Bridget Barker remembers the day a doctor found a weird nodule in one of her lungs.

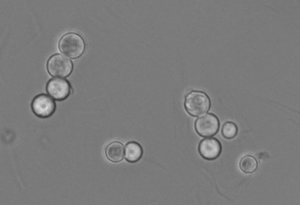

The Northern Arizona University biology professor felt a moment of panic—lung cancer!—before her brain asserted the likelier possibility. At some point the biology professor had been exposed to Valley fever, a fungal infection common in the hot, dry regions of Arizona, and her body had fought off the infection without making her sick. The nodule was a self-contained bundle of fungal spores and the dead white blood cells her body had sent to attack it. It was likely harmless—likely being the operative word.

Even Barker, who has studied Valley fever since 2002, doesn’t know the future of that nodule in her lung. It’s possible it could lie dormant for the rest of her life with no more effects than when it popped up the first time. It’s also possible at some point it could be triggered, releasing the fungal spores back into her body. The disease is so understudied scientists just don’t know what happens with long-term infections.

“Fungal diseases are really off the radar,” Barker said. “There’s not a lot of people working on it, so there’s a lot we don’t know.”

Barker started with Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute in August after years of studying Coccidioidomycosis (Cocci for short) and Valley fever in her doctoral program at the University of Arizona and more recently in the private sector. In that time she’s learned much about the fungus and the disease it spawns, but most importantly she’s learned how much further science has to go in understanding Cocci and Valley fever.

Barker’s research

Barker got into Valley fever almost by accident; her husband was accepted into a graduate program at U of A; she looked for a job there and found an opening in a biosafety level (BSL) 3 lab. It would give her skills she’d likely need in future labs and an opportunity to work with interesting organisms.

Her interest in Cocci grew as she worked with it, but she picked that fungus for a more personal reason as well: both her husband and her dog suffered severe cases of Valley fever while they lived in Tucson, and unbeknownst to her she picked up the fungus as well. Her husband recovered fully; her dog had a relapse but eventually recovered. Regardless, she’d found her passion.

Even after all these years, though, it remains a tricky disease. Earlier studies showed about 60 percent of infected people showed no symptoms and had no idea they were infected; Barker said the scientific community still feels comfortable with those numbers. The majority of those remaining can get quite sick with pneumonia or severe flulike symptoms but eventually fully recover. Some were correctly diagnosed and treated with antifungal medication; others simply fought it off over time.

But a few people get sick and keep getting sicker, sometimes fighting the illness for months at a time. They’re frequently misdiagnosed and sent home with antibiotics or antiviral medication, which in the best cases were ineffective and in the worst cases made the illness worse. One man, the subject of a journal article Barker recently reviewed, was in and out of doctor’s offices for a year with a variety of symptoms. By the time he was correctly diagnosed, the fungus had overwhelmed his body and he died soon after.

“He had it everywhere,” she said. “He had it in his lungs, his spleen, his GI tract. It was awful.”

Everything Barker knows about Cocci and Valley fever leads her to four possible conclusions: some feature about the fungus itself influences severity of the illness (different strains of Cocci, exposure to more spores); some host factor dictates severity (weakened immune system, genetic background); the amount of exposure from the environmental (how many spores a person breathes in); or some combination of the three. Her research centers around those possible outcomes.

“The big, overarching question that drives pretty much everything in my lab is what explains the variation in disease,” Barker said. “Why do some people get really, really sick and other people seem to have no symptoms?”

