By Heidi Toth

NAU Communications

Robyn Martin was a non-traditional undergraduate student at Northern Arizona University just trying to finish her degree when two of her English professors suggested she go to graduate school. She’d never considered it before.

Today, she has a doctorate and is a senior lecturer in NAU’s Honors College, taking students on field trips through rivers and canyons to teach them about life.

Frederick Gooding Jr. entered college with no idea being a professor was even a career choice for him. He had never seen a black professor before he enrolled at Morehouse College.

Today, he is a professor of ethnic studies at NAU who is the adviser for the Black Student Union and six years ago started Hip-Hop Appreciation Week, an annual event that allows his students to take center stage and teach.

Keola Wong was a struggling undergraduate student who just scraped by in his critical first year of college. He was a first-generation college student with little help, financial or otherwise, from his family and he struggled to ask for help, not doing so until working on his graduate degree at NAU.

Today, he is the adviser for the HAPA Hawaiian Club and a program coordinator for Student Support Services at NAU whose office is a safe place for struggling students to come vent, ask questions and get help.

Precilla Cox, a first-generation student, experienced culture shock when she came to Flagstaff from Hawaii. But she powered through her undergraduate career before finding herself stuck in a job she didn’t want to keep doing but had no long-term direction and a baby on the way.

Today, she is an academic adviser whose job description allows her to help students find their place on campus, get comfortable in their classes, direct them to resources and be their cheerleader when needed.

