The work is a labor of laboratory technicians poring over the genetic details of a bacterium, with researchers searching globally for links and associations that might help explain—and perhaps someday prevent—an illness in Flagstaff.

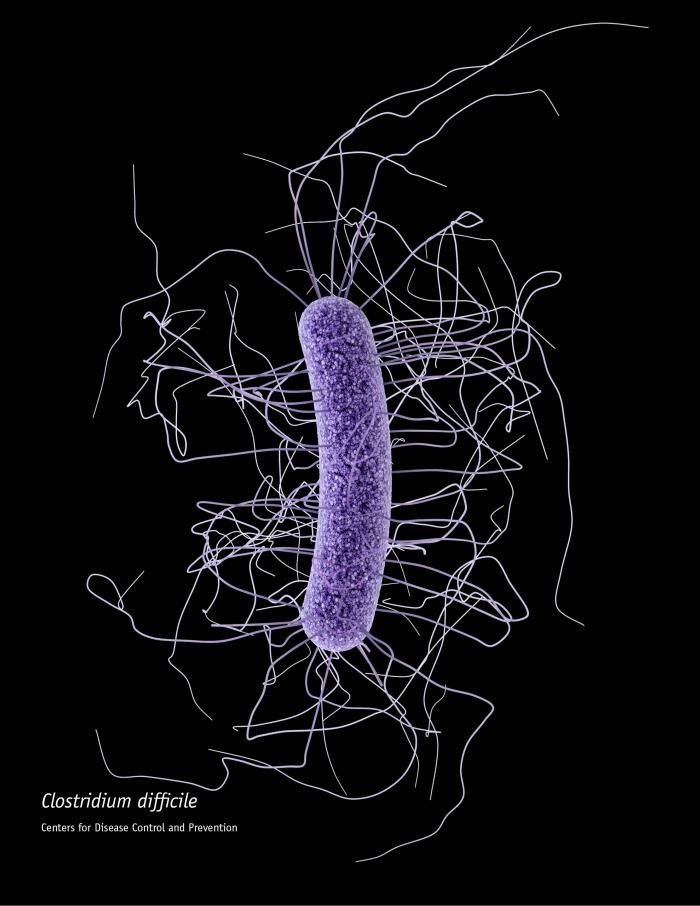

From the dark, hidden world of Clostridium difficile, or C. diff, to the wider world of daily life, Northern Arizona University researchers are beginning to discern pathways tracing from organism to outbreak. A $200,000 grant award from the prestigious Flinn Foundation has opened the newest line of inquiry.

“C. difficile is a huge problem in the healthcare setting,” said Jason Sahl, assistant professor of biological sciences at NAU’s Center for Microbial Genetics and Genomics. He said there’s a multi-billion dollar financial burden associated with treatment of C. difficile colitis, which is the most common hospital acquired infection in the United States.

Sahl explained that an imbalance of C. diff in the human gut microbiome, often resulting from intensive antibiotic use, can induce the expression of toxins that cause severe diarrhea resulting in thousands of deaths. But he said this project is not aimed directly at treatment.

“What we’re interested in is where the C. diff is coming from and how it’s circulating between the hospital and the community” Sahl said. “By understanding that information, we can come up with interventions or treatments to stop the spread at the beginning so it never becomes a problem that has to be treated.”

With the latest infusion of funding, technicians are performing whole genome sequencing on C. diff found in stool samples that come from a clinical setting. Sahl and his colleagues can then compare the genetic signature with samples from other local sources, such as meat products and dog fecal samples, to find similarities.

What they are beginning to suspect is that despite C. diff’s reputation as a hospital-acquired infection, people are being infected from other sources in the community. Sahl said he’s already seen a diverse collection of C. diff locally, which points to a community reservoir.

“If we could somehow go in and link some of these sources together, we can start to see some of these transmission networks,” Sahl said. “We could develop an understanding of how people are getting sick with C. diff before they even go to the hospital.”

For example, Sahl noted that 17 percent of dog fecal samples collected from throughout Flagstaff have tested positive for C. diff.

“We’ve already found a couple of types of C. diff in Flagstaff from both dog fecal samples and human clinical samples,” Sahl said. “We can’t say that one was directly used to infect the other but it does tell us there are certain types of C. diff that easily infect dogs as well as humans.”

While Sahl said Flagstaff’s relative isolation makes it an ideal area for this type of research, it is also the availability of global data that makes his job a little easier.

“Researchers worldwide are also sequencing C. diff and putting their findings into public databases,” Sahl said. “We can download their sequences, compare them to what we sequence here in Flagstaff, and start to see global transmission networks. So we can ask if we’re seeing a type of C. diff that’s found only in Flagstaff, or if there are types that pop up worldwide. That’s where the power of these databases really comes in.”