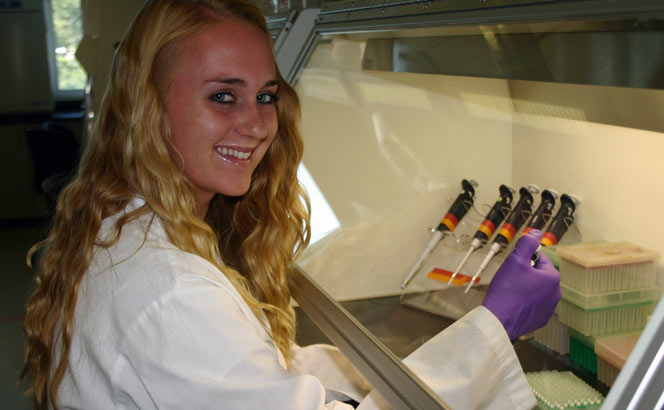

Meagan Seymour knew her career path before she finished high school in May 2009—laboratory-dwelling crime fighter specializing in forensics—and her tour of NAU’s Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics lab convinced her it was the right place to be.

She couldn’t have known when she enrolled at NAU that as a freshman she would help solve a mystery involving hundreds of cases of anthrax infections and the deaths of 14 people. It was an investigation that would involve law enforcement, health professionals and scientists from around the world and would backtrack the path of drug smugglers that led through Europe to the Balkan Route and south to poppy fields in Afghanistan.

The first two cases surfaced in December 2009. Unrelated heroin users with anthrax infections were admitted to a hospital in Glasgow, Scotland. Both died within days. Several cases surfaced in Glasgow, and eventually the net widened to England, Germany, France and Denmark.

News stories speculated on the source of the anthrax—was it terrorism, intentional tainting aimed at wiping out drug users or accidental contamination?

Paul Keim, Regents professor and director of NAU’s Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics, saw the news stories out of the United Kingdom and it grabbed his attention. NAU’s center has amassed the largest catalog of Bacillus anthracis in the world as a result of its role in tracking down the source of the 2001 anthrax letter attacks in the United States.

By January, Keim was on the case. The death toll had climbed to six with a total of 17 cases. Despite Glasgow officials releasing public service announcements and posting signs like the one at right warning of the dangers, drug users with anthrax infections kept showing up in emergency rooms.

“These are heroin users, it wasn’t like they weren’t already taking a big risk with their lives,” Keim said.

Thirty-four patient samples arrived at NAU in February. The lab work was assigned to several undergraduate students including Seymour. By that time, police had linked cases in London and Aachen, Germany.

Spenser Wolken, a junior majoring in biology, and Seymour began sequencing the entire genome of the samples, mapping millions of base pairs that made up its DNA.

The way to identify the source of an anthrax strain is similar to what is used with human DNA samples. Each anthrax strain has a string of DNA that can be mapped and compared to other samples. Just like human DNA, anthrax DNA has variations, and those are used for comparison with known strains.

Based on these practices, the students examined all 34 samples and found they matched each other. Next, they found the anthrax strain was in the same family to cataloged strains from Asia and Africa, and most closely related to two known strains from Turkey.

The investigative team in the U.K. was relieved to learn the bioweapons strain tested in the 1940s on Gruinard Island off of the coast of Scotland and the Ames strain used in the U.S. attacks in 2001 were eliminated as possible sources.

“One of the most powerful conclusions we can make in forensic analysis is to say what it’s not,” Keim said.

Based on the results, Keim told officials it was highly unlikely this was an act of terrorism.

Law enforcement officials supported the lab’s results based on that what they knew about drug trafficking in the U.K. Ninety percent of the heroin smuggled into England comes from the poppy fields in Afghanistan by way of the Balkan Route through Turkey.

The team concluded the most likely source of contamination came from farm soil where anthrax occurs naturally. Animals that die of an anthrax infection store the spores in their hides and bones. The heroin might have been cut with bone meal that contained anthrax spores or it may have been wrapped in a tainted animal skin. In fact, the police cited incidents in which heroin had been seized that was smuggled in goatskins.

Since that meeting in the spring of 2010, 200 cases and 14 deaths have been linked to the same strain of anthrax in heroin users. The Centers for Disease Control published the international team’s scientific findings associated with the investigation and an article ran in the U.K. edition of Wired magazine, detailing the multiagency effort to solve the case.

Wolken earned a bachelor’s in biology from NAU in May of 2010 and moved on to medical school. Seymour will graduate with a bachelor’s degree in biomedical science in December. She has continued her work in the center, testing some 500 samples and tracing many back to their geographic origins, results that contribute to the world’s catalog of known strains.

No cases were reported in 2011, but this year the contaminated heroin resurfaced. Since June, 10 new cases including two fatalities have been reported in the U.K., Germany, Denmark and France.