By Kerry Bennett

Office of the Vice President for Research

Colonizing Mars as a backup planet for Earth has been a theme in both science fiction and popular science for decades, and NASA plans to send human explorers to the Red Planet within the next 20 years.

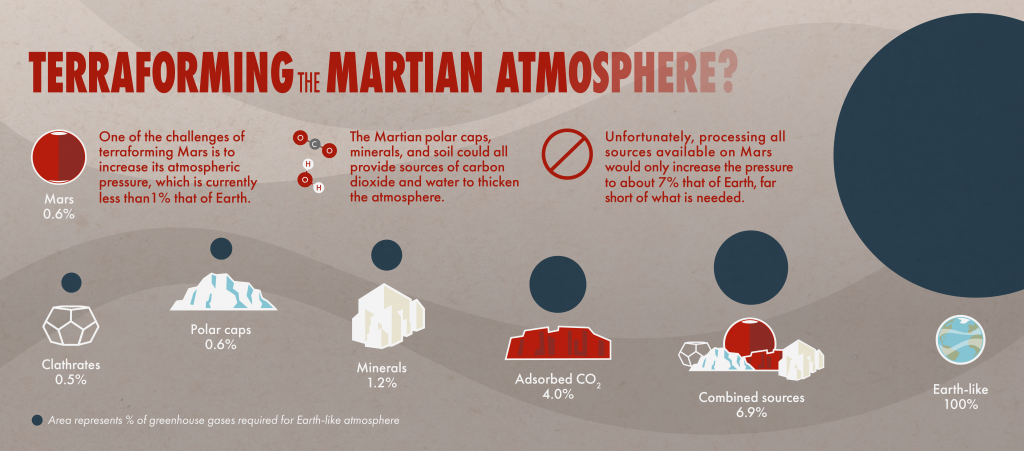

But how feasible is it for humans to explore or colonize Mars? With an average daily temperature at minus 67 degrees Fahrenheit, the inhospitable climate is too cold for humans, and the atmospheric pressure is less than 1 percent of Earth’s, requiring pressurized space suits and habitats for humans to live on the surface.

Proponents of “terraforming” Mars to make it habitable propose releasing greenhouse gases from the planet’s surface such as carbon dioxide (CO2) to trap heat, warm the climate and ultimately increase the atmospheric pressure. The plausibility of achieving this with current technology is the focus of a new study sponsored by NASA just published in Nature Astronomy.

The study, co-authored by Northern Arizona University planetary scientist Christopher Edwards, refutes the popular notion of terraforming by examining what would be needed to release carbon dioxide from several different sources. The paper serves as an inventory of CO2 available for terraforming Mars, including in the Martian polar ice caps, which would require vaporization on a massive scale; CO2 attached to the surface of dust in the Martian soil, which would require an enormous heating effort to release the gas; and carbon locked in mineral deposits, which would require extensive strip mining.

According to a NASA statement, the result takes advantage of about 20 years of additional data collected through spacecraft observations of Mars.

“These data have provided substantial new information on the history of easily vaporized, or volatile materials like CO2 and H2O on the planet, the abundance of volatiles locked up on and below the surface, and the loss of gas from the atmosphere to space,” Edwards said.

The study concludes that terraforming Mars—making the planet habitable enough for humans to explore and colonize without needing spacesuits and habitats—is not possible using current technology. And even if it were possible, releasing all of the gases still wouldn’t be enough to warm the planet.

“Our results suggest that there is not enough CO2 remaining on Mars to provide significant greenhouse warming were the gas to be put into the atmosphere; in addition, most of the CO2 gas that is there is not accessible and could not be readily mobilized. As a result, terraforming Mars is not possible using present-day technology,” said Bruce Jakosky of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, the study’s lead author.

Adding a dose of reality to the terraforming debate

“We conducted this study to add a dose of reality to the debate over terraforming Mars,” Edwards said. “As NASA prepares for future sample return missions and the human exploration of Mars that can further address key climate questions, these findings on the inventory of volatiles continue to lay the groundwork for our understanding of the Martian climate—past, present and now future.”

An assistant professor in NAU’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, Edwards was recently awarded a $1.2 million grant from NASA to understand the habitability of Mars by studying extreme, Mars-like environments on Earth. As principal investigator, Edwards will lead a team of NAU graduate students and scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey Astrogeology Science Center, Stony Brook University, the University of New Mexico and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to study several field sites in California’s Mojave Desert, one of the hottest, driest places on the continent.