Global warming may initially make the grass greener, but not for long, according to new research conducted at Northern Arizona University.

The study, published this week in Nature Climate Change, shows that plants may thrive in the early stages of a warming environment but begin to deteriorate quickly.

“We were really surprised by the pattern, where the initial boost in growth just went away,” said Zhuoting Wu, NAU doctoral graduate in biology. “As the ecosystems adjust, the responses changed.”

Researchers subjected four grassland ecosystems to simulated climate change during the decade-long study. Plants grew more the first year in the global warming treatment, but this effect progressively diminished over the next nine years, and finally disappeared.

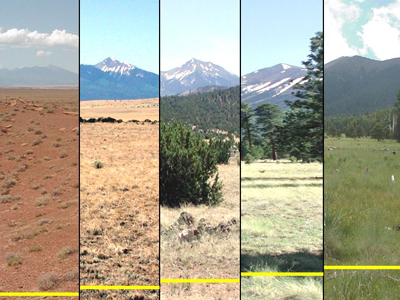

The research reports the long-term effects of global warming on plant growth, the plant species that make up the community, and the changes in how plants use or retain essential resources like nitrogen. The team transplanted four grassland ecosystems from higher to lower elevation to simulate a future warmer environment, and coupled the warming with the range of predicted changes in precipitation—more, the same, or less. The grasslands studied were typical of those found in northern Arizona along elevation gradients from the San Francisco Peaks down to the Great Basin Desert.

The researchers found that long-term warming resulted in loss of native species and encroachment of species typical of warmer environments, pushing the plant community toward less productive species. The warmed grasslands also cycled nitrogen more rapidly, an effect that should make more nitrogen available to plants, helping them grow more. But instead much of the nitrogen was converted to nitrogen gases lost to the atmosphere or leached out with rainfall washing through the soil.

Bruce Hungate, senior author of the study and NAU biological sciences professor, said the research findings challenge the expectation that warming will increase nitrogen availability and cause a sustained increase in plant productivity.

“Faster nitrogen turnover stimulated nitrogen losses, likely reducing the effect of warming on plant growth,” Hungate said. “More generally, changes in species, changes in element cycles—these really make a difference. It’s classic systems ecology: the initial responses elicit knock-on effects which here came back to bite the plants. These ecosystem feedbacks are critical. You just can’t figure this out with plants grown in a greenhouse.”

The findings caution against extrapolating from short-term experiments, or experiments in a greenhouse, where experimenters cannot measure the feedbacks from changes in the plant community and from nutrient cycles. The research will continue at least five more years with current funding from the National Science Foundation and, Hungate said, hopefully for another five years after that.

“The long-term perspective is key. We were surprised, and I’m guessing there are more surprises in store.”

Additional coauthors include George Koch, NAU professor of biological sciences, and Paul Dijkstra, assistant research professor of biological sciences. Wu completed the study as part of her doctoral thesis in biology and earned her degree in 2011.