there and how many of them there are. All of it helps conservation and population management.

That wasn’t her big research question this time around. She had a new handheld genetic sequencer that reads DNA in real time in the field on a laptop—a recent first for genetics research, which usually requires a laboratory and much larger machine. This device allowed Walker and Sanchez to sequence the DNA in Zambia to identify the species that wildlife were eating, meaning they only needed to bring the data home with her, which is much easier to get through customs than lion poop.

Her goal this trip was to determine how accurate this smaller device was and how feasible it is to use on crappy DNA at a remote field site on the other side of the planet, using diet of large carnivores as a test case—a first for this technology. Before leaving Flagstaff, she and Sanchez tested it on fresh bobcat and jaguar feces, which Bearizona donated, while also using her lab-based sequencer, and got similar enough results that she trusted the portable sequencer. It still took some finagling to make it work, though.

See the online album for additional photos.

For instance, she didn’t know the program needed an uninterrupted 2-minute Internet signal to start running, nor did she know there was a standalone version available with special permissions until she was in Zambia trying to run the sequencer. She used WhatsApp to ask her genetics research specialist in the United States to call the company in England to get the standalone product. (All of this was happening on Friday night.) No one was answering. They were camped out in the safari camp’s office and the sun was going down and the rest of the group was on a night jeep ride when the sequencing finally started.

“Pretty soon it’s 12:30 at night, we don’t know if we can leave the computer or if Dan could take it to his room or if we had to stay up with it, and we were just watching the number of sequences grow until finally it’s getting to a number where I’m thinking, ‘OK, we can actually publish,” Walker said.

At about 1 a.m., as they were being escorted back to their chalets, having left the computer with a note to not turn it off, they heard the camp owner radio about a large hyena near her room. And the fun wasn’t even done.

“We knew there was a hyena out there, and then we walk right by this hippo,” she said. “It was just wild. We could hear the animals making sounds, the African night sounds, and then we walk by a giant hippo.”

Hippos, hyenas and hunting leopards aside, the sequencer worked. It’ll be returning to many more fields in the future.

“It was successful, although we learned a lot about what we need to do to make this really efficient,” Walker said. “We’ll be publishing that in the next couple of months.”

Crystal Hepp, an assistant professor in the School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Security, also went on the trip to study pathogens that mosquitoes carry. (Forget the lions. Mosquitoes are the most dangerous African animals.) She carried some interesting equipment: a 3-D printed attachment that held test tubes and attached to a cordless drill, which she used to turn captured mosquitoes into a slurry, from which she could extract DNA and RNA—another process that used to happen solely in labs.

The extractions and reverse transcriptions worked, she said. Continued research on the data they pulled from the African mosquitoes will happen later this year.

Hepp also had an unexpected research accomplishment in Zambia. While explaining her research to one of the safari guides, he mentioned a local veterinarian who did surveillance for sleeping sickness, a disease carried by the tsetse fly. She met the veterinarian, who was Kalaluka Mbumwae, the lab director for the Kakumbi Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Research Station, where they do all the tests for the country.

“It was mind-blowing that this well-equipped molecular laboratory existed in a rural Zambian village and that I just stumbled upon it through normal conversation,” she said. “I asked the lab director if I could take a few samples back with me to see if I could sequence full Tryponasoma brucei genomes. He gave me five DNA extractions from infected cows and said, ‘Let us see what you can do.’”

With those extractions, she and her research group are working on protocols to sequence T. brucei genomes with the hope of understanding the circulation of the organism in rural Zambia, which will open up the possibility of collaboration with other researchers at NAU and in Zambia.

Making an impact on the community

The lions came up more than once on the trip’s highlight reel. So did the people they met.

“I don’t think I’m ever going to forget the people,” Henry said. “They were just amazing.”

The groups got to do community outreach while there. NAU offers the Maxwell-Lutz Community Impact Award, which provides funding to student teams doing an interdisciplinary project with a substantive community impact. Henry acted as the student leader, co-writing a proposal that highlighted the work they would do in Zambia and how it could improve the vitality of the local village, particularly for the schoolchildren.

With their $5,000 award, the team did three projects:

- Bought school supplies for the local school and made a book of traditional African children’s stories, which the schoolchildren illustrated. The book is for sale at the safari camp where they stayed, and the profits will fund scholarships for students.

- Took students from the village school into the park to explore and see wildlife. Most had never been to the park before, so the tour guides picked the students up in the jeeps and took them through the park, along with the NAU team.

- Purchased beekeeping suits for a local football (soccer in the U.S.) team that was putting up beehives around crops. For decades, elephants have fed off these crops, which the villagers use to feed and sustain themselves, leading to significant conflict between the two species and a worrisome number of elephant injuries and deaths. But elephants are afraid of bees, so the 6,000 hives around the fields would act as a deterrent, thus reducing elephant-human contact, as well as providing honey, another crop for villagers to sell.

The poverty they witnessed in Mfuwe also was a new experience for the NAU students. That made their contributions that much more meaningful.

“What sticks out the most is seeing the students. Our biggest goal was to help them out,” Tuengel said. “When we were in the United States, we felt like we didn’t really bring a lot of supplies, but when we were actually there and put it on the table in front of them, we realized this was a lot of stuff.”

“Often we go to these beautiful places and we’re taking—taking photos, taking this experience,” Walker said. “It was fantastic to actually be able to give back. That’s what this award let us do.”

The Maxwell-Lutz Award wasn’t the only money moving the project forward. Between flights to Africa, which are expensive, and staying in a tourist lodge, even with the steep discount they got, the trip was expensive. While students paid most of their own way, two friends of NAU donated funds to help offset costs. Retired forestry professor David Patton and alumna Judy Wheatley had slightly different reasons for donating, but both described a love for NAU and the experiences they want students to have.

Patton, who retired about a decade ago, actually went to Zambia in the 1960s, to the very park this group was going. When Carol Chambers told him about their upcoming trip, he and his wife, Doris, pulled out photos and journals from their year living and working in South Luangwa National Park, describing what the country, which at the time was brand-new, was like. In addition to donating money, his daughter, who went to school in Zambia and just retired as a teacher in Phoenix, donated school supplies from her classroom.

“Doris and I have three daughters, and we wanted them to work outside their environment,” Patton said. “My interest with this program was to help students do something that they’d like to do and otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to do it.”

Wheatley, a trustee for San Diego Zoo Global who graduated in 1970 with a degree in education, connected with Walker a few years ago through the owner of the Zikomo Safari Lodge, who collaborates with a wildlife conservation nonprofit called Nsefu. She started donating to Walker’s Bat Ecology and Conservation Lab, and when she learned about this program, she wanted to help.

“Faith shared her idea about the trip, and I saw it as a win-win, helping both my alma mater and Zikomo/Nsefu,” Wheatley said. “San Diego Zoo Global’s vision is to lead the fight to end extinction, so this was an opportunity to walk the talk.”

Heidi Toth | NAU Communications

(928) 523-8737 | heidi.toth@nau.edu