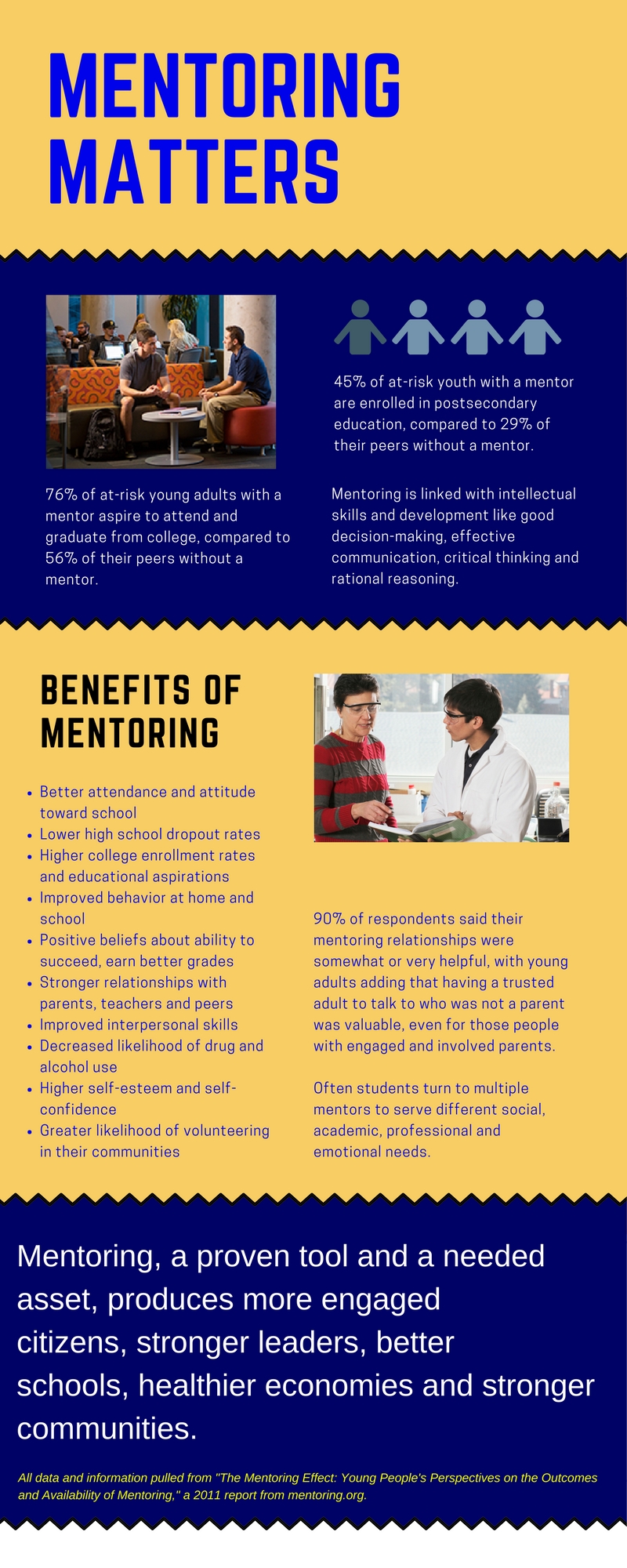

Each shared one critical factor to success: a mentor, or multiple mentors who suggested career paths, provided connections to job and scholarship opportunities, offered encouragement, support and resources and emphasized to these scholars that they weren’t taking on these challenges alone.

And all now have made being a mentor to students part of their careers, showing the same faith their mentors once showed (and in many cases continue to show) in them.

“I want them to have an understanding that I’ve been where they are and have something to share with them,” Gooding said. “Hopefully I can share a thought or two that can last with them.”

Finding a mentor

NAU has many formal mentoring programs and mentoring requirements, including Peer Jacks, undergraduate research and the Honors College. All contribute to students’ success.

Informal mentoring is outside of these relationships. It starts as Cox’s did, with her membership in the HAPA Hawaiian Club as an undergraduate; advisers Amy Websdale and Emilly Borthwick-Wong helped her with the transition from Hawaiian culture, which is community- and family-centric, to a more individualized focus as a college student without much family support.

“I came to college not knowing what I was doing,” Cox said. “My mom threw me in here and said, ‘If you want to go to college, you’ve got to figure it out.’ As far as navigating everything here, I pretty much did it on my own.”

Leadership positions in the club led her to build better relationships with Websdale, who was her first adviser, then Borthwick-Wong, another native Hawaiian who at the time worked in Student Services. Having two women who understood both the culture she came from and the culture she was in, helped Cox through those difficult early times.

“I feel like if I didn’t have someone there, I would easily have gone back home to Hawaii,” Cox said. “We see that a lot with our students who come from Hawaii. A lot end up going back home. They might not have that role model, and things just aren’t working out for them here.”

The data show that’s not atypical. While mentoring is useful to all young adults, it is particularly beneficial for students from minority households or first-generation college students.

In a study from MENTOR, 99 percent of young adults in informal mentoring relationships reported the experience helped them find support in personal development, with mentors offering advice on school and career but also family and personal situations.

That is the type of relationship Gooding developed with Aeryana Earl, an NAU sprinter who graduated in May with a degree in business management. Although she had support from coaches, trainers and academic advisers, she met Gooding when she took one of his classes and joined the Black Student Union. When Earl applied for the Gold Axe award, she listed Gooding as the NAU employee who most influenced her—one of two winners to do so.

“He’s just someone that I can talk to, that I know I can go talk to—about school, financials, anything,” Earl said. “He was easy to talk to because he was more than just an adviser to me.”

Many students find their mentors in the classroom. That was the case for Martin, Gooding and English professor Monica Brown, all of whom went to grad school and eventually became professors themselves on the advice of trusted professors. All of them found mentors among professors who were like them.

For Martin, it was about finding peers her age.

“Most of my fellow classmates were quite a bit younger than I was, so I sought out mentors in my professors,” she said. “Most of them were closer to me in age, and it was easy for me to make connections and relate to them much more as colleagues and less as authority figures.”

Gooding and Brown found professors who shared their race. Brown was taking a Chicano literature class her senior year at University of California-Santa Barbara when the professor, Carl Gutierrez-Jones, invited her to his office.

