By Heidi Toth

NAU Communications

Writing forced Annette McGivney to face her deepest trauma, sending her spiraling into darkness. Then it gave her the tools to heal.

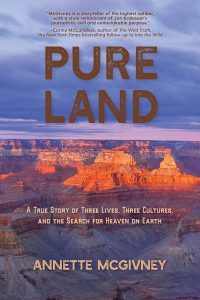

McGivney, a principal lecturer of journalism at Northern Arizona University, just published her fifth book: “Pure Land: A True Story of Three Lives, Three Cultures and the Search for Heaven on Earth.” She spent a decade investigating the book, which took her from the site of a brutal murder in the Grand Canyon to Japan and, unexpectedly, into the deep secrets of her past, finishing with a book much different from the one she planned to write when she started.

For the National Day of Writing on Oct. 20, McGivney talked with NAU News about her complicated journey writing the book, why she chose this story and why people should write.

What is your background in writing?

I always loved to write, and it seemed like the one thing that I was actually good at, so I was always pushed in that direction. I was an editor at my high school newspaper, and I got my degree in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin.

Journalism seemed like a good way to make a living as a writer. I graduated from college in 1983 and immediately began freelance writing for different magazines. I was an editor of a city magazine, and I started my own magazine called Texas Life a couple years out of college.

Then in 1990 I became an editor at Backpacker magazine. I have been writing for Backpacker for many years, and I’ve also written for other outdoor publications like Outside and Arizona Highways. I joined NAU as full-time faculty member in 2004. I had spent lot of my career as a journalist and a writer, so teaching journalism seemed like an outgrowth of that. But I never really slowed down in terms of my writing productivity while teaching at NAU.

The way I process things in my own life is through writing, and my preferred mode of communication with the world is words and writing.

How did you come across this story?

Because I am the southwest editor for Backpacker, I pay attention to what’s going on in Grand Canyon, including land management, hiking trails and bad things that happen to people in the canyon. When I first saw this story on the front page of the Daily Sun, the headline said something like, “Japanese hiker missing in Supai in Grand Canyon,” and I started following it. Four days later, there was the headline, “Body found presumed to be that of Japanese hiker.”

That piqued my curiosity about the story. There have been murders before in Grand Canyon, but they’re usually relationship-related. Presumably this person was killed by a stranger and stabbed 29 times. There were just so many questions that I proposed to Backpacker that I do a story.

I went down to Supai in January 2007. It was challenging because the tribal council of the Havasupai tribe had banned media from the reservation; they didn’t want any more publicity about the murder, given the sensational nature of crime. I managed to get down there and did some covert reporting. The FBI was investigating the case, and they couldn’t give me much information because they didn’t want to give away what they needed to present at trial.

It was mostly me piecing things together on my own, trying to connect the dots around what might have happened to the victim, Tomomi Hamamure, what was going on with the kid who killed her, an 18-year-old Havasupai boy, and what his history was.

The person who murdered Tomomi was Randy Wescogame. He spent a lot of time in juvenile corrections, and when he was living in Supai, he got into a lot of trouble and had problems in school. Randy’s father, Billy, gave me a lot of Randy’s school records, and I was able to piece things together about his history. The story was published in Backpacker in June 2007.

That was supposed to be it for me, so I moved on to other things. I worked on another book, but I just could not stop thinking about the whole thing. There was so much more I still wanted to know, and I especially wanted to know more about Tomomi. Her family would not talk to media in Japan or in the United States, so there were absolutely zero clues about why she went hiking there, what her connection was to Grand Canyon and what her life was like in Japan.

Almost every day I wondered, and that’s how it started. That curiosity built into a book.

What was your process in writing this book?

It was so difficult. If you count the time I started working on the magazine article, this book took 10 years. Ten years. During that time, I was a single parent raising a son, taking care of two parents with Alzheimer’s and working full-time at NAU. But I was just so in love with this story. I shared it with friends, and they’d tell me, “You have really got something here. Don’t give up.”

I first did a proposal of the book, where it was just going to be about Tomomi and Randy. I had an agent in New York who circulated that proposal. It happened to be at a time when the book publishing business was going through a lot of economic disruption, so there was hesitation and I just wasn’t able to find a publisher through the traditional process.

Another factor is in 2009, after trying repeatedly, I was able to connect with Tomomi’s family in Japan. They invited me to come to Japan, so I took my son and the Japanese interpreter who worked on the case for the FBI, and the three of us went to Japan. I drained my savings to do this; it’s not like I had a big book advance. I was doing it because I was on a mission.

Being in Japan and getting to know Tomomi’s family— I said I want to write a story that honors Tomomi’s life, so she’s not known by how she died but how she lived. I made a promise to her father that I would do this.

So when publishers didn’t accept the first proposal, I couldn’t just say, “I guess I’ll move onto something else.” I made a promise to Tomomi’s father and to myself, and I believed so strongly in this story that I had to share it.