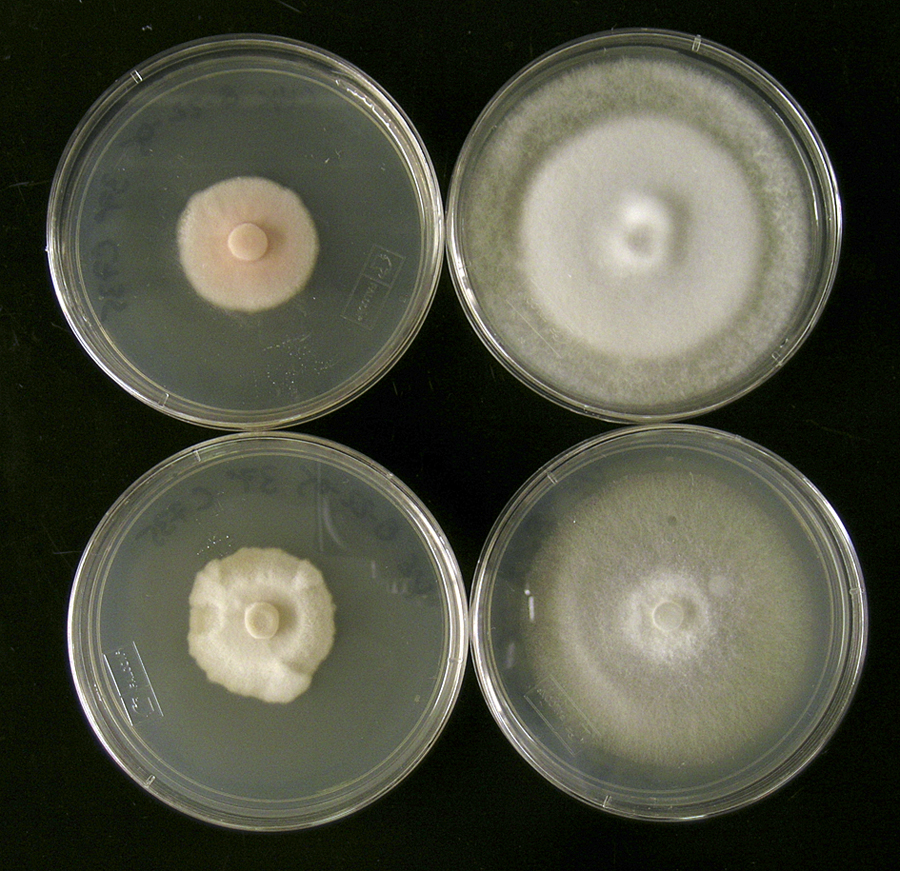

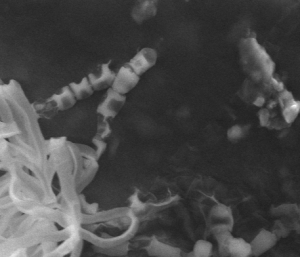

Right now in her lab she’s putting fungus and immune cells together to see how they react, which could explain why mammalian lung tissue responds to Cocci the way it does: white blood cells rushing to the fungus in attempt to kill it, but dying themselves because the fungal cell is too large or toxic. In a healthy response, this eventually works enough to create a self-contained nodule. When the body doesn’t respond appropriately, though, surrounding tissue starts dying.

Other research includes examining host cells and fungal cells to see if there are different variations of the fungus, missing genes in host cells or some clue that could explain the disparity in Valley fever responses.

She also wants to look at where Cocci originates in nature, which requires collecting DNA from dust and soil samples to see if the fungus is present. To do this she and her team will have to collect thousands of samples, preferably from the same 100 or so sites once a month for a year or more. That could tell her if the fungus is more likely to be present in certain seasons or in wetter, dryer, hotter or windier times of the year.

What we know about Valley fever

Where it’s found

Valley fever is named after the San Joaquin Valley in California, but Cocci was discovered in the late 1800s in Argentina. It’s found throughout North, Central and South America but nowhere outside the New World. The large majority of reports of either the fungus or Valley fever are in the Sonoran Desert, which includes a sizable chunk of southern Arizona.

Who’s affected

Research shows all mammals are susceptible. Humans and dogs are the most frequent victims, but scientists have found it in wolves and even dolphins. There have been a few instances of Valley fever in reptiles, but Barker said those were zoo animals, which tend to experience higher stress than animals in the wild, so it was difficult to draw a larger conclusion.

Some causes of the variation in severity

Scientists can’t fully explain the variation in disease, but they have found some culprits, Barker said. The number of spores a person is exposed to affects the severity of illness. In a lab, mice could shake off exposure to 10 spores but got sicker for longer when exposed to 100 spores. Mice exposed to 1,000 spores died, almost without exception.

People with compromised immune systems also are likelier to get sicker from Valley fever as with most infectious diseases, Barker said. For example, cancer and transplant patients whose immune symptoms have been suppressed to help them fight the initial diseases often can’t mount the immune response needed.

Some knowledge of its history

Pockets of the fungus found out in nature have been connected to dead and decaying animals below the surface, Barker said. Scientists have found some connections with a group of rodents, although they can’t draw that conclusion with certainty.

What we don’t know about Valley fever

Why people are affected the way they are

“In a very small percentage of people, it just overwhelms their immune system, or maybe they inhaled a lot of the fungal spores,” Barker said. “We just don’t really understand why.”

What effect a changing climate may have on the fungus

“That’s what’s actually fascinated me about this organism,” Barker said. “Why is it only in the New World? Why is it so concentrated in the Sonoran Desert? What is its natural host? What does it associate with in the environment? What is it doing in the environment?”

That last question is especially fraught. Since scientists don’t know how the fungus interacts with other parts of the environment, they don’t know how factors like climate change will affect how it behaves. It is possible that as the Earth’s temperature rises, climates will dry out and the fungus will be able to grow in places it previously couldn’t inhabit.

“We want to know if certain areas, certain environments and certain times of the year correlate to higher rates,” she said. “That’s the most direct public health mediation we could do, actually figuring out if there really is something in the environment.”

How much future risk the disease presents

Barker didn’t get sick the first time she was exposed to Valley fever. Decades from now, however, when age takes its natural toll on her immune system, she has no idea what the dormant nodule may do.

“It’s something we don’t know,” she said. “It’s something we have not looked at.”

How to efficiently diagnose it

Valley fever takes an average of four doctor’s visits to diagnose, Barker said. That’s potentially a month or more of feeling lethargic, under the weather and getting unnecessary treatments for diseases the patient doesn’t have. It’s also several weeks of the fungus continuing to grow and possibly moving into other parts of the body, like the joints.

The research community has created a quicker, more effective diagnostic tool for Valley fever, which looks at DNA present in sputum of lavage fluid, but it is not yet clinically available. However, because the symptoms of the disease are similar to the flu, it’s rare for Valley fever to be a consideration, particularly outside of Arizona.

How to treat or prevent it

Antibiotics do not work. Antifungals may—their effectiveness is still being tested—but even antifungals don’t wipe the disease from the host’s body. The medication forces the fungus into dormancy, created nodules like the one Barker’s doctor found in her lung.

Some infected individuals have to take antifungals for the rest of their lives to keep the fungus under control, while others don’t. Barker said that dependency has cropped up as she’s worked with dogs and rehabilitating Mexican grey wolves at the Southwest Wildlife Conservation Center in North Scottsdale.

“If you do suspect Valley fever, get your dog to the vet and you get to the doctor and ask for the test,” Barker said.