“He said, ‘Monica, have you ever thought about grad school?’ And I had not,” Brown said. “It took this one professor to put that idea into my head, and it really made a huge difference; I literally wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing. It’s kind of crazy—one conversation in one office hour with one Latino professor.”

While at Morehouse, a historically black university, Gooding had two professors, Marcellus C. Barksdale and Melvin B. Rahming, approach him. They thought he would be a good fit for a scholarship program for students who wanted to attend graduate school. Until that conversation, Gooding said, he’d never thought about going to grad school.

“It was the first time that I actually was in the presence of black scholarship,” Gooding said. “I didn’t even know what a Ph.D. was.”

He didn’t go to grad school right away, but eventually got back to the classroom, first as a doctoral student and then as a professor. And it started that first day of school and continued when black professors took an interest in him.

“The idea is that the seed was still there,” he said. “That never would have happened had I not seen someone who reflected my essence.”

Ecology professor Jane Marks found her mentors, and now finds mentees, through research. During her graduate coursework, she signed up for a biology class. The professor saw her potential and offered her the opportunity to do a master’s program in his lab. The problem? She had an English degree and didn’t meet the requirements for admission. He admitted her anyway.

She found more mentors as a doctoral student in Berkeley, and since coming to NAU as a professor in the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (Ecoss) has made a point of ensuring students, particularly undergrads, have opportunities for research and academic and personal development as well as support. The Ecoss professors have fostered a climate of belonging among their students, she said.

“I think it’s equally important to give them a home,” she said. “We have a lot of students on work study, and it gives them a place to be between their classes. It’s where they keep their backpacks, it’s where they leave their books. They’re learning, but they’re also finding a home and a place to be during the day where people are working versus less productive places. I think it helps them stay on track.”

Short- and long-term benefits of mentoring

Wong didn’t have a mentor until he started his master’s degree in elementary education at NAU. Through his graduate assistantship, he met Melissa Welker, executive director of the Student Success Programs and Initiatives, and she became his mentor.

“This is where I realized what I wanted to do: help students graduate from college,” he said. “As a first-generation, low-income college student I struggled through college never seeking help. I wanted to be there to help guide, mentor and challenge students to graduation.”

Cox also mentors students as part of her work as an academic adviser. Most of the students who need her help have a question or two or need guidance now and then; she doesn’t build much of a relationship with them. Some, though, she does. Last year a couple students came in weekly with question and concerns. Both were first-generation students, she said, and were having similar experiences to hers during those first months at NAU.

Cox herself still has mentors. She turned to Borthwick-Wong after graduation, when she learned she was pregnant and realized she needed a more stable job than waiting tables. But she wasn’t sure if she wanted to stay here or to return to Hawaii to work in the hospitality industry.

She talked it over with Borthwick-Wong, who had an open temporary job in the advising office. Cox applied.

She didn’t get it.

“She and I really then started working on her interviewing skills and being able to pull from different life experiences,” Borthwick-Wong said. “I think students, when they’re looking at careers, they stick with what they’ve done as a job, and not the life experience they have.”

Cox got the next open job and has since been promoted. She is working on her master’s degree with encouragement from Borthwick-Wong. It’s hard, she acknowledged, especially with two children at home.

Photo credit: Sydney Hickey, NAU Communications

“Emilly was just always pushing me to do better and find better,” Cox said. “To be better.”

Having people “on the inside,” be it with jobs or internships, research or networking also can help as students progress in their careers. At Ecoss, Marks takes students to the annual Society for Freshwater Sciences conference. They often give papers or presentations, and the society has so many undergraduate students coming now that its members created a student track, allowing them to network with the peers as well as the scientists whose work they study in class.

“It’s a real a-ha moment for students in terms of who these people are that publish in scientific literature,” Marks said. “It’s a real transition from understanding a course pack to, ‘Oh, this is how science works. It makes science more accessible.”