After the first proposal didn’t find a publisher, I continued to research. By then Randy had been sentenced and put in prison, so a couple years after the murder, the FBI and the Coconino County Sheriff’s Office turned over all their files to me.

As I dug into the nitty-gritty of the investigation, including audio of the confession from Randy where he described in his own words what he did, it started to really affect me psychologically. Not only learning all the stuff about Randy, but also my connection to Tomomi and the deep sadness and pain that was unloaded from her family and friends when I was in Japan.

Journalists think of themselves as impervious, including me. You sort of shut down and just do the job. But the violence and the sadness started getting to me. I thought it was all about Randy and Tomomi, but it turned out it was chipping away at my own psyche. I had a pretty troubled childhood in a dysfunctional home, and that bubbled up to the surface.

I kept trying to shut it down, but eventually with all the factors of my life—my parents, and my marriage that was falling apart and then this book—I had an emotional crisis, and I set the book aside for a year or two while I worked on myself.

When I came back to the book, I realized I had become part of the story. It wasn’t just about the investigation into Tomomi’s and Randy’s lives, it was about how my investigation pulled me in. It was about the things the three of us endured as children and the connection to the natural world that Tomomi shared in her diary. I was able to see in every aspect of her life, how much she loved the natural world, and especially western wilderness, and that was my connection too.

I was able to find my way out of this dark tunnel to the light by focusing on what got Tomomi through her hard times, and that got me through too, just spending time in Grand Canyon and other wild places. So that became part of the book too.

So the book made you face the darkness but also provided the way out?

So the book made you face the darkness but also provided the way out?

It is like a big, crazy, complicated book! And not in an academic way either.

It’s not a self-help book and I don’t get into a lot of psychology, but there is a little bit of psychology in the book. Sigmund Freud came up with this term during his research, repetition compulsion, which is when people, especially people who have repressed memories from childhood that were so terrible, or so unacknowledged, that they couldn’t work through it during the time, basically had to lock it away in a safe in their mind.

As adults, they had these memories that they’re consciously not aware of, but subconsciously those memories are wreaking havoc on them and causing them to feel a sense of uneasiness or that something is wrong and they don’t know what it is. To try and figure that out, lots of times they subconsciously choose situations that are repeating the circumstances of the original trauma.

What I was doing, as I began investigating my own psychology, was I was trying to figure out why Randy killed Tomomi because when I was a child my father beat me really violently, almost on a daily basis, and I think—and I’m not a psychiatrist, but this is my interpretation—I was trying to figure out why he did it because ultimately I was trying to figure out why my father beat me, because that little kid with those repressed memories thought, if I can figure out why my dad is doing this, then I can make it stop.

That was the drive behind going into that dark space. I wasn’t reliving the murder, I was actually reliving my own childhood, and that was the most terrifying experience I ever had—having those memories of childhood explode back into my mind and my body. It was full-blown PTSD. It was terrifying, but ultimately, writing and nature have been the things that helped me get through life.

Working on this story, I just kept at it and it helped me to work through my own trauma.

What advice would you give would-be writers?

This book is such an unusual story, the big publishers said, “This is a really amazing story, but our marketing department says they can’t handle it. It doesn’t fit into the true crime genre, it doesn’t fit into the memoir genre. We don’t know how to market this book, so we can’t take it.”

But I was so invested in the story and keeping my promise and making sure I was able to tell the story the way it needed to be told, keeping true to the facts and not having a marketing department try and change things to make it more commercial that I feel like ultimately, I just did the story my way and finally found a publisher on my own that didn’t blink once when they saw the story. I didn’t have to wrestle with them on anything.

I’d tell writers that when you believe in your heart that this is the way a story needs to be told, just stick with that and don’t let commercial forces convince you otherwise. Ultimately people want something that’s authentic and heartfelt and shakes things up. That’s what makes a book or story something that people remember forever, even though it makes marketing people nervous.

We just can’t let commercial interests drive the creative process.

What advice would you give people who don’t think of themselves as writers?

Writing is like running. You don’t have to love it. (laughing) But I do feel like language is our first, earliest form of communication, and the next form we learn as children is reading and writing. I feel like writing is a very integral part of how we transfer our thoughts to others and how we can process our own thoughts.

A great thing about writing is once you’ve written it down you can go back and revisit it. I would encourage people who think, “Oh, I’m not a good writer” to know everyone can write.

Writing your thoughts in a journal just for yourself is a gift; it’s one way to have the healthy practice of checking in emotionally and mentally. It doesn’t have to be just writing. Some people like to just doodle and draw pictures. It’s about putting your feelings and thoughts on paper.

Writing is a creative process, just like painting and photography and others. I have found that being outdoors, especially in the wilderness and beautiful places like Grand Canyon, really stimulates the creative process. Even if people don’t view themselves as a writer in their everyday life, I would encourage people to go on hikes and go camping and take a journal and see what it feels like when you’re out in nature to write.

It sort of unleashes creativity. Your brain in your everyday life is saying you can’t do this, but in nature, everything is possible.