By Kerry Bennett

Office of the Vice President for Research

A new paper published in PLOS Pathogens by a team of researchers comprised of Bruce Hungate and Ben Koch from Northern Arizona University; Lance Price from George Washington University and the Translational Genomics Research Institute; and Gregg Davis and Cindy Liu from George Washington University outlines the critical need for further research into the nature of colonizing opportunistic pathogens, or COPs.

Since the National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched the Human Microbiome Project in 2007, scientists have been studying the symbiotic relationship between the human body and the trillions of organisms that inhabit it. Among their discoveries: opportunistic pathogens, which take advantage of weakened immune systems, are prevalent in healthy individuals. These pathogens—bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses—colonize the human body and, when conditions are right, can cause a wide range of serious infectious diseases.

Bacterial COPs are of particular relevance because of their major contribution to today’s antibiotic resistance crisis and include a long list of notorious bacteria that have double lives as passive stowaways and virulent foes. These pathogens, or “beasts,” can cause insidious epidemics, because no symptoms are present when they colonize the body; the period between colonization and infection is unpredictable; and new clones transmit widely—even globally—among healthy populations before being recognized. For example, by the time the extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) strain ST131 was discovered in 2008, it had spread to at least three continents. To date, this drug-resistant superbug has caused millions of urinary tract infections and thousands of deaths.

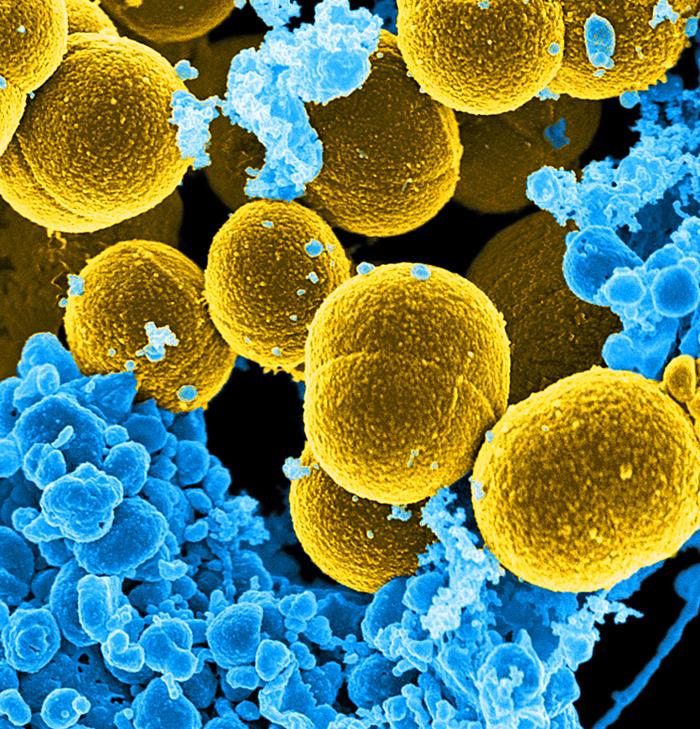

One of the best-known COPs is Staphylococcus aureus, which colonizes the nasal cavity and skin and causes cellulitis, abscesses, osteomyelitis, endocarditis and sepsis—as well as the methicillin-resistant variety (MRSA) that is a worldwide problem in clinical medicine. Another type of COP is Klebsiella pneumonia, a superbug that colonizes the oral cavity, skin and intestinal tract, causing a range of diseases, including cystitis, pneumonia and sepsis. And Streptococcus pneumonia colonizes the nasopharynx, causing otitis media, pneumonia and sepsis.

The researchers call for a new research framework to characterize the ecology of COPs, which they believe is paramount to understanding COP epidemiology and for new active and integrative surveillance programs of COPs.

“Much research will have to be conducted on the species or strain level,” the authors conclude, emphasizing that “characterizing the full scope of COP ecology—from persistence in environmental reservoirs to transmission among humans—is key for taming these beasts in all of us.”