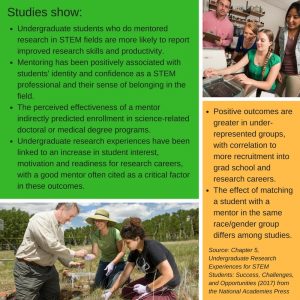

She observed that NAU as a whole has made undergraduate research a top priority, which promotes the type of mentoring experiences positively correlated with students finishing college, staying in STEM fields and feeling confident about their abilities as researchers. The correlation is especially strong for students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, according to a 2017 report from the National Academies Press.

Marks saw that up close a few years when a struggling student started in her lab. He was in danger of failing out of school through his first year, and his second didn’t start off much better. Working in her lab was the best thing going on his life, she said.

Then he became friends with her graduate students. His partner worked in Marks’ lab as well—“I don’t know if they fell in love in my lab or not, but one way or another they ended up working together”—and by the time he graduated, her struggling student was a scientist with research presentations to his name.

“It gave him a place to grow up and to get serious and to build his grade point average, then ultimately get a master’s degree,” she said.

Finding and building a relationship of trust

Students share the responsibility for these relationships with professors, supervisors and advisers.

Martin said she works hard to get to know her students in class, including learning their names and emphasizing her availability during office hours. This helps her become an authority figure students trust.

“I’ve had students ask to meet me for coffee because they weren’t sure they wanted to jump right into graduate school post-baccalaureate career, and they wanted to simply have someone to talk to who could listen informally and perhaps help them figure out pros and cons of both choices,” she said.

She also routinely teaches experiential education courses, where the classroom is often the great outdoors.

“That type of atmosphere has allowed my students to open more intimate types of dialogue with me as

we float down a river in a kayak or talk around a campfire at night that a formal brick-and-mortar classroom atmosphere might not,” she said.

Gooding has found study abroad trips and advising to be more conducive to building relationships than just interacting in the classroom, though he also makes an effort to be approachable in the classroom. He doesn’t just lecture and leave, he said; he comes a little early, stays a little late and while he’s teaching he brings enthusiasm for the subject into the classroom, hoping to inspire conversation among his students.

In research, the mentoring relationship can grow naturally. Ecologist Jeff Muehlbauer, who recently returned to Flagstaff to work for the U.S. Geological Survey, worked in Marks’ lab for his four years of undergraduate studies. Marks and her graduate student walked him through the processes of ecological research.

“I never really got a whole lot of mentorship from them in the sense of life goals, but they were very helpful in teaching me how to be an ecologist,” he said. “I really see that opportunity as having been critical to my career.”

Both women also wrote him letters of recommendation for graduate school at the University of North Carolina, where he earned master’s and doctoral degrees. That is critical, Marks said, especially for students who want to go to graduate school.

“I remind my lower division students: You need to have two to three people who can write you a letter of recommendation who actually know you,” she said. “You really want to find some experiences that are external to the classroom.”

However the relationship begins, building it needs to be a concerted effort on both sides, Wong said. He wants students to know they can talk with him and ask advice about anything. He also wants to make sure they can handle getting important feedback that’s not always easy to hear.

“It’s important to build a trusting relationship with my mentee,” he said. “If trust is not built, then it will be hard for my mentee to hear the good and the bad stuff.”

Nor does the relationship end when students move their tassels from right to left on graduation day. Muehlbauer attends weekly reading sessions with Marks and her students. Cox still bounces ideas off of Borthwick-Wong, who still seeks advice from Welker. Earl still has Gooding’s number programmed into her cell phone and will call or text for advice.

“College was definitely a challenge for me on a personal level, being away from home and in a new environment,” Earl said. “Having other people to talk to, older people who probably went through the same things I went through or have seen other students go through it, having their input made it worthwhile.

“I could walk into someone’s office and talk to them for a while, and after that I’d feel better. They definitely made my college experience better.”