By Carly Banks

NAU Communications

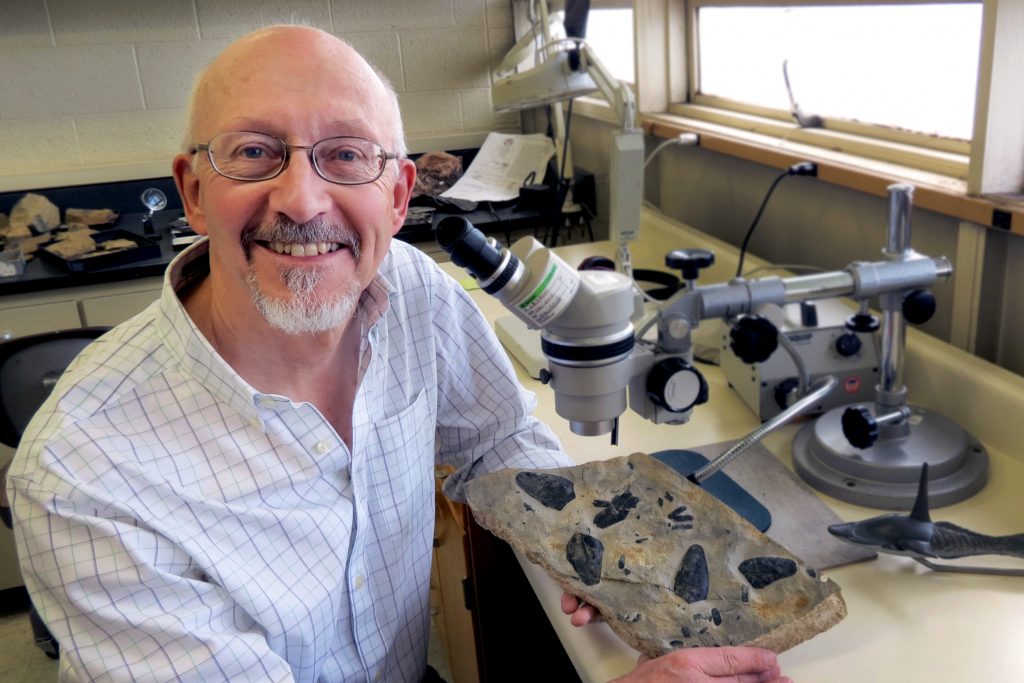

Paleontologist David Elliott will often analyze a collection of fossilized bone for years, if not decades before additional examples come along.

As someone who studies a primitive group of fish that became extinct more than 358 million years ago, it’s safe to assume that new fossil specimens don’t show up very often.

In the summer of 1995, however, after more than a decade since the last specimens were collected in the Arctic, a group of structural geologists mapping Death Valley stumbled upon some small fragments of fossilized bone preserved in rock sediments. Unbeknownst to them, those bones belonged to the long extinct heterostracan fish, the exact group Elliott studies.

A professor at Northern Arizona University, Elliott has examined fish fossils for more than 40 years and looks forward to the occasional days when new fossil specimens find their way to him.

“When the material was initially sent to me, I was very excited because it added a new site to the ones we had been looking at along western North America and this was the most southerly one.”

After applying for a permit from the National Park Service to search for, collect and study the early heterostracan fossils, Elliott led a group of students to the park in hopes of finding more.

“I spent three years collecting at Death Valley,” he said. “We collected a couple of cabinets full of material—difficult to say how much that is, but it was a lot! Of course, that was very much trimmed down as we prepared the specimens.”

Most of the fossil fragments were familiar, comparable to assemblages of early vertebrates preserved in similar channel fills in Utah, Idaho and Nevada. The new fossils made it possible to correlate the Death Valley fossil localities with other localities across the western U.S.

But one piece collected was the first of its kind—a full lower mouth plate.

“We describe lots of species. We can piece together structures and fit them into an evolutionary succession based on computer analysis. But to me, often, the interesting thing is the animal itself. What was it like? What was it doing? How was it feeding?”

Until this point, little was known about this fish. Looking at the bony armored plates that covered the majority of its body, it’s safe to assume it was active, but that can’t be known for sure.

After nearly 20 years of study, this lower mouth plate was added to the puzzle, and proved to be especially interesting because these Paleozoic fish were jawless.

Today, the only modern examples of jawless vertebrates are lamprey and hagfish, and according to Elliott, they are rather disgusting creatures. Unlike the heterostracans, these fish are parasitic organisms that attach to hosts to feed on them, making comparisons with the fossils useless. Instead, this lower mouth plate provided questions to answers Elliott had long been asking—what are these fish really like?

“This single plate gives us some idea of what was going on in the mouth. It suggests that the fish dropped their lower plate, grazed along the bottom of algal beds and took in smaller organisms as they filtered through the water.”

Elliott continues to analyze these fossil fragments as well as others he’s collected throughout the decades from the Canadian Arctic Islands, western North America, western Russia and the Baltic states.

He is well aware that to most, fish fossils are not nearly as interesting as dinosaur bones. But for the first year, the National Park Service will honor National Fossil Day on Oct. 11 with a depiction of an extinct fish instead of a dinosaur, and not just any fish—Elliott’s heterostracan.

“I was pleased when the Park Service selected me for National Fossil Day. It’s a personal honor, of course, but it also gives some coverage to a group of organisms that are not often in the limelight.”

The National Park Service first established the annual celebration to promote the scientific and educational values of fossils. So instead of stopping at the Grand Canyon, staring out at the landscape for a measly 30 seconds, then hopping back in the car to leave, this day was created to help inform people that national parks are more than a pretty view.

“If you don’t know anything about all of this, you stand there and look, say ‘that’s neat,’ and walk away. You’d never know that you’re missing 2-billion-year-old geologic rock layers, 800-year-old Indian ruins and 358-million-year-old fish fossils.”