By Heidi Toth

NAU Communications

A partnership between Northern Arizona University and a Flagstaff community organization has led to hands-on research opportunities for students and a wealth of information and training materials for local educators and community groups.

A pod in NAU’s Community and Public Inquiry (CUPI) program spent this year collaborating with the Northern Arizona Interfaith Council (NAIC), researching the challenges immigrant families in Flagstaff face in the public school district and offering recommendations to resolve some of those concerns. The group then created a training program to help teachers and administrators in the Flagstaff Unified School District better connect with this population.

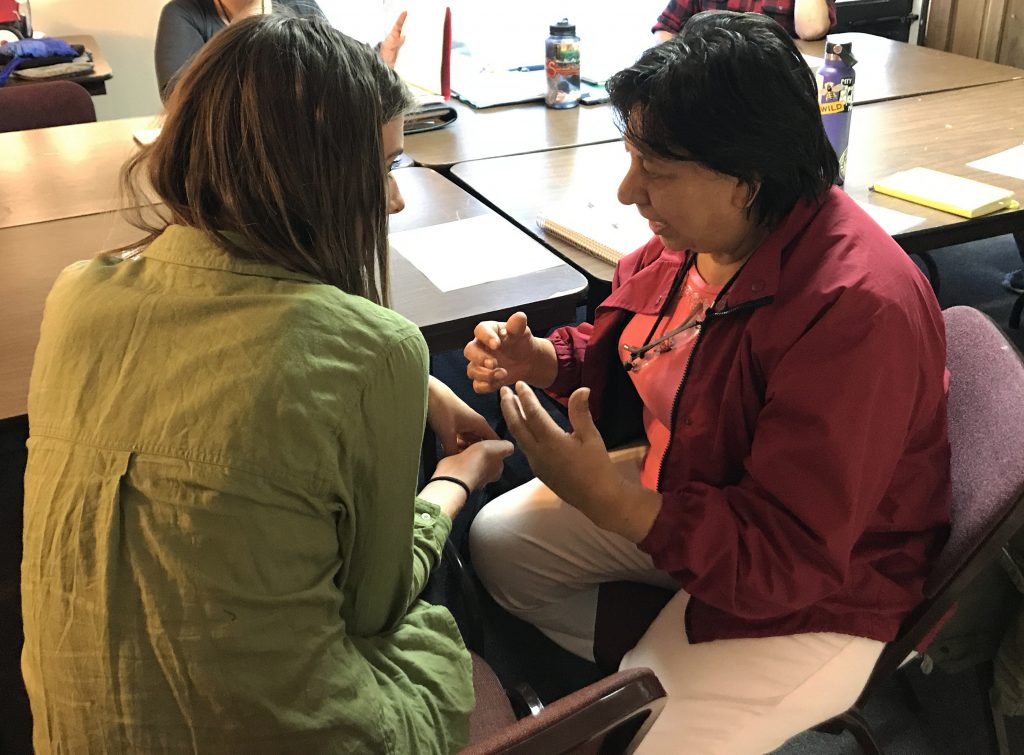

The project, led by anthropology lecturer Leah Mundell, who also is the faculty adviser for NAIC, connected NAU researchers and students with community organizations to develop research to expand organizations’ capacity and also offered students the opportunity to participate in research about which they were excited. Undergraduate students Aaron Arrellano-Haring, a senior anthropology major; Paula Moroyoqui, a senior biomedical sciences major, Vanessa Savel, a junior Spanish major, and graduate assistants Jorge Garza and Danielle Austin, both earning master’s degrees in Sustainable Communities, held meetings, conducted interviews and worked with various community leaders to examine the needs of immigrant populations within the Flagstaff community—information NAIC and FUSD didn’t have the resources to gather on their own.

“It’s been amazing value added for the NAIC because of all this energy and time that students can bring,” Mundell said. “So often we say, wouldn’t it be great if we could do these things? Now maybe we can.”

What is CUPI?

The Community and University Public Inquiry program, which is part of Sustainable Communities, started about two years ago. Criminology and criminal justice professor Luis Fernandez, who also is part of Sustainable Communities, saw the University College offered civic engagement programs to first-year students. They were popular, but with constant turnover it meant projects essentially started over each semester.

Fernandez decided to create a similar program, but working with older students. They would still work with community organizations, but the final step in their semester-long project was to present next steps that the next group would take on. The first semester, 10 undergrads and a grad student worked with the Grand Canyon Land Trust. From there, it’s grown to five pods, all working with a different organization, including the Jabulani School Simulation, Flagstaff Foodlink, NAIC and the Black Mesa Water Coalition, which has since ended.

Next semester, there will be even more pods—some science-based, some art-based, all interdisciplinary and working on an inquiry-based issue through the manner they’ve determined will best solve it. CUPI doesn’t tell groups how to solve the problem, Fernandez said. Part of the inquiry process is to identify processes in the course of coming up with answers.

“We’re capitalizing on the ability of humans to come together and ask a series of questions and try to figure out answers to those questions,” he said. “It can be done in all sorts of ways. CUPI is all about teaching the students how to ask good questions and find good answers.”

In the short time CUPI has been going, Fernandez has seen benefits at all levels. Community organizations have additional resources to address problems. Undergraduate students are getting research experience and job skills. Graduate students are getting experience managing a project and pod and collaborating with others. They’re all learning that failure is an acceptable part of the inquiry process.

This has contributed to the program’s growth. Fernandez said other departments have taken notice about the benefits such hands-on, engaged research has for their students. In addition to the initial funding from the provost’s office, the Honors College, the School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability and the Center for International Education have all provided funding as well.

“We want the students to aim at transformation,” Fernandez said. “The key here is to figure out how to do good things in the world and transform the world into a better place, and we want that to be done through inquiry, not just through action. We want to show that actually asking questions is a very powerful thing to do.”

Bringing people together

The NAU research team’s goal was to identify obstacles for incorporating immigrant families into the Flagstaff community through better and more effective access to quality education and suggest ways to overcome those obstacles. NAIC had already been trying to establish closer relationships with FUSD, mostly around better serving immigrant families in terms of access to higher education, and Mundell saw how NAU students could help in this mission while collecting data for a research project.

When they started three semesters ago, Garza said their first task was interviewing people—school counselors, immigrant leaders, educators, families, students. They asked what immigrant families needed from public education, from higher education and from other resources in the community and what their priorities and concerns were.

“We really just wanted to find out what was most important for them,” Garza said.

They found families needed unique support from educators and schools. This ranged from emotional support in the classroom and teachers having an understanding of the challenges to having more resources available, such as documents in Spanish and translators at meetings, to providing resources to help students fill out paperwork to apply for jobs, scholarships and college.

Armed with that research, the team designed a curriculum for educator training, which they started this year with FUSD. Using a grant from the Arizona Community Foundation of Flagstaff, 60 teachers attended voluntary two-hour professional development trainings. Additionally, they had a one-hour training meeting for FUSD’s administrators, including principal and a good percentage of the administrative staff.

The trainings were eye-opening for the trainees and the trainers. Most students don’t bring up their immigration status, the status of other family members or the unique challenges they face. Teachers may not be aware of what their students face outside of the classroom, so they don’t know how to help them as a group or as individuals.

Garza recalled a teacher who had been in the classroom for a decade who told them she didn’t know of any undocumented students in her years of teaching. She didn’t know undocumented students could even register for school.

“She probably had several dozen throughout that decade, who she didn’t even realize needed extra support,” he said.

Another focus is giving educators the language they need to communicate with families. Sometimes that literally means the language being spoken; parents who only speak Spanish or speak only a little English are less likely to go to parent-teacher conferences or other meetings at the school or are less able to effectively advocate for their child. Having Spanish speakers available to translate at meetings and sending home announcements in Spanish allows parents to be more involved in their child’s education.

“Schools and educators providing language access plays a vital role in being inclusive of the immigrant population,” Savel said. “Parents want to be involved in the education of their children, but if they cannot understand English, they are deprived of their ability to do so.”

Other times, it’s not the language being spoken that makes a difference but how parents and teachers communicate. NAIC wants to educate teachers on the changing policies related to immigration and how they can help students navigate a system that is frequently in flux. Teachers don’t need to have all the answers, but simply knowing the situation the family is facing can make a difference.

“So far, a lot of the families have not seen the school as a resource,” Mundell said. “That’s what we’re trying to turn around.”

Next steps

The group will schedule more trainings, and they also want to follow up with the teachers and administrator who have already gone through a set of trainings. Mundell said they want to establish teams in each school that will help the schools move forward in serving all of their students better.

“We’re hoping that will be broadly representative, so a teacher, a counselor, a parent and an administrator,” Mundell said. “We want it to be people who are committed. Those will be the ones who keep up on policy and resources as things change, so staff and parents have someone to come to, and look at what needs to be changed in the school.”

They’re collecting surveys from participants to gauge how effective the training is and continuing to present opportunities for dialogue, and the students presented their research at the Undergraduate Symposium in April.

They also are looking for more NAU students to get involved. Moroyoqui and Arellano-Haring graduated in May, and Savel only has one more semester. Those interested in participating can contact Mundell.