For Tommy Rock, science is personal. Every question, every test, every positive sample of toxicity represents the face of a person from the Navajo Nation who has struggled with illness. His grandfather, who died in 2006. A friend fighting cancer for the second time. A relative whose funeral he attended just a week ago.

Rock, a doctoral student in earth science and environmental sustainability at Northern Arizona University, grew up in Monument Valley, a member of the Navajo Nation. Since he started his master’s degree in 2006, his work has focused on his people and the adverse effects they’ve experienced from abandoned uranium mines throughout the reservation. According to the National Institutes of Health, exposure to uranium can lead to cancer and kidney problems.

Now, in addition to his research, he’s working on raising awareness, with two speaking engagements planned for next month and a number of people who have reached out to him with questions.

“For me, everything I’m doing is personal,” he said. “I’m passionate about what I do. It’ll help not only my family and friends, but others as well.”

A decade of varying research

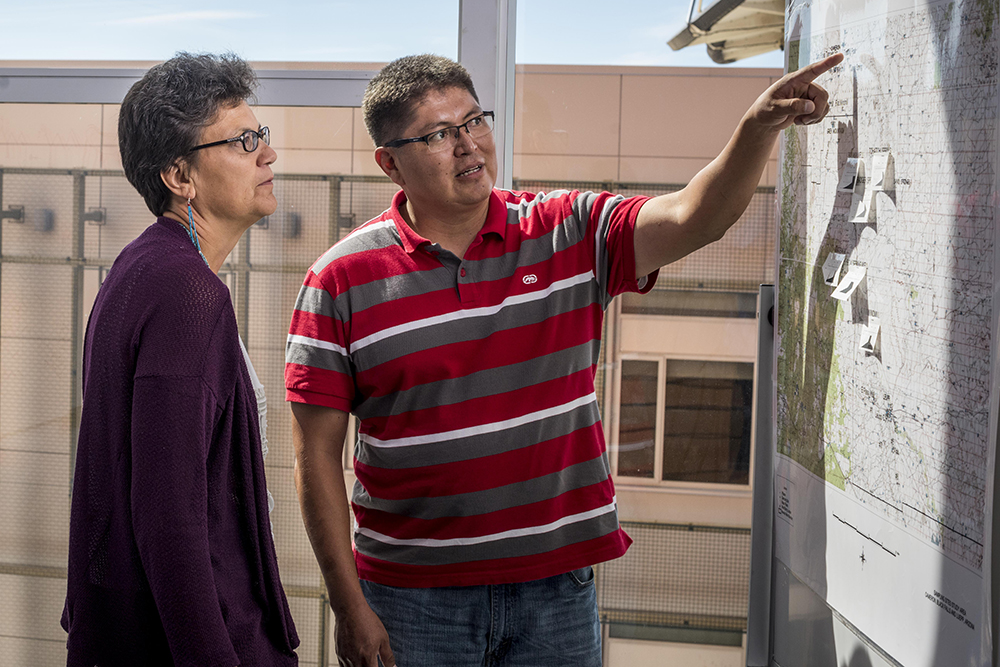

When he started his master’s degree, Rock worked with Jani Ingram, an associate professor of analytical and environmental chemistry. He did geographic mapping, highlighting wells, uranium mines and cities, tracking the water supply to the Navajo Nation.

After earning his master’s degree, Rock worked as a researcher for the University of New Mexico, then worked with the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2012 he returned to NAU for his doctorate, earning funding from the Center for American Indian Resiliency and the Native American Cancer Project for his research.

His research for his dissertation focuses on toxicity in sheep. A method originally crafted by the Suquamish, a tribe in the Pacific Northwest, was used to determine how much petroleum byproducts contaminated shellfish. Ingram and Rock then created a methodology to test the levels of uranium contamination in sheep.

The first step, which they completed recently, tested how much toxicity was actually in sheep in the region and what tissues it was concentrated in. The next step, for which he is getting approval from the necessary entities, will allow Rock to work with residents in Cameron to understand how they consume sheep: how much, what parts, how frequently they eat sheep, how it’s cooked, etc. This will provide an idea of how much of the contaminants people are ingesting when they eat sheep.

His dissertation will include a list of policy recommendations for the Navajo Nation and other entities. Possible policy changes might include a label about contamination such as that found on fish high in mercury or warnings about how to cook sheep to reduce exposure to contaminants.

“Tommy has done tremendous work on issues of great importance to the Navajo Nation,” said Ingram, Rock’s research adviser. “Overall, Tommy is one of the most persistent and compassionate students I have worked with. He is very well-respected by both Navajo community members and environmental health researchers working on tribal lands. I look forward to seeing the impact Tommy will have on environmental health in the future.”

Rock is working with Dine College and UNM on this project, which is funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. It builds on work he did previously in Sanders, also in the Navajo Nation, which found high levels of uranium contamination in the city’s water supply, leading to poorer health outcomes. The revelation garnered national attention and led to a change in how water is treated and residents are informed about what’s in their water.

That research led to an invitation to Chicago and Madison, Wisconsin, to give a talk titled “The Navajo Water and Rock Talk,” as well as become a contact for students throughout the nation who are doing research or becoming activists.

“This topic of environmental justice—a lot of tribes can relate to that,” Rock said.

What’s next

He’s big on empowering people. While he was working in Sanders, he and one other scientist were the only experts around most of the time. They taught the residents, answered questions and helped them become experts about their issues, encouraging them to call him whenever they needed to. And they did.

“I was really happy they called me,” rock said. “They’re taking the initiative to learn more, for me to teach them some basic concepts and for them to run with it. It shifts the power into their favor so they understand what’s going on. It empowered the community, and I want to do more of that in this way.

“So far we have one victory, which is pretty cool,” he said.