Results from Northern Arizona University’s Vulcan Project estimating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuel combustion for the entire U.S. show close agreement to a new atmospheric-based approach for estimating these same emissions, as reported in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The alternative approach, devised by researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the University of Colorado Boulder, uses ambient air samples and a well-known isotope of carbon (“14C”) that scientists have relied on for decades to date archaeological sites. NAU’s Vulcan Project, by contrast, uses a multitude of data such as local pollution reporting, fuel statistics and traffic activity. Vulcan was unique among the many estimates compared to the new atmospheric-based approach in that matched the atmosphere to within 1.5 percent on an annual basis.

“The degree of agreement from these completely independent approaches is astonishing,” said Kevin Gurney, a professor in NAU’s School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems, co-author of the publication and Vulcan Project lead scientist.

Accurately calculating emissions of carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels has challenged scientists for years. The two primary methods in current use—”bottom-up” inventories, such as the Vulcan Project, and “top-down” atmospheric studies used in regional campaigns—each has strengths and weaknesses. Bottom-up inventories can provide more detail than top-down methods, but their accuracy depends on the ability to track all emission processes and their intensities at all times, which is an intrinsically difficult task with uncertainties that are not readily quantified. Top-down studies are limited by the density of atmospheric measurements and our knowledge of atmospheric circulation patterns but implicitly account for all possible sectors of the economy that emit CO2.

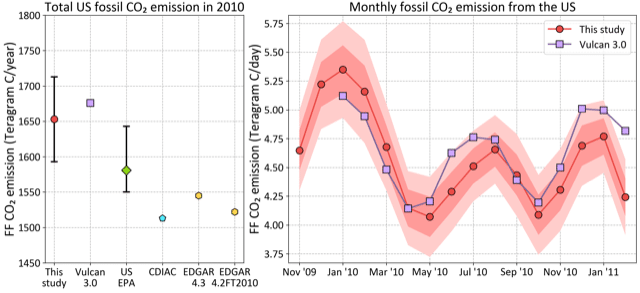

The team constructed annual and monthly top-down fossil CO2 emission estimates for the U.S. for 2010, the first year with sufficient atmospheric samples to provide robust results. They compared their atmospheric-based result to a number of bottom-up estimates, including the Vulcan Project and the recent U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) report of 2010 emissions. The Vulcan Project estimate was within 1.4 percent of the atmospheric-based approach while the other bottom-up estimates showed differences ranging from 4.5 percent to almost 9 percent, all lower than either Vulcan or the atmospheric-based results.

“Not only have our atmospheric colleagues made an important advance in using novel atmospheric measurements to estimate greenhouse gas emissions, but the integration of Vulcan and the atmospheric-based approach hold the promise of a new greenhouse gas emissions information system that can conclusively and independently assess the nation’s climate impact using state-of-the-art science,” Gurney said.

With an expanded 14C measurement network combined with the high-resolution Vulcan Project

estimates, states such as California and cities throughout the U.S. that have pledged aggressive emission reductions can use these new scientific approaches to prioritize the emission reductions, track their progress and assess outcomes.

“Independent verification of annual and regional totals and multi-year trends using independent methods like this would promote confidence in the accuracy of emissions reporting, and could help guide future emissions mitigation strategies,” NOAA scientist John Miller said.

As these were the first estimates constructed using the new observing system, scientists cautioned that they should be considered provisional. Now they are busy applying the method to measurements from subsequent years to determine if the differences are robust over time.

“This work takes a dramatic step toward a greenhouse gas information system that can fundamentally change the way cities, states and the nation tackle the climate change problem,” Gurney said. “Not only can we guide reduction to the most important sources at all scales, but we can confidently assure the public and governments that the intended reductions did occur.”

The study was supported by NOAA, NASA and the Department of Energy. Other members of the research team included scientists from the University of California at Irvine.

Kerry Bennett | Office of the Vice President